As a co-host of 5-4, a podcast about how much the Supreme Court sucks, Rhiannon Hamam spends an inordinate amount of time reading some of the most ghoulish, morally bankrupt gibberish that nine life-tenured fancy lawyers could ever come up with. This summer for Balls & Strikes, she’s returning to a dozen of the worst cases she’s been unable to get out of her head, despite her fondest wishes and best efforts, to see how all the awful shit the Court is doing today intersects with all the awful shit it’s done before. This is Wild Pitches, a column that will remind you that saying that the Court is “bad” right now does not mean that it was ever “good” in the first place.

Never one to shy away from siding with business interests, the Supreme Court has consistently ruled to limit the scope of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) when it inconveniences corporations. When Toyota Manufacturing fired Ella Williams rather than provide her with reasonable accommodations for her disability, the Court sided with the big vroom vroom company in yet another assembly-line ruling tamping down on the protections of anti-discrimination statutes.

The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed by Congress in 1991 and prohibits discrimination against people with disability in employment, public accommodations, transportation, and other areas of public life. Like the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made employment discrimination on the basis of race (among many other things) illegal, the ADA ensures that people cannot be discriminated against in employment on the basis of disability. In addition to workplace protections, the ADA requires employers with 15 or more employees to provide “reasonable accommodations” to workers with disabilities. These accommodations can include job reconfiguration, assistive devices, transfers, schedule changes, and more.

The purpose of the law was to address widespread workplace discrimination against people with disabilities. Studies considered by Congress when drafting the ADA showed that disabled people were the most economically disadvantaged minority group in the United States. In short, the ADA was passed to remedy profound systemic inequities, and was born out of the foundational idea that people with disabilities are qualified and able to work, and that stereotypes indicating otherwise perpetuate economic dependency and poverty (which is itself a cause of disability). But since the ADA’s enactment, employers have fought against their obligations under the law, citing cost and employee “morale” (complaints from non-disabled workers about accommodations given to disabled workers–or, put another way, another form of workplace discrimination against disabled people).

Ella Williams began working for Toyota at the company’s Kentucky manufacturing plant in August 1990. She was assigned to work on the engine fabrication assembly line, where she had to use pneumatic tools which, powered by compressed air, can involve intense vibrations for the handler. Williams developed severe pain in her upper body, and a company-provided physician diagnosed her with carpal tunnel syndrome and tendonitis in her hands, wrists, and arms. As a result, she recalled that “I got lumps the size of a hen’s egg in my wrists, and my hands and fingers got curled up like animal claws.” A doctor ordered Williams not to perform overhead work, engage in repetitive flexion or extension of her arms, or use vibratory or pneumatic tools.

Toyota provided modified work duties to Williams, and eventually placed her on a quality control team in December 1993, where workers inspected the cars’ paint jobs and exterior surfaces. Williams was able to perform the job duties required in that role, but in the fall of 1996, Toyota enacted a new policy that required the inspection team members to also audit the shell body of the cars, which entailed wiping each car with oil and inspecting it for flaws. For this task, Williams was required “to hold her hands and arms up around shoulder height for several hours at a time.”

Williams’s pain in her upper body returned. She visited Toyota’s in-house medical service provider again, and was diagnosed with tendonitis around her shoulder blades and forearms, and nerve compression and irritation which caused nerve pain in her upper body. Williams requested that Toyota accommodate her disability by allowing her to return to her original inspection team duties, without the shell body audit. She said her request was refused and she suffered further injuries on the job. Williams was fired in January 1997; Toyota claimed that her employment was terminated because she stopped showing up to work.

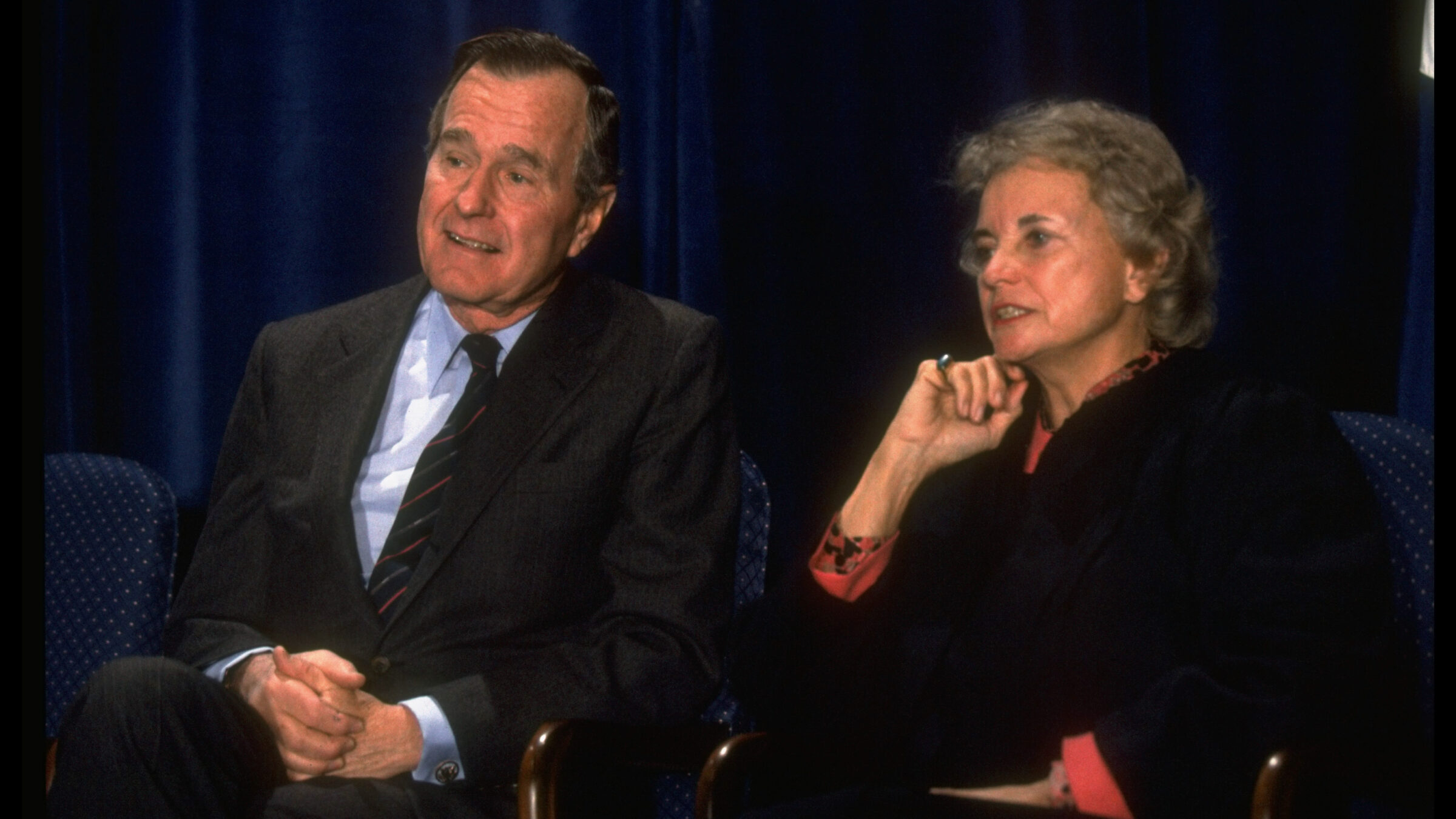

Photo by Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images

Ella Williams sued Toyota (which was represented at the Supreme Court by now-Chief Justice John Roberts), arguing that the company had failed to provide her with reasonable accommodations for her disability. But in a unanimous decision delivered by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in 2002, the Supreme Court ignored the accommodations Williams was owed, instead ruling that she wasn’t even disabled. Under the law, the opinion stated, a disability must be a condition that “substantially limits” a “major life activity.” Adding that the impairment must be “permanent or long term,” O’Connor asserted that in order to show that a person is disabled, they must show that they are prevented or restricted from “doing activities that are of central importance to most people’s daily lives.” Of course, Williams had shown that her condition substantially limited her in manual tasks, housework, gardening, playing with her children, lifting, and working. But the Court tossed all of that aside, indicating instead that activities of “central importance” to daily life are much more narrow, like “walking, seeing, [and] hearing.” In the Supreme Court’s estimation, Ella Williams may have had debilitating carpal tunnel, tendonitis, and nerve damage (caused by her job, no less!) that prevented her from doing the Toyota job, but she could still walk, see, and hear–so maybe she could just find another job somewhere else. Though the ADA was intended to prohibit employers from discriminating against people with disabilities when reasonable accommodations can be made to allow them to do their jobs, the Court read the law to say that those protections only applied to an extremely narrowly-defined class of disabled people, for whom impairments cause near-total loss of central physical functioning (as identified by nine justices who never worked a factory assembly line in their lives).

The case and its progeny were so awful that Congress passed amendments to the ADA in 2008 to override the rulings. The ADA Amendments Act explicitly identifies Toyota Manufacturing v. Williams as one of a series of Supreme Court cases that led to courts “[finding] in individual cases that people with a range of substantially limiting impairments are not people with disabilities.” The definition of the term “disability” was also changed in the law, this time with the mandate that disability should be construed in favor of “broad coverage of individuals to the maximum extent permitted by the terms of the ADA and generally shall not require extensive analysis.” No more of this semantic bending and twisting to decide that discrimination on the basis of disability doesn’t count unless the Supreme Court thinks you’re disabled–civil rights extend to people with all sorts of disabilities that impact their lives and work in myriad ways.

Though Congress acted to rectify the Supreme Court’s reckless disregard for discrimination against people with disabilities, Toyota Manufacturing v. Williams exemplifies the conservative legal movement’s penchant for judicial activism targeted at gutting civil rights protections in the law. Here, the nine-person council of decidedly non-experts on disability created their own definition of the term, excluding untold thousands from coverage of the ADA in the ensuing years before the Amendments Act. On the one hand, conservatives deride “judicial activism” that supposedly allows judges to insert their own policy preferences into answering legal questions–but when they do their own judicial activism in service of relegating people to a permanent underclass status, to damaging stigma and stereotype, and to economic violence, that’s merely statutory construction. Personally, I’m sick of the whole schtick.

Photo by Diana Walker/Getty Images

Something else nags at me about this case: just how out of touch the Supreme Court is. O’Connor remarks in the opinion that carpal tunnel syndrome can dissipate over time, as if Ella Williams maybe not having carpal tunnel syndrome at some unknown point in the future means she didn’t have a disability while working for Toyota. O’Connor brushes away the host of physical activities Williams struggled with–including sweeping, dressing herself unassisted, and driving long distances, in addition to gardening and playing with her children–as a result of her disability, saying that since Williams could brush her teeth and fix breakfast, it just doesn’t rise to the level of what they think disability is. Millions of people who have worked in a factory, in construction or manual labor, in retail or restaurants, in offices or outside, so many of the regular jobs that regular people do every day, understand intuitively through experience how a disability could lead to discrimination in the workplace, and how important the law is requiring bosses to accommodate for a disability so that people can do their jobs and do them well. Nine judges who read and write (oftentimes pretty poorly) for a living, with premium health insurance and six-figure salaries (in addition to all the free luxury vacations) clearly do not understand what disability discrimination means to working people. Sorry, but Supreme Court justice is a fake job.

My proposal: Supreme Court justices are replaced with a primary school teacher nearing retirement, a manufacturing assembly line worker who supports their family, and a 19-year-old Forever 21 employee who mans the fitting rooms. Promise they’ll do a better job.