In a sharply-divided Supreme Court controlled by a conservative supermajority, the unanimous outcome in this term’s first opinion, Arellano v. McDonough, may seem surprising. While serving in the Navy, Adolfo Arellano was on an aircraft carrier that collided with another ship in 1980. He was nearly swept overboard, and witnessed the injuries and deaths of several of his comrades. As a result, he developed severe mental health conditions, which caused him to miss the deadline to apply for disability benefits. Although Arellano applied for and began receiving benefits in 2011, he first went some three decades without getting the help to which he was entitled.

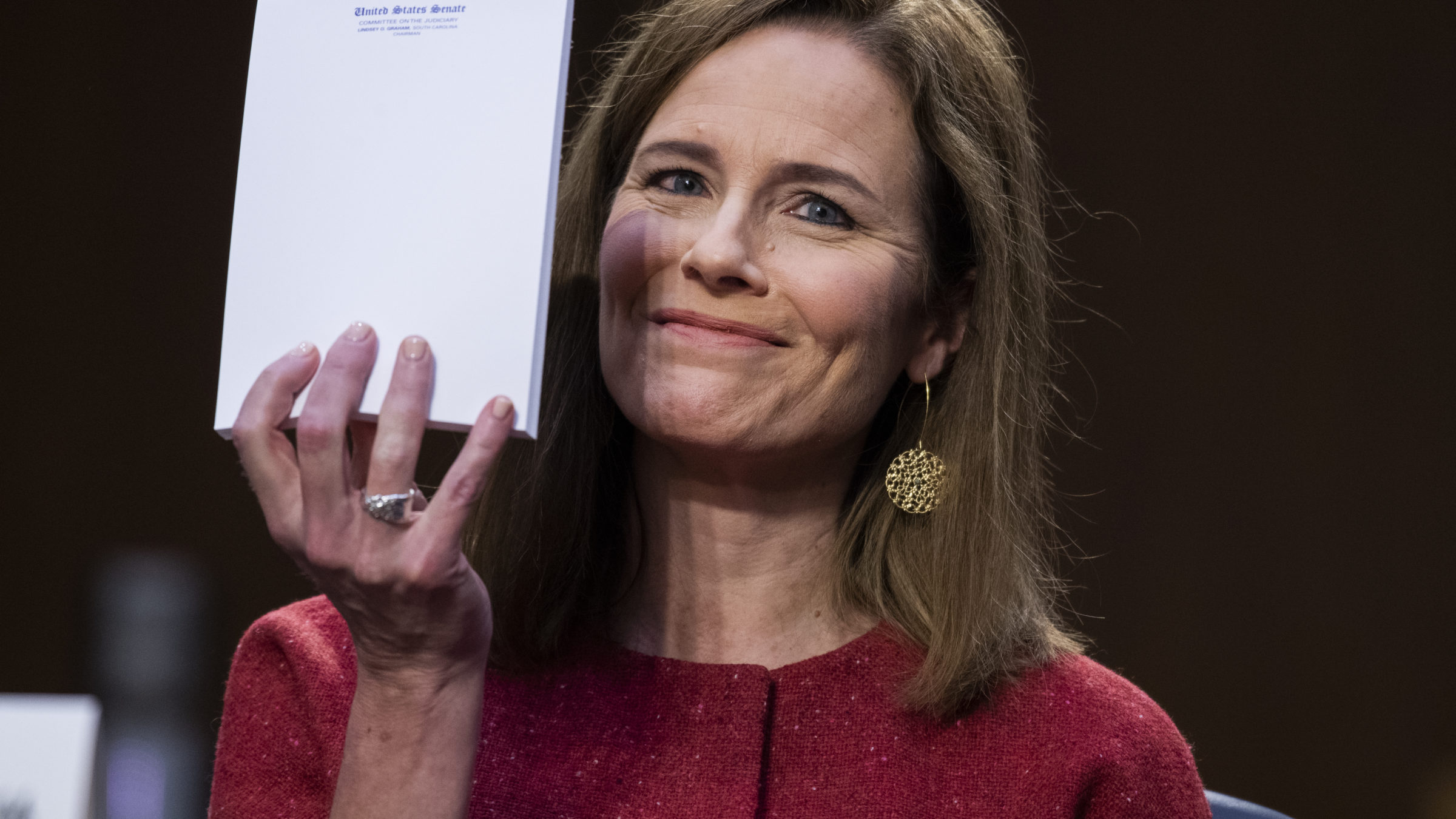

Yet in a 9-0 opinion by written by Justice Amy Coney Barrett and published late last month, the Court relied on a hyper-rigid textual analysis of the veterans’ disability statutes to conclude that Arellano is not entitled to equitable tolling—a legal concept that would excuse the delay and allow him to establish an earlier effective date of his disability. Although Arellano has been “100% disabled” since the Carter administration, the Court denied his suffering and withheld the compensation that may have helped make him whole.

Why did the Court’s liberals, who usually fight to protect the rights of vulnerable individuals against the bulldozer of the conservative majority, join an opinion using formalist logic to deprive a disabled veteran of benefits? It’s simple: Courts—not only Supreme Court justices, but also the federal district and appeals court judges below them—have a long history of caring more about making the rules simpler for the VA than about supporting suffering veterans.

When you have to make a list of the reasons you care about veterans (Photo by Tom Williams-Pool/Getty Images)

Most veterans can receive significant government benefits meant to compensate them and ease their transitions from the military, but they can be hard to access. Disabled veterans are entitled to tax-free, monthly payments for the duration of symptoms of injuries connected to military service. However, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (VA) disability application process can be extremely difficult for veterans to navigate, and when veterans make a mistake or disagree with the VA’s decision, different procedures and legal principles apply to veterans’ law than to other public benefits.

A major reason why the law surrounding veterans’ benefits can be so exacting may be that the VA acts almost as the judge and the veteran’s case worker The VA is required to help veterans develop their disability claims by collecting records, setting up doctor’s exams, and more. In theory, in an ostensibly claimant-friendly system like this one, it is reasonable to impose stricter appeals and filing deadlines than those employed by other government benefits systems. In practice, when things don’t go according to plan, disabled veterans are left to navigate the VA bureaucracy without a safety net.

Another problem is that the VA only knows what the veteran knows to share with them. If veterans, like Arellano, have disabilities that keep them from applying for benefits in the first place, or from disclosing certain symptoms, it doesn’t matter how (allegedly) supportive the system is. Poorly-developed applications in disability cases are a particular problem for veterans because there is no district court where an attorney can develop a record to preserve issues for appeal. (The disability application and internal VA records can approximate a record, but only about 18 percent of veterans have representation at that stage.) As a result, even if veterans are represented in their appeals, their attorneys start the process on their heels.

In fairness to the courts, the law here is skewed not in favor of disabled veterans, but of the government’s checkbook. One might expect that the effective date of a veteran’s disability would match the date the disability started. After all, other disability programs like SSDI expend significant effort identifying the date of onset of disabilities as the effective date. However, veterans’ disability payments typically don’t start earlier than the date of the application, even if the person has been disabled for decades.

In cases like Adolfo Arellano’s, where the disability interfered with a veteran’s ability to file, courts could apply principles like equitable tolling, extending statutory deadlines with which applicants weren’t able to comply. Again, this is standard practice in SSDI cases, where applicants who miss deadlines because of a disability get some flexibility in the interest of justice. Veterans, however, are out of luck.

Even cases where the VA’s own actions caused veterans to miss their deadlines, courts have relied on narrow readings of the law to deny claims. In Butler v. Shinseki, a 2010 Federal Circuit case, the VA incorrectly told a veteran that he was ineligible for disability benefits due to an unjust less-than-honorable discharge that the military later corrected. This advice directly from the VA kept the veteran from applying for disability until after the one-year window, but the court refused to toll the deadline. In George v. McDonough—another recent Amy Coney Barrett banger—the VA applied an incorrect interpretation of an unambiguous statute to deny a veteran benefits. The Court, however, refused to allow the veteran an earlier effective date corresponding to his original denied claim.

Pictured: the majority in Arellano (Photo by Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

In an especially egregious recent case, Taylor v. McDonough, a veteran volunteered for a chemical weapons testing program that exposed him to nerve agents that caused permanent disabilities. The government threatened him with prosecution if he revealed his experience, which prevented him from applying for disability benefits. A panel of the Federal Circuit applied equitable estoppel—a legal principle used to prevent parties who acted unfairly from obtaining a judgment in their favor—to keep the VA from denying the veteran an earlier effective claim date. However, the full Federal Circuit stayed the ruling, and now seems poised to reverse in the wake of Arellano.

Who is going to protect veterans from the VA’s bottom line if not the courts? Even Justice Antonin Scalia, who loved to squash marginalized people with technicalities, once said that in veterans’ benefits cases, interpretive doubt must be resolved in favor of veterans. (This status should not be a mere “thumb on the scale,” he said, but “more like a fist than a thumb.”) In each of these cases, a web of legalese and abstractions obscures the reality that the veterans involved had been suffering from their injuries for years, abandoned by the government that caused them. They are the product of a Supreme Court that has shown again and again that it simply does not care about doing justice.

In this way, the courts are no different than politicians when it comes to veterans: They will pay lip service to the sacrifices veterans make, but when it comes down to it, “practical” considerations almost always carry the day. All of this is great news for the VA’s budget, but it leaves veterans as hidden collateral damage of war, left to struggle alone.