When Lindsay Hecox graduated from high school in 2019, she came out as transgender. A few months later, she started medically prescribed hormone replacement treatment—taking estrogen and suppressing testosterone—and enrolled at Boise State University, in part because she loved the running trails around campus. Hecox planned to try out for the women’s track and cross-country teams after she completed a year of hormone therapy, per National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) rules.

But in March 2020, when Hecox had fewer than five months of hormone therapy remaining before she could be NCAA-eligible, Idaho Republicans passed House Bill 500, the first state law in the country to ban trans women and girls from playing school sports on women’s and girls’ teams. Hecox filed a lawsuit a few weeks later, arguing that the statute violated her Fourteenth Amendment right to “equal protection of the laws” and asking a federal court to let her participate in women’s student athletics.

Idaho’s federal district court determined that Hecox was probably right, and issued a preliminary order in August 2020 that temporarily blocked the law from taking effect. As a result, Hecox was permitted to try out for track and cross-country for the fall semester, but didn’t make either team. Soon thereafter, she took a leave of absence from school so that she could work full-time and establish residency for in-state tuition purposes. When she re-enrolled at Boise State in 2022, Hecox joined the women’s club soccer team, and she planned to try out for the cross-country team again in 2023.

All the while, Hecox’s challenge to the constitutionality of House Bill 500 kept working its way through the federal court system. In June 2024, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals gave Idaho a major victory, vacating the district court’s preliminary order as it applied to people who weren’t involved in the case. In other words, the court continued to prevent Idaho from enforcing the law, but only against one person: Lindsay Hecox. Idaho, still hoping to vindicate the constitutionality of House Bill 500, appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Hecox started this lawsuit as a 19-year-old freshman in April 2020. Today, she’s 25, and as she gets ready to graduate in May, she’s had enough. “I am afraid that if I continue my lawsuit, I will personally be subjected to harassment that will negatively impact my mental health, my safety, and my ability to graduate as soon as possible,” she said in a declaration in September.

That month, Hecox filed a notice with the district court voluntarily dismissing her case with prejudice, meaning that she cannot bring the same claims again in the future. Under oath, she swore that she would not participate in any women’s sports covered by the Idaho law, thus giving the state “the precise relief that they would receive if they prevailed in this Court,” said her attorneys in another September filing.

There are rules about when federal courts, including the Supreme Court, can make a decision about a dispute. A big one is that there has to be a real dispute. Article III of the Constitution limits federal courts’ jurisdiction to actual cases or controversies; if the underlying issue has been resolved in some way, the case becomes moot, and courts are not supposed to decide it.

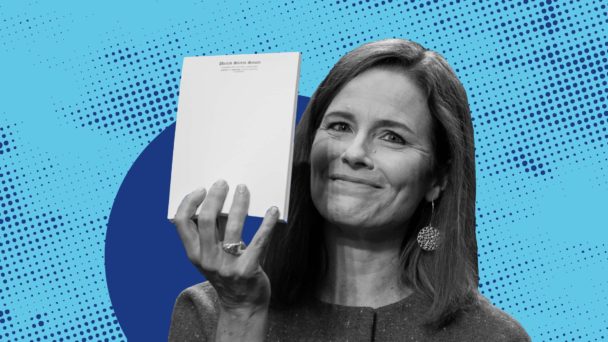

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Idaho, however, strenuously objected to Hecox’s dismissal. And back in October, the district court granted the state’s request to strike the dismissal from the record, concluding that “it would be fundamentally unfair to abandon the issue now on the eve of a final resolution.” Even though Hecox is out of sports and about to be out of school, on Tuesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in Little v. Hecox, because as the state all but acknowledges in its filings, it is after a different prize: “If Hecox is allowed to manufacture mootness,” they write, “then some of the most important cases the Court decides each Term will be placed in jeopardy while a plaintiff who won below weighs the risk of setting unfavorable nationwide precedent.”

Put simply, Idaho Republicans know Hecox’s case has no practical impact on their ability to enforce House Bill 500. What they want—and anticipate—is a ruling from the Court allowing legal discrimination against trans people from coast to coast.

To understand their expectation, one need only look at the Court’s membership. Three sitting justices dissented from Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 decision recognizing same-sex couples’ constitutional right to marry. Five justices, at minimum, allowed President Donald Trump to purge trans people from the military in United States v. Shilling, and six justices let states deny healthcare to trans children in United States v. Skrmetti. During the Skrmetti oral argument, Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett directly asked the advocates about the implications of the case for transgender athletes. And in concurring opinions in Skrmetti, Barrett, Justice Clarence Thomas, and Justice Samuel Alito all argued that trans people did not qualify as a suspect or quasi-suspect class under the Fourteenth Amendment, essentially concluding that the Constitution imposes no limits on anti-trans legislation.

The Court’s Republicans have already shown that they share Idaho Republicans’ hostility to the rights of LGBTQ people generally, and transgender people specifically. And they, too, recognize the case as an opportunity to do more damage to whatever remains of those rights.

Little v. Hecox is not about Lindsay Hecox. It’s not about sports. It’s about states’ power to discriminate against trans people. When Hecox dismissed her case, Idaho Republicans got what they said they wanted. But Republicans always want more, and they trust the Court to give it to them.