The Supreme Court issued a decision today in Alexander v. South Carolina Conference of the NAACP that reaffirmed its steadfast commitment to excluding Black people from the political process. In 2021, South Carolina’s Republican legislature created electoral maps that a federal court determined were racially discriminatory in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Today, the Supreme Court reversed that judgment, and created new hurdles for plaintiffs turning to the courts in search of protection from racial gerrymanders. To a greater extent than ever, the existence of voting rights will depend on the whims of unelected judges.

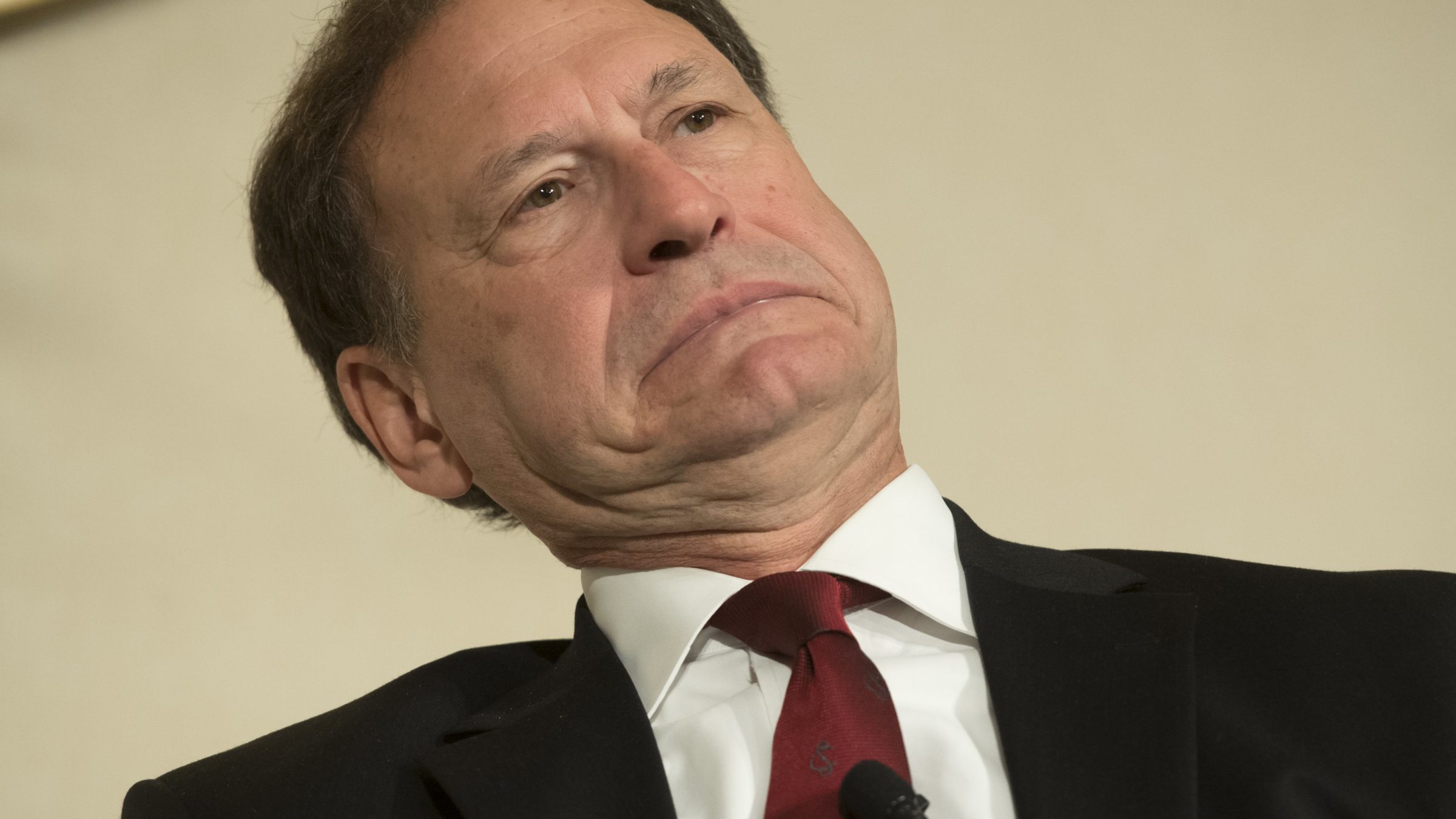

The majority opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito and joined by the five other conservative justices, comes right on the heels of New York Times reporting about the Alito household displaying flags in support of insurrectionists and Christian theocracy at his various residences. As it turns out, Alito is as committed to free and fair elections in his legal opinions as he is in his front yard(s). He has no respect for a multiracial democracy in which everyone can participate as equals, and is more than willing to use the levers of government as an instrument of that disrespect.

When Black people’s votes count the same as yours

At issue in this case is South Carolina’s first congressional district, which has historically been anchored by the city of Charleston. District 1 was solidly Republican for decades. But as the Black population in Charleston began to rise, Republicans’ grip on the district began to slip. Now, roughly a quarter of Charleston residents are Black. And analyses showed that District 1 would lean Democratic if it were between 21 and 24 percent Black, be a tossup at 20 percent, and lean Republican at 17 percent.

So, when the Republican legislature redrew the district after the 2020 Census, it kicked more than 30,000 Black Charlestonians out. Over 60 percent of District 1’s Black population were suddenly in District 6. And District 1’s Black population went back down to exactly 17 percent. This was, as a federal district court put it, “more than a coincidence,” and the court ordered the state to make a new, non-racist map.

The state appealed to the Supreme Court, and the lower court paused implementation of its order pending the Supreme Court’s decision, assuming the justices would resolve the case in advance of the April primaries. This assumption proved incorrect: In March of this year, with no Supreme Court ruling in sight, the lower court reluctantly allowed the map—a map that, again, a federal court had declared an illegal racial gerrymander—to go into effect for last month’s primaries.

The Court finally issued its ruling today, and it was not worth waiting for. Under existing precedent, racial gerrymandering is formally unconstitutional, but the Supreme Court decided a few years ago that partisan gerrymandering is not. And according to the Supreme Court today, the trial court made an error by not properly disentangling race from partisanship. “When partisanship and race correlate, it naturally follows that a map that has been gerrymandered to achieve a partisan end can look very similar to a racially gerrymandered map,” Alito writes. Basically, for the Court’s conservatives, it is A-OK to racially gerrymander as long as you are careful to call it something else.

At trial, the district court found that South Carolina maintained an impermissible racial target of 17 percent—again, the exact number at which District 1 leans Republican. Yet the Court chalked this up to coincidence, pointing out that the mapmaker denied the allegation and basically taking their word for it. The conservatives also discredited the lower court’s findings about the mass reassignment of Black voters, insisting that to prove a racial gerrymander, the challengers would need to present an alternative, non-gerrymandered map. According to Alito, they could have designed an alternative map “with ease,” and so their failure to submit one should be treated as an “implicit concession” of the weakness of their claims.

No such legal requirement existed before today. As recently as 2017, the Supreme Court expressly said in Cooper v. Harris that a plaintiff could win with or without an alternative map; as Justice Elena Kagan explained for the Cooper majority, “In no area of our equal protection law have we forced plaintiffs to submit one particular form of proof to prevail.” Alito argued bitterly in dissent in Cooper that “plaintiffs’ failure to produce an alternative map mandates reversal.” Now armed with a supermajority, Alito transformed his dissent into law. In Alexander, he wrote that map’s challengers “provided no direct evidence of a racial gerrymander, and their circumstantial evidence is very weak,” so they failed to prove that the “legislature subordinated traditional race-neutral districting principles…to racial considerations.”

Looking anew at the fact-finding of a trial court is not an appellate court’s job. And, as Justice Elena Kagan said in dissent, it gets worse: “The majority cannot begin to justify its ruling on the facts” without substantially changing the law “to impede racial-gerrymandering cases generally.” The opinion imposes a strict new “presumption of legislative good faith,” and warns that judges should not hastily accuse legislatures of engaging in “offensive and demeaning” conduct that resembles “political apartheid.” Perhaps most dangerously for future voting rights plaintiffs, Alito did not make clear just how much evidence it now takes to overcome this structural disadvantage. Going forward, the six conservatives are free to independently review lower court findings and pick and choose what evidence of gerrymandering is good enough, and what isn’t.

Throughout the opinion, Alito evinces an overriding concern about the possibility of a state action being called racist and no concern at all with the possibility of a state action being racist, leaving complainants of racial gerrymandering stranded without legal recourse. Alito has no need to fly coup-curious flags to signal his disdain for multiracial democracy. Opinions like this one make it abundantly clear.