Just before dropping the worst decision in decades on Monday, giving presidents a degree of unaccountability kings can only dream of, the Supreme Court released a decision in the NetChoice cases. These long-running Internet regulation cases concern the capacity of states—specifically, Texas and Florida—to dictate what speech Internet platforms must host without running afoul of the First Amendment. The core question: Does the First Amendment prevent Texas and Florida from mandating that Facebook and other social media companies keep up racist ravings, conspiracy theories, and misogynistic content? In a technically unanimous but dizzyingly convoluted ruling written by Justice Elena Kagan, the Supreme Court said: probably not.

A few years ago, Texas and Florida passed similar laws that purport to promote speech by limiting private platforms’ ability to “censor” their users. What most of us call content moderation—the common, necessary practice of platforms curating, deleting, and sorting speech—Texas and Florida characterized as left-wing Silicon Valley silencing of primarily conservative ideas. And though the First Amendment generally does not constrain private actors from regulating speech, Texas and Florida claimed that they could enact requirements that platforms not censor without running afoul of this principle.

Why? Because, in their view, states must ensure that each of their social media-addicted citizens who hate 5G and love hydroxychloroquine has access to Twitter. In a news release timed to the Texas law’s enactment, Governor Greg Abbott described “a dangerous movement by social media companies to silence conservative viewpoints and ideas.” Florida Governor Ron DeSantis seemed to imply that tech companies are run by soy boys, stating at the signing of Florida’s law that “the person… in pajamas on their laptop drinking a soy latte in Silicon Valley” is as much of a threat to speech as a “tyrant…in military fatigues.” Apparently Fidel Castro and Mark Zuckerberg have more in common than any of us ever realized.

When you won’t be president but still get to do reactionary politics (Photo by Paul Hennessy/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Both laws present obvious First Amendment problems. Generally, the First Amendment prevents the government from telling private entities how to order their own speech. This “editorial discretion” doctrine dates back over fifty years, originating in Miami Herald v. Tornillo, which struck down a Florida “right-of-reply” law for newspaper editorials. While the Court has not extended editorial discretion to every private entity that has since asserted it, the doctrine did seem to cover the choices of private groups with an expressive component to curate their speech. Social media companies, which set forth voluminous content moderation standards and make countless choices about what content to host or take down, seem paradigmatically covered by the First Amendment’s protection of editorial discretion.

NetChoice, a trade association of technology companies, quickly filed separate federal suits to challenge both laws, seeking preliminary injunctions. In the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, NetChoice largely prevailed in halting enforcement of the Florida law. But the Fifth Circuit ruled in favor of Texas, downplaying NetChoice’s First Amendment concerns, creating a circuit split. The Supreme Court granted review last fall. (I filed amicus briefs on behalf of groups of law professors in both the Eleventh Circuit and the Supreme Court.)

The delay on this opinion probably stems from the justices’ fixation at oral argument on a particular strategic move that NetChoice made: That it was worth it to argue that the Texas and Florida laws could almost never be constitutional, even beyond their application to NetChoice’s members. That bet made sense at the time, given the incoherence of the laws at issue.

But at oral argument, NetChoice faced tough questions from the bench regarding the propriety of a facial challenge in this case. While requiring Facebook to keep up objectionable content might violate that platform’s free expression rights, would the same rationale apply to, say, Uber? Does Uber’s business model seem sufficiently “expressive” to warrant editorial discretion protections? Given the range of technology platforms and the differences in their speech content, could NetChoice really claim that these laws’ unconstitutional applications to some specific platforms so substantially outweighed the constitutional ones?

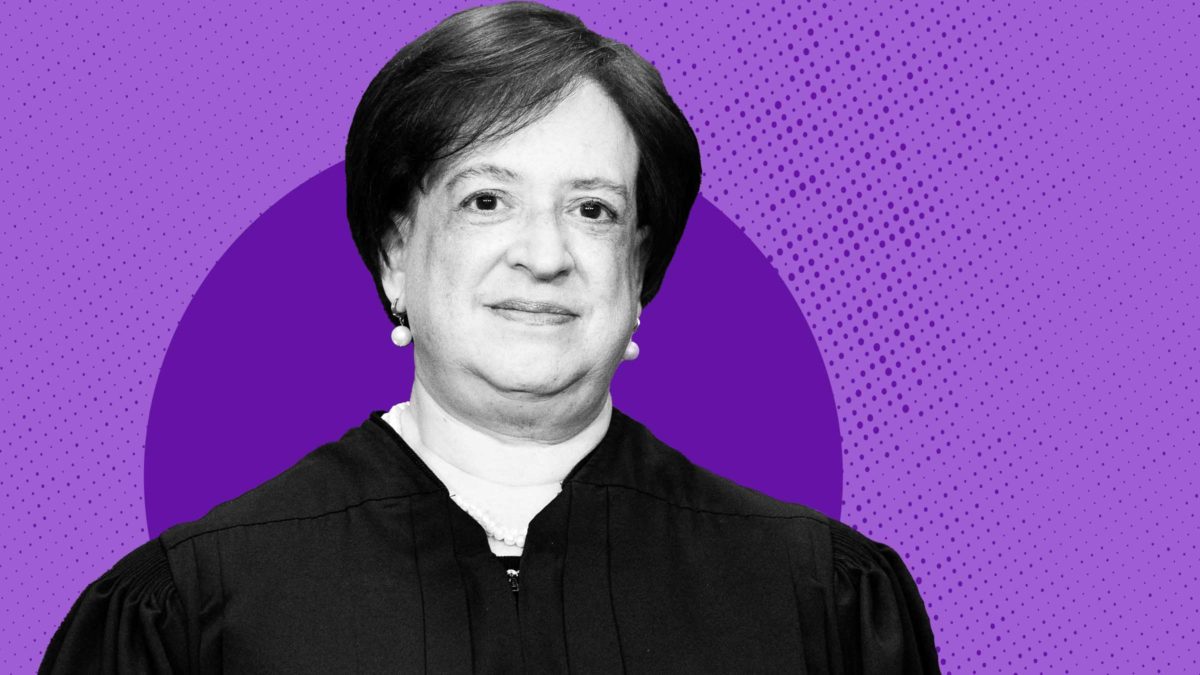

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the justices’ skepticism, Justice Elena Kagan’s majority opinion instructs lower courts to reconsider whether a facial challenge makes sense in these cases — effectively, whether NetChoice bit off more than it can chew in claiming that these laws are never constitutional. While this keeps the laws on ice and Internet law nerds like me happily employed for a few more years, it also punts a meaningful decision down the road—with a potential return trip to the Court that would force the justices to declare an ultimate winner in this specific culture war.

Though the lower courts will need to sort through the issues more finely, Kagan deftly does two things with the balance of her opinion: provide some semblance of a standard, and rebuke the Fifth Circuit for once again making an unprincipled hash of precedent in the pursuit of conservative politics. The main takeaway of the opinion, procedurally: “It is necessary to say more about how the First Amendment relates to the laws’ content-moderation provisions, to ensure that the facial analysis proceeds on the right path in the courts below.” Kagan then sets forth some guidelines on what editorial discretion covers, largely tracking the Eleventh Circuit’s analysis that ruled in favor of NetChoice.

The Fifth Circuit fares less well in Kagan’s view, who notes that the need for guidance “is especially stark” for that court. She repeatedly, though politely, criticizes the Fifth Circuit for its clear errors, as when it asserted that the Texas law didn’t affect speech or that Texas had a legitimate state interest in “improving” the marketplace of ideas. Those claims were obviously wrong to anyone who understands that the First Amendment doesn’t allow the government to recalibrate public discourse. Yet the ultraconservative Fifth Circuit—in its quest to validate Texas’s decision to throw red meat to right-wingers by slapping down allegedly left-leaning technology companies—bent over backwards to uphold the Texas law, since supporting conservative priorities trumps even the Constitution the ultra-right claims to hold so dear.

Reading a Fifth Circuit culture war opinion (Photo by ImageCatcher News Service/Corbis via Getty Images)

NetChoice marks the second time in less than a week that the Supreme Court has had to chastise the Fifth Circuit for grossly misunderstanding the First Amendment. Last week’s decision in Murthy v. Missouri, the jawboning case that the court dismissed on standing grounds, featured both subtle and direct critiques of the lower courts from Justice Amy Coney Barrett. The plaintiffs in Murthy—a mix of fringe commentators and red state attorneys general—claimed that the Biden administration’s communications with social media companies about COVID-19 misinformation constituted excessive governmental pressure in violation of the First Amendment. In Barrett’s words, the Fifth Circuit was “wrong” to grant an injunction barring federal government actors from speaking with tech platforms about misinformation; it approached the standing inquiry with a “high level of generality”; and it relied upon the District Court’s “clearly erroneous” findings. The disdain drips off the page, just as in NetChoice.

Our favorite flag enthusiast, however, wrote separately in NetChoice to underscore why the Fifth Circuit feels so emboldened to do whatever it wants when it comes to speech. In a concurring opinion in NetChoice, Justice Samuel Alito breathlessly opens by claiming that everything beyond the majority’s “narrow” holding regarding facial challenges is “nonbinding dicta” and goes on to refute much of Kagan’s guidance, characterizing it as “unnecessary and unjustified.” He provides his own view of why NetChoice can’t succeed on the merits because Texas and Florida are fully justified in regulating content moderation—a view that I expect the Fifth Circuit will warmly consider on remand.

As I’ve observed, one can’t be too cynical about the Fifth Circuit’s interest in ignoring First Amendment precedent (and any other precedent) when it wants to pursue its own political goals. It’s remarkable how explicitly the justices, from across the ideological spectrum, have spent the last week chastising the lower court for its brazen circumvention of law. But it’s depressing to recall how unlikely the Fifth Circuit is to change.