For the second February in a row, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in a pair of cases that could upend the Internet. Unlike last year, when they ultimately decided not to revisit the doctrine that protects social media companies from most lawsuits, this time, the justices probably won’t have the option to punt on a decision. If Gonzalez v. Google posed (and then ducked) the question “Should we, nine unelected justices with no legislative expertise, take on the responsibility of rewriting the federal law that facilitated the modern Internet?”, this year’s installment asks “Do we, a Court that has vastly expanded the scope of the First Amendment to support deregulatory corporate goals, think it’s constitutional for conservative states to tell social media companies they must host racist, conspiratorial, or explicit content?”

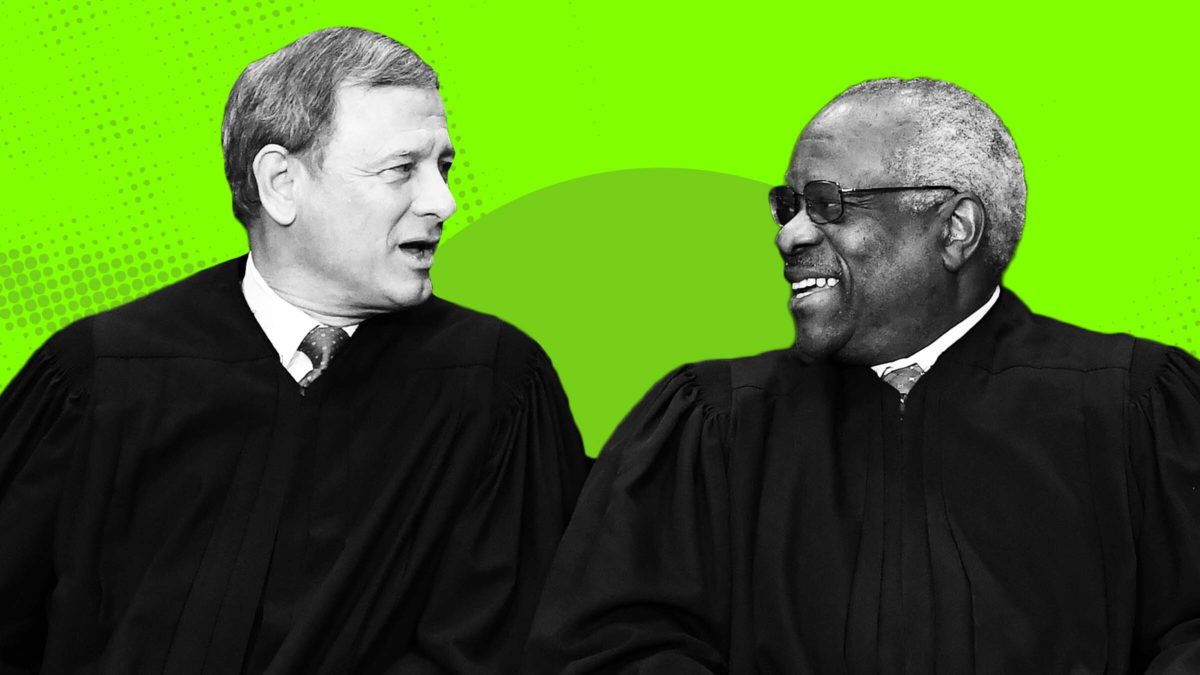

The current season of SCOTUS Goes Online consists of two cases arising out of Florida and Texas, Moody v. NetChoice and NetChoice v. Paxton. The NetChoice cases bring two favorite pastimes of conservative Supreme Court justices into conflict: weaponizing the First Amendment to deregulate something important (remember Citizens United?), and combating perceived “anti-conservative bias,” in this instance perpetuated by social media companies. Although the story of two decades of the Roberts Court is giving corporations what they want, multiple justices have repeatedly referenced their concerns for powerless conservatives, especially those who might be silenced by California tech companies. Justice Clarence Thomas has most explicitly signaled his interest in curtailing the power of social media platforms in opinions that nominally support denying certiorari, but also imply to careful readers exactly what types of cases might pique his interest in the future.

The Texas and Florida legislatures, both of which are controlled by Republicans, responded to these concerns. In 2021, both states enacted laws that severely restricted social media companies’ abilities to remove posts, ban accounts, and arrange content. Both laws also levied “transparency requirements” upon platforms, which would require them to explain why they remove certain content or accounts and publish their content moderation policies.

Lest one think the states acted with deliberation and nuance in addressing these intricate issues, Greg Abbott described Texas’s bill as intended to stop “a dangerous movement by social media companies to silence conservative viewpoints and ideas.” One of the Texas sponsors invoked “West Coast oligarchs” when he introduced the bill. Governor Ron DeSantis invoked James O’Keefe of Project Veritas as a victim of tech company bias when he signed Florida’s bill into law—with O’Keefe standing right behind him the entire time. Of course, the regulated entities realized the existential threat that these statues posed to their operations. NetChoice, a trade association that counts many social media companies among its members, filed suit in federal court in both states challenging the laws on First Amendment grounds.

(Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images)

There are no heroes in these cases. Social media companies have facilitated communication to a degree unimaginable even thirty years ago, connecting individuals and communities that have led to social progress in many ways. The companies have also fostered the proliferation of incredibly depressing and hateful content that has imperiled individuals and groups worldwide. They almost always dodge any real responsibility for their mistakes. On the other side of the disputes, Ron DeSantis and Greg Abbott have built their careers on fanning the flames of conservative grievances, from demonizing immigrants and refugees to supporting the banning of any books that even hint at the promise of a multiracial, pluralistic democracy. In the abstract, the prospect of greater control over how social media influences American and global society might have some intuitive appeal, but these bad faith laws hardly qualify as thoughtful regulatory intervention into a tricky economic, political, and social problem.

I’m thus sympathetic to NetChoice’s arguments; because of the poor drafting and sweeping effects of these laws, I filed an amicus supporting NetChoice’s 11th Circuit appeal in November 2021, and co-wrote another amicus supporting NetChoice in the Supreme Court cases in December 2023. But because social media companies play such a large role in influencing the social and political discourse domestically and internationally and have vast economic power, I worry that a broad Supreme Court ruling for NetChoice could effectively insulate social media from regulation, creating further problems for our fragile democracy. One can take issue with Florida and Texas’ laws while still realizing that some better-crafted regulatory efforts, particularly around transparency, could promote legitimate governmental needs.

(Photo by Paul Hennessy/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

My concerns about the repercussions of a win for NetChoice stems from my belief that it will probably prevail here. The prospect of state management of private parties’ speech raises many classic First Amendment problems. Over eighty years ago the Supreme Court ruled in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette that a state could not require students who were Jehovah’s Witnesses to salute the flag or say the Pledge of Allegiance. Since Barnette, private parties have found great success in invoking the specter of compelled speech when challenging some governmental mandates. Last term, in 303 Creative v. Elenis, a plaintiff opposed to same-sex marriage who planned to start a website design business raised the prospect of compelled speech. She claimed that because a gay couple might one day force her to design their website under Colorado’s anti-discrimination ordinance, her speech interests were implicated. Despite all the hypotheticals, the plaintiff’s compelled speech claim prevailed.

Even beyond Barnette, the social media companies have multiple cases on their side. In Miami Herald v. Tornillo, Florida’s mandate that newspapers give a “right of reply” to political candidates was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Pacific Gas & Electric Co. v. Public Utilities Commission held that California could not require a public utility to carry newsletters in its billing notices, even if the costs were minimal. In Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, the Supreme Court held that a Massachusetts anti-discrimination ordinance could not require parade organizers to host a group whose views they disagreed with.

These cases, which make up a loosely defined “editorial discretion” doctrine, generally protect the expression rights of private entities from governmental management or compulsion. In the NetChoice cases, the companies argue that they are like the newspaper in Tornillo or the parade organizers in Hurley and thus cannot be compelled by the state to carry content that they do not wish to carry. In its briefing, NetChoice argues “[a] website thus has just as much of a right as a newspaper, cable television provider, publishing house, bookstore, or movie theater to “exclude a message” it does not like.”

These views, I think, largely ignore the ways in which social media companies attempt to create (albeit imperfectly) a specific speech environment. Facebook and Instagram almost completely limit nudity. X has become much more hospitable to conservative speakers, like Parler and TruthSocial. TikTok doesn’t allow content about some political leaders. Though each platform might not perfectly and consistently create its own speech environment, newspapers don’t always hew to the party line on their editorial pages. Editorial discretion doesn’t require perfect adherence to the viewpoint that a private entity propounds; on social media, the messiness is part of the draw.

NetChoice doesn’t explicitly argue this point in its briefs, probably because most of its members want to preserve some semblance of openness to as wide an audience as possible. Part of the mess of content moderation stems from platforms that don’t want their customers to realize that the companies constantly stage-manage their user experience. Behind the screen so much content gets quickly removed for violating policies, and calibrating that reputation for openness while making tough decisions on what breaks the rules requires massive investment and human decision making. Introducing a level of state management into private entities’ content moderation would make the platforms a completely different space at best and facilitate the suppression of unpopular views at worst.

(Photo by Michael Gonzalez/Getty Images)

Because the public now relies upon corporations to disseminate much of our individual speech, the justices probably realize they need to give social media companies significant freedom from state intervention. Indeed, one can read the Court’s decision in Gonzalez v. Google, which declined to change the Section 230 status quo that the conservatives so dislike, as a determination that protecting private corporations matters more than validating right-wing grievances. But the court could easily compound the very real issues with social media and technology—such as the spread of disinformation, the possibilities of election interference, and the lack of visibility into how and why platforms make content moderation decisions—by ruling that states and the federal government can never enact social media regulations.

I’m not terribly worried that the Court will validate the states’ misguided laws—I hope they overturn them. But closing all paths to social media regulation would create a nearly unprecedented situation in which an economically and socially influential industry remains immune from any kind of regulatory intervention. Such a blithe, hasty ruling would hardly be worth celebrating. •