The Supreme Court heard oral argument in Moore v. Harper on Wednesday, a case about the congressional redistricting process in North Carolina and who has control over it. But the eventual ruling in Moore could also grant state legislatures near-total power over federal elections—at this particularly fragile juncture in U.S. history, an outcome with perhaps-fatal consequences for representative democracy.

Moore is about the “independent state legislature” theory (ISLT), an idea increasingly popular on the legal right, which posits that state lawmakers have sweeping power over federal elections based on the Constitution’s grant of power to the “Legislature” to set the “time, place, and manner” of elections. Proponents have different views of how much of this authority belongs exclusively to state lawmakers, though. Some say it is constrained by all the usual constraints of divided government: governors, state courts, and state law. Others say that under the text of the Constitution, lawmakers have the power to do, more or less, whatever they want.

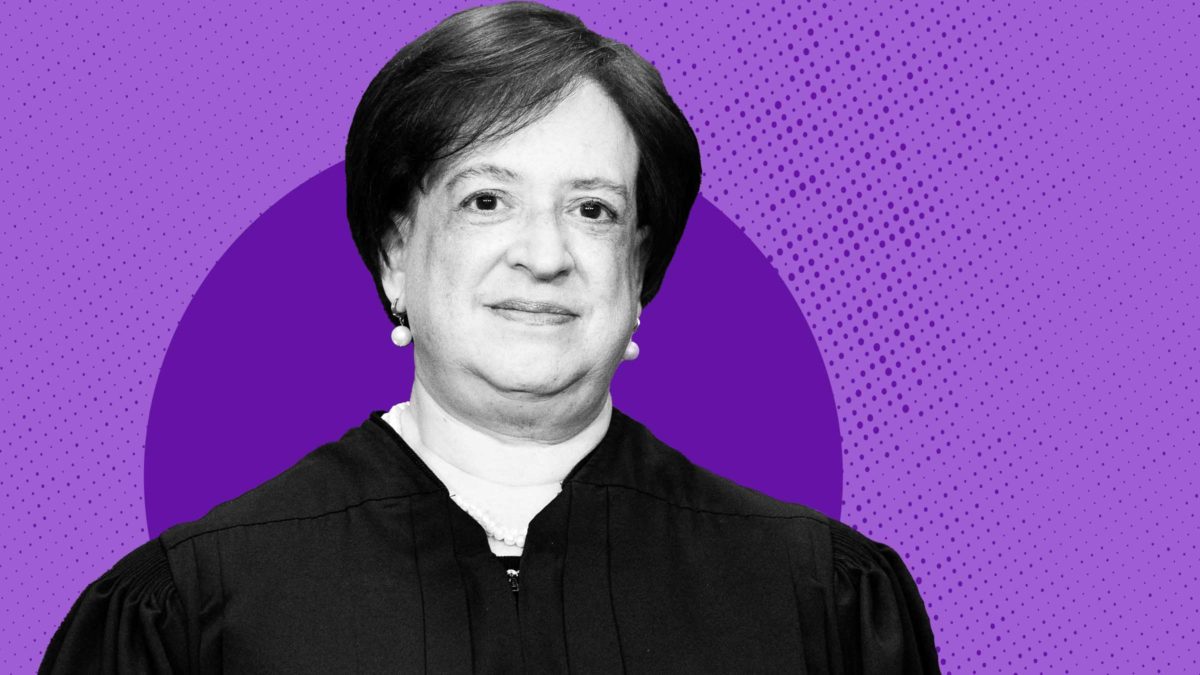

The Court’s three liberals—Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson—made clear their unwillingness to adopt any version of the ISLT. (At various points, Sotomayor said that the arguments from the lawyer for North Carolina Republican lawmakers made “little sense” and “no sense” to her.) But in the aftermath of an election that a defeated Republican presidential candidate very much tried to steal with the help of his colleagues on Capitol Hill, it was Kagan who stepped outside the legal minutiae of the case to discuss the “big consequences” of the ISLT’s potential adoption.

“If a legislature engages in the most extreme form of gerrymandering, there is no state constitutional remedy for that,” Kagan said. “It would say that legislatures could…get rid of all kinds of voter protections,” and allow lawmakers to “insert themselves in the certification of elections and the way election results are calculated.”

Kagan: “This is a theory with big consequences. … It gets ride of the normal checks and balances on the way big governmental decisions are made in this country. You might think it gets rid of all those checks and balances at exactly the time that they are needed most.” pic.twitter.com/31oyODrPXd

— Mark Joseph Stern (@mjs_DC) December 7, 2022

“This is a proposal that gets rid of the normal checks and balances on the way big governmental decisions are made in this country,” Kagan concluded. “And it gets rid of all those checks and balances at exactly the time when they are needed most.”

Kagan’s soliloquy centered the practical implications of the ISLT’s abstractions: If the Court were to declare that state lawmakers have unchecked power over every aspect of federal elections, incumbents will have powerful incentives to abuse it. In 2020, allies of President Donald Trump leaned heavily on the ISLT in their doomed attempts to secure state-level recounts. If a future Republican presidential candidate—perhaps Trump again—were to seek to undermine the integrity of a future election, a robust ISLT would make their path a whole lot easier.

Most of the conservative justices seemed skeptical of the strongest version of the ISLT on Wednesday. Many of their questions assumed the existence of at least some level of state court power, and focused instead on nailing down a standard for when federal courts can overrule state court rulings on questions of state election law in the future. (Among the standards discussed were described as “incredibly high,” “sky-high,” and “stratospheric,” none of which would be good for ISLT enthusiasts.) Only Justice Neil Gorsuch, who spent an uncomfortable amount of time asking questions attempting to link opposition to the ISLT to the Three-Fifth Clause, sounded willing to embrace the theory wholeheartedly.

Much of Supreme Court oral argument is about reimagining high-stakes policy decisions as complex, technical legal questions. It is for this reason that the conservative legal movement focused so heavily on control of the federal courts in the first place: appellate procedure has a funny way of disguising unpopular policy positions in inscrutable jargon. Kagan’s focus on the real-world consequences refocused the Court, if only for a moment, on the political context in which it will decide Moore. The legal system does so much harm in the dark; Kagan did her best to push it into the sunlight.