In a two-sentence order issued on Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court greenlit Texas’s efforts to execute Jedidiah Murphy, over the objections of Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson. Several hours later, as the annual observance of World Day Against the Death Penalty came to a close, officials at the state penitentiary in Huntsville killed Murphy by lethal injection.

If a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit had had his way, the Supreme Court wouldn’t even have needed to act. In a 2-1 decision on Monday, a three-judge Fifth Circuit panel upheld a lower court’s stay of Murphy’s execution while his lawyers challenged evidence used to sentence him to death. The lone dissenter was Jerry Smith, whom President Ronald Reagan elevated to the country’s most conservative federal appeals court in 1987. “The majority opinion is grave error,” Smith wrote, excoriating his colleagues for buying “a vapid last-minute attempt to stay an execution that should have occurred decades ago.”

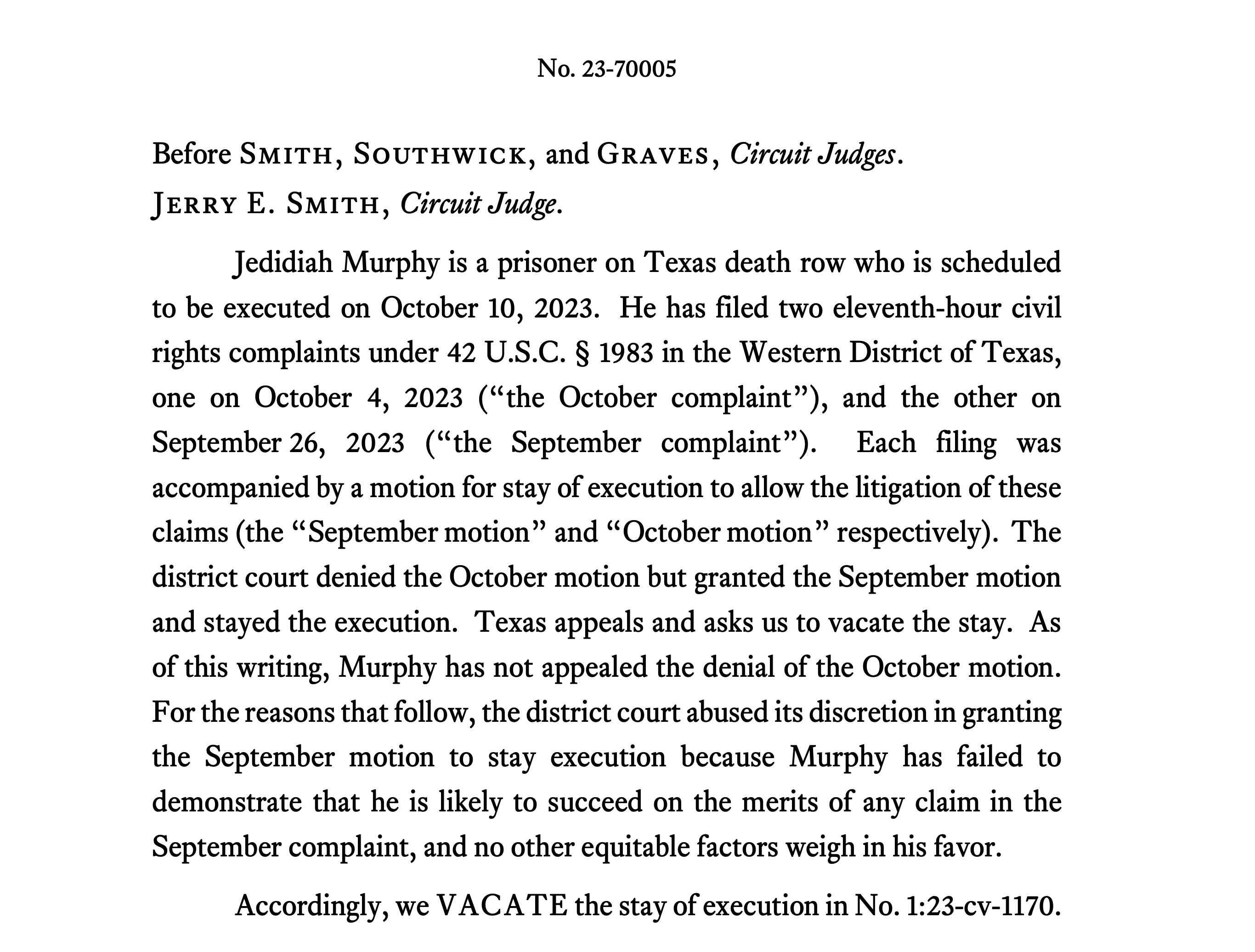

All of this sounded like standard-issue Reagan appointee bloodlust, but what followed was not. “In the interest of time, instead of penning a long dissent pointing to the panel majority and district court’s myriad mistakes, I attach the Fifth Circuit panel opinion that should have been issued,” Smith wrote. Sure enough, he then included what looks like a real majority opinion that purports to vacate the stay and allow Texas to move ahead with Murphy’s execution. At 18 pages, Smith’s fake majority opinion is more than three times longer than the actual majority opinion, and explains in painstaking detail on behalf of a nonexistent unanimous panel why Jedidiah Murphy should have been dead already.

I cannot stress enough how deranged this is: a life-tenured federal judge so incensed about what amounted to a 24-hour stay of execution that he decided to uncork a fake majority opinion to complain about it. As Chris Geidner points out at Law Dork, there is nothing about Smith’s exercise in barbaric fanfiction that makes clear that it is, in fact, barbaric fanfiction. A casual reader would have no reason to treat the document as anything other than legitimate, and it feels like only a matter of time before some poor bastard working too late at night on a death penalty appeal accidentally cites it as such.

The majority opinion—the actual one—was written by George W. Bush appointee Leslie Southwick and Barack Obama appointee James Graves. In it, they explain that they were merely waiting to rule on the stay of execution pending the results of a related Fifth Circuit case. Although they at one point refer to Smith’s “alternative opinion,” the majority otherwise engages with Smith’s arguments as if he’d included them in a normal dissent. In other words, if Southwick and Graves feel anything in particular about a disgruntled colleague’s decision to publicly air them out with a whole-ass fake majority opinion that more or less calls them embarrassing morons, neither of them felt compelled to mention it.

This silence, from the Fifth Circuit and elsewhere in the federal judiciary, does not really surprise me. Few constituencies in this country are as obsessed with collegiality and decorum as members of the legal profession, who dutifully refer to their courtroom opponents as “my friend” no matter how obviously they hate each other’s guts. Judges, whose idea of fighting words is the purposeful omission of the word “respectfully” from a dissenting opinion, are even more egregious sticklers for performative civility.

Stories like this one, however, illustrate how the profession’s rigid adherence to such norms can do the public a real disservice. Putting your colleagues’ names on a losing argument that you insist they would have joined if they weren’t such rubes is (sorry for the legal jargon here) a real dick move, especially given the seriousness of the subject matter. There should be consequences for pulling stuff like this, even if those consequences are limited to social opprobrium; in just about any other setting, at least a few of Smith’s hundreds of colleagues would correctly call this out as an offensive stunt by an unserious crank desperate for attention. Instead, Texas got its wish, Jedidiah Murphy is dead, and Jerry Smith’s chambers are about to be inundated with fawning cover letters and mediocre writing samples from edgelord law students vying for an Alito clerkship.

Many pundits and academics on the right maintain that some daylight exists between the conservative legal movement and the Republican Party’s full-on embrace of Donald Trump: Politicians may say and do boorish, uncouth things, sure, but judges—respectable people who do law, not politics—would never stoop to such unseemly depths. As Smith demonstrates, this is naive wishcasting at best. Republican judges understand that right now, the surest path to praise, prominence, and promotion within the conservative legal movement is to find creative new ways to own the libs. When a game doesn’t have real rules, the players who are most willing to ignore them are generally going to come out on top.