In 2018, the Tennessee Department of Corrections brought Harold Wayne Nichols from death row to the Hamilton County Courthouse. He didn’t think he’d be going back to death row afterwards; his attorneys were meeting him at the courthouse, along with Hamilton County District Attorney Neal Pinkston, who had agreed with Nichols’s attorneys to resentence him to life in prison. This hearing, before Senior Judge Don Ash, was supposed to be a formality to finalize what the attorneys had already worked out.

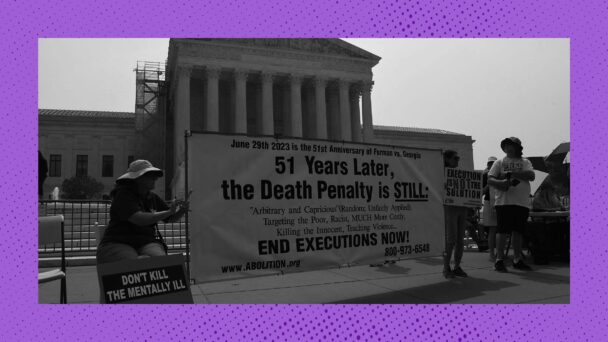

Resentencing is not uncommon for death penalty cases in the United States, where the most likely outcome for a death sentence is that it is eventually overturned. Issues like ineffective assistance of counsel and prosecutorial misconduct are rife in capital cases, and sometimes, during the appeals process, prosecutors see where the system has failed and agree to impose a lesser sentence.

In the courtroom, though, Ash shocked everyone when he rejected the agreement and sent Nichols back to death row, where he’s remained ever since. Unless Tennessee’s governor, Republican Bill Lee, agrees to commute his sentence to life without parole, barring a last-minute court intervention, Nichols will be executed on December 11.

Lee is in a strange position as he considers Nichols’s clemency request. The elected district attorney, who pushed for a life sentence during Nichols’s appeals process, does not want Nichols executed. The jury doesn’t want Nichols executed, either: When interviewed after his trial, half the jurors expressed that they intended their death sentence to be a de facto term of life, after being misled by a prosecutor’s improper remarks. But over and over, the legal system has turned Nichols away. As a result, even though multiple district attorneys who prosecuted him and the jury who sentenced him do not want Nichols executed, he is scheduled to die next week.

Nichols at his sentencing (screencap via YouTube)

In 1990, Nichols pleaded guilty to raping and murdering Karen Pulley two years prior. But he still went before a jury, because after the Supreme Court’s 1976 decision in Gregg v. Georgia, death penalty cases are split into two trials—one to determine a defendant’s guilt, and one to determine a sentence. During his sentencing, Nichols expressed remorse for his actions, stating, “If I could change places with Karen, I would.” But the jury also had to decide whether the aggravating factors presented by the state, which included Nichols’s previous rape convictions, outweighed Nichols’s willingness to take responsibility for his crimes, as well as what the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals described as Nichols’s “oppressive and forlorn childhood” riddled with physical and sexual abuse.

In its closing arguments, the prosecution argued that the jury must sentence Nichols to death, or else he would be released and commit more horrific crimes. Jurors ultimately decided to impose a death sentence, but not without hesitation, because at the time, Tennessee had only two sentencing options for capital crimes: death, or life with the possibility of parole. The state also had not carried out an execution in thirty years. In the years since Tennessee resumed conducting executions in 2000, six of the jurors in Nichols’s case have reiterated that they never thought or wanted his case to come to this: One said that it was never their “intent that the Petitioner be put to death,” and that the jurors “believed if we sentenced [Nichols] to death he would never be executed because [Tennessee] never executes people.”

On appeal in 1994, Nichols argued that the prosecutor’s statements about Nichols’s future dangerousness violated his constitutional rights. Supreme Court precedent and Tennessee juror instructions bar jurors from imposing a death sentence based on such speculative, generalized fears; instead, jurors must weigh specific aggravating and mitigating factors laid out by statute. Nichols’s lawyers contended that the prosecutor’s remarks were inflammatory and unfair, in that they essentially scared the jury into voting for death.

Tennessee’s chief justice at the time, Lyle Reid, found this argument persuasive, calling the prosecutor’s language a “dramatically clear” warning that “unless the defendant is sentenced to death he will be released from prison and rape again.” But Reid’s colleagues on the Tennessee Supreme Court disagreed and affirmed Nichols’s sentence. “After carefully considering the entire record, and the factors discussed above, we have determined, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the sentence would have been the same had the jury given no weight to the invalid felony-murder aggravating circumstance,” they wrote.

In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Johnson v. United States gave Nichols another chance at avoiding execution. In that case, the Court invalidated a federal sentencing law that included unconstitutionally vague language about the relevance of defendants’ prior violent convictions. Because of Johnson, Judge Ash allowed Nichols to reopen his post-conviction proceedings, and District Attorney Neal Pinkston identified not one but two constitutional issues with Nichols’s sentence: first, that the trial prosecutor’s warnings were unconstitutional under Johnson, and second, that the Tennessee Supreme Court’s reweighing of Nichols’s aggravating and mitigating factors put the judiciary in the role of the jury, in violation of the holding of another 2015 Supreme Court decision, Hurst v. Florida.

With both recent Supreme Court caselaw and the sitting prosecutor on his side, Nichols had reason to feel optimistic when he went before Judge Ash in 2018. But instead, Ash found that neither Johnson nor Hurst were retroactive or applicable to Nichols’s case, and therefore there was no valid reason for Ash to accept the proposed resentencing settlement. The prosecutor who’d negotiated the deal, Assistant Hamilton County District Attorney Crystle Carrion, called Ash’s decision an “injustice to Mr. Nichols,” and said she’d never “experienced or heard of another case in which a court wholesale rejected an agreed upon case disposition.”

Nichols fared no better at the U.S. Supreme Court. When he sought the justices’ intervention in 2020, the Court declined his petition for a writ of certiorari without comment. Nichols’s lawyers will likely file for an emergency stay of his execution, but the justices typically wash their hands of constitutional issues in capital cases: To date, states have executed 44 people in 2025, the most in any single year in more than a decade. The Court has refused to take up a single one of these cases.

Nichols’s case embodies so many of the problems with the criminal legal system’s inconsistencies in who is executed, and who isn’t: arbitrary decisions, pressure on juries to impose a death sentence on someone they do not want to see die, and procedural rules that supersede common sense. Lee’s singular ability to grant Nichols clemency is a necessary power to address these limitations of the courts. It is an avenue for mercy and humanity in a system that often denies both. And it is an increasingly essential check against too-powerful judiciaries that turn a blind eye to both basic human decency and to the constitutional protections they have the responsibility to uphold.