The dog days of summer are upon us, which means it is time for plugged-in Supreme Court reporters to empty their notebooks and publish juicy anecdotes from the most recent term, which will one day form the backbone of a tell-all book that collects dust on my shelf.

CNN’s Joan Biskupic published two such stories earlier this week, pulling back the curtain on a pair of the Court’s highest-profile recent cases: one about Idaho’s near-total abortion ban, and the other about presidential immunity from criminal prosecution. In the first case, Moyle v. United States, the justices considered whether Idaho could enforce its ban even when patients are in serious medical danger. The Court punted, preventing the ban from taking effect as litigation continues, but reserving their right to revisit the matter in the future (perhaps when the 2024 election is safely over). The Court was not nearly as shy in the second case, Trump v. United States, issuing a sweeping ruling that all but guarantees that Trump won’t face liability for his myriad crimes, January 6-related and otherwise, before voters go to the polls this fall.

According to Biskupic, when Moyle first came before the justices in January, the split was 6-3 along the usual lines: All the conservatives wanted to let Idaho enforce its ban, and all the liberals wanted to block it. But at oral argument, Justice Amy Coney Barrett became alarmed by Idaho’s lawyer’s suggestion that the ban would prohibit doctors from providing abortion care to patients who would have to have a hysterectomy, thereby preventing them from having children ever again. When the justices re-voted, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, too, were having second thoughts, and without a “clear majority for any resolution,” Roberts took the unusual step of not assigning the majority opinion to anyone. Instead, the three of them began working on an opinion that would dismiss the case as improvidently granted, which would return it to the courts below for further proceedings.

The challenge for Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, of course, was that Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch did not find this result remotely troubling, and were ready to let the ban take effect. They thus initiated a “series of negotiations” with the liberal justices, and eventually got Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan to sign on to an awkward compromise: The two liberals would vote to dismiss the case for now, if the three conservatives would agree to block the ban from taking effect in the meantime. (Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote separately, dissenting from the Court’s decision to dismiss the case.) For once, Biskupic says, the liberals had some real “bargaining power,” and used it to prevent Idaho from forcing women to get airlifted to other states to avoid bleeding to death.

To the extent that Supreme Court justices, as the internet’s most pedantic law professors often suggest, endeavor to “do law, not policy,” it is striking how little “law” features in Biskupic’s narrative. The story of the case is not, for example, a thoughtful difference of opinion about the outer limits of federal preemption doctrine; it is, instead, a practical bargain between three anti-choice justices reluctant to make waves during an election year, and two pro-choice justices willing to bargain in the interest of holding off a different coalition of anti-choice justices who had fewer reservations about plowing ahead. There isn’t a pertinent difference between this and grimy congressional horse-trading on legislation, other than the fact that this set of nine policymakers publicly swears they would never do anything of the sort.

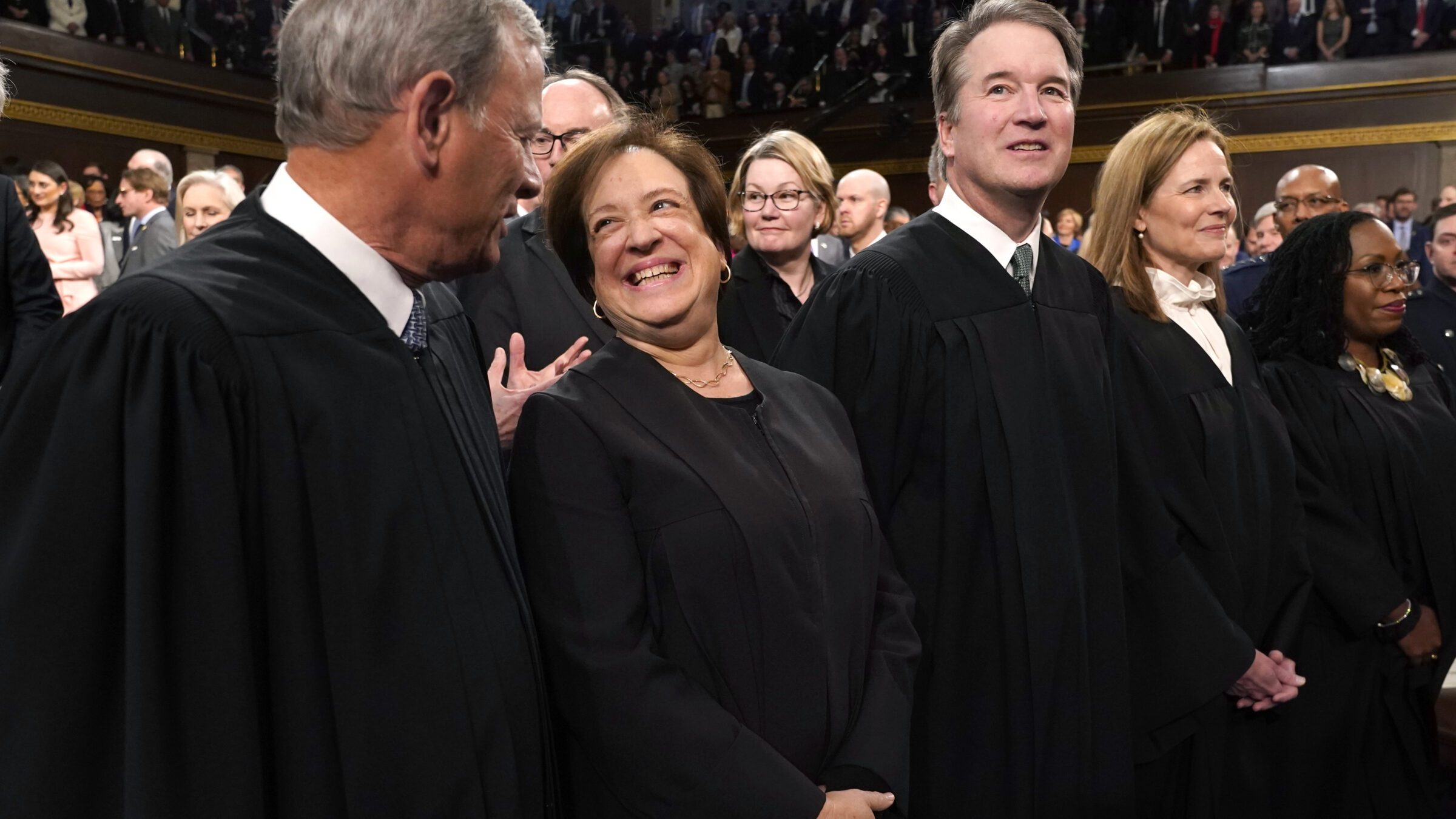

Entering the deal zone (Photo by Jacquelyn Martin-Pool/Getty Images)

Biskupic’s account of the immunity decision is very different. This time, she says, there was an “immediate and clear 6-3 split,” and that Roberts, who authored the majority opinion, was “ready to write with bold strokes” and made “no serious effort” to draft something that might persuade the liberals to join him. The three furthest-right justices, Biskupic adds, were “heartened” by his aggressiveness. For a long time, Roberts was the Republican justice who cared most about preserving the illusion of the Court’s impartiality; this term, it seems, he stopped giving a shit.

Together, Biskupic’s two scoops are a grim reminder of just how stacked the odds are at the Supreme Court against anyone to the left of, say, Mitt Romney. Like many pundits, she frames the Idaho case as a “rare win” for the liberals, who could use their “leverage” to get what they wanted. But as usual, “what they wanted” in this context isn’t anything new. The result doesn’t strengthen individual rights, or protect marginalized people from abuses of power, or otherwise move the law to the left. All the liberals got in Moyle was a temporary, fragile preservation of the status quo, with a very real chance that when the ban inevitably returns to the Court, the six conservatives will find a reason to stick together to uphold it.

For Kagan and Sotomayor, this was a “win” in the sense that me not getting struck by lightning yesterday was a “win”: Sure, I’d be in worse shape today if that had happened to me, but the fact that it didn’t doesn’t mean I’m doing “better” in any meaningful sense.

Conservative victories, meanwhile, are far more impactful: Together, the six Republican justices invented a doctrine of sweeping criminal immunity for a former president (and current presidential nominee) whose last official act was attempting to overthrow the government he ostensibly led. Cases like Trump v. United States extend the protections of constitutional law to the policy goals of the Republican Party, and move this country even further from functioning as the representative democracy it aspires to be. Most importantly, they vest even more political power in unelected, life-tenured justices, who remain blissfully free to change their minds if future applications of their made-up rules lead to real-world outcomes they don’t like.

Biskupic’s “inside” stories of these cases is the story of basically every case that comes before this Supreme Court: When the stakes are highest, the conservatives always win the game. The only question is how close the liberals managed to make it look.