In 2005, 19-year-old Kevin Johnson shot and killed William McEntee, a police officer in Kirkwood, Missouri, whom Johnson blamed for the death of his 12-year-old brother just hours earlier. When Johnson turned himself in, he asked police to let him see his young daughter, Khorry Ramey, one more time. They refused. Johnson was tried, convicted, and sentenced to die by lethal injection.

Earlier this month, Ramey, who is now also 19, had a request of her own: Although state law prohibits anyone under 21 years of age from viewing executions, she wants to be allowed to be present at her father’s death. “My dad is the most important person in my life,” Ramey said. “He has been there for me my whole life, even though he’s been incarcerated.” Johnson, too, wants his daughter there; in October, he met his grandson, Ramey’s child, and was even allowed to take a picture with the two of them.

Last week, however, a federal district court judge denied Ramey’s petition, finding that the state has a legitimate interest in, among other things, “preventing teenagers from witnessing death” and “preserving the solemnity of the execution.” After his other legal appeals were exhausted, Johnson’s execution, scheduled for 6 P.M. local time on Tuesday, went ahead as scheduled. He was pronounced dead at 7:40 P.M.

Kevin Johnson has no final statement and he declined his last meal. pic.twitter.com/wPf3XSb0Kc

— Alexis Zotos (@alexiszotos) November 30, 2022

In his order rejecting Ramey’s request, Judge Brian Wimes of the Western District of Missouri deferred to the state’s contention that teenagers might “exhibit impulsive and unpredictable behavior that could cause a security threat,” and might not be “old enough to comprehend the events of the execution and be able to give an accounting of the process.” (Apparently, a 19-year-old woman who has spent her entire life visiting her father in prison poses too grave a threat to a room full of armed guards to even allow her to set foot inside it.)

Johnson, whose case has been covered extensively by Liliana Segura and Jordan Smith at The Intercept, has a history of serious mental illness: He attempted suicide at 14, and has been held in a psychiatric hospital multiple times, according to his lawyers. He killed McEntee after Johnson’s brother, Joseph Long, died after suffering a seizure while police were at the family home to arrest Johnson for a parole violation. Johnson believed that the responding officers, including McEntee, were too preoccupied with arresting him to help his dying brother.

Last month, Johnson’s lawyers argued to the U.S. Supreme Court that youth offenders like Johnson shouldn’t face the death penalty, given the scientific consensus that the parts of the brain that govern impulse control do not mature until well after age 21. But Johnson’s age at the time of the murder is not the only troubling aspect of his conviction and sentence. In October, a Missouri state court judge appointed a special prosecutor to investigate claims of racial bias that tainted Johnson’s trial, based on a 2021 Missouri state law that allows prosecutors to revisit wrongful convictions.

That special prosecutor concluded that race played a “decisive factor” in Johnson’s case, and recommended that the court vacate his death sentence. (The prosecutor who obtained Johnson’s conviction tried five cases involving the deaths of police officers; he sought the death penalty for all four Black defendants, but not for the lone white defendant.) After a state court judge refused to do so, Johnson’s lawyers appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court.

None of his appeals proved successful. On the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, the U.S. Supreme Court turned away Johnson’s appeal with no noted dissents. Then, on Monday, the Missouri Supreme Court voted to deny his request for a stay of execution. Judges Patricia Breckenridge and George Draper dissented, arguing that granting a stay would be the “only way” to not “infringe on the protections against wrongful convictions” that Missouri law provides.“The threat of irreparable harm absent a stay is obvious,” Breckenridge wrote. The U.S. Supreme Court denied Johnson’s appeal in this matter, too; only Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson noted their dissents.

Statement from Kevin Johnson’s lawyers: “Missouri capitally prosecuted, sentenced to death, and killed Kevin because he is Black.” pic.twitter.com/JHm4b4qYrP

— Chris “Subscribe to Law Dork!” Geidner (@chrisgeidner) November 30, 2022

Of the grounds on which Wimes denied Ramey’s request, the state’s purported interest in shielding young people from the specter of death is perhaps the cruelest. If 19-year-olds like Ramey are too young and impressionable to be allowed to witness a state-sanctioned execution, it stands to reason that 19-year-olds like Johnson are too young and impressionable to be put to death for crimes they committed at that age. And if executions—supposedly part of a fair, civilized justice system—are too horrific to allow adults to be in the room during their parent’s final moments, it raises the obvious question of how the state justifies carrying out these executions in the first place.

Update: On Wednesday, a day after Johnson’s death, the Court released a dissenting opinion from Jackson, joined by Sotomayor. “Johnson’s execution irrevocably mooted our consideration of his due process claim,” wrote Jackson. “Missouri would have suffered no discernible harm had a stay been issued.”

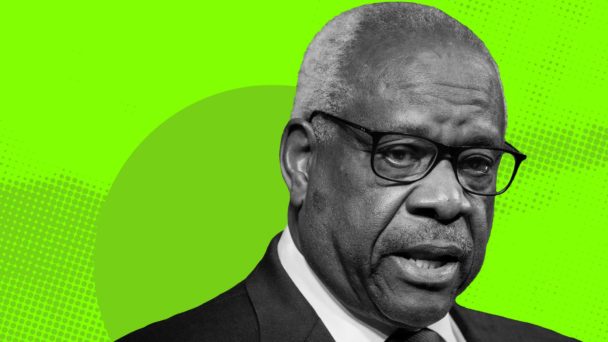

Header photo courtesy of the ACLU.