In 1977, after two decades on the U.S. Supreme Court, Justice William Brennan wrote a law review article summarizing three of the Court’s major achievements under Chief Justice Earl Warren. First, he highlighted the Warren Court’s groundbreaking equal protection decisions, headlined by Brown v Board of Education, which forbade racial segregation in schools, and Baker v. Carr, which imposed a “one person, one vote” standard in state legislative apportionment. Second, its due process jurisprudence, exemplified by Goldberg v. Kelly, which required state public assistance programs to provide recipients the opportunity for a hearing before termination of benefits. Lastly, Brennan lauded decisions related to the “administration of the justice system,” such as Mapp v. Ohio, which required state courts to exclude illegally seized evidence from criminal trials.

Brennan wrapped by reiterating the importance of the legal system’s role in protecting Americans from “arbitrary action” by the government. “Only if the amendments are construed to preserve their fundamental policies will they ensure the maintenance of our constitutional structure of government for a free society,” he wrote. “For the genius of our Constitution resides not in any static meaning that it had in a world that is dead and gone, but in the adaptability of its great principles to cope with the problems of a developing America.”

Yet Brennan also anticipated the reactionary movement ahead in which the Court would render “door-closing decisions” that limit the federal judiciary’s “protective role.” His prediction anticipated the court’s 2022 opinion in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization overruling Roe v. Wade, a precedent of five decades.

Brennan, once a New Jersey Supreme Court justice, had a proposed fix for this problem: He urged advocates to litigate in state courts, which, he said, “no less than federal are and ought to be the guardians of our liberties.”

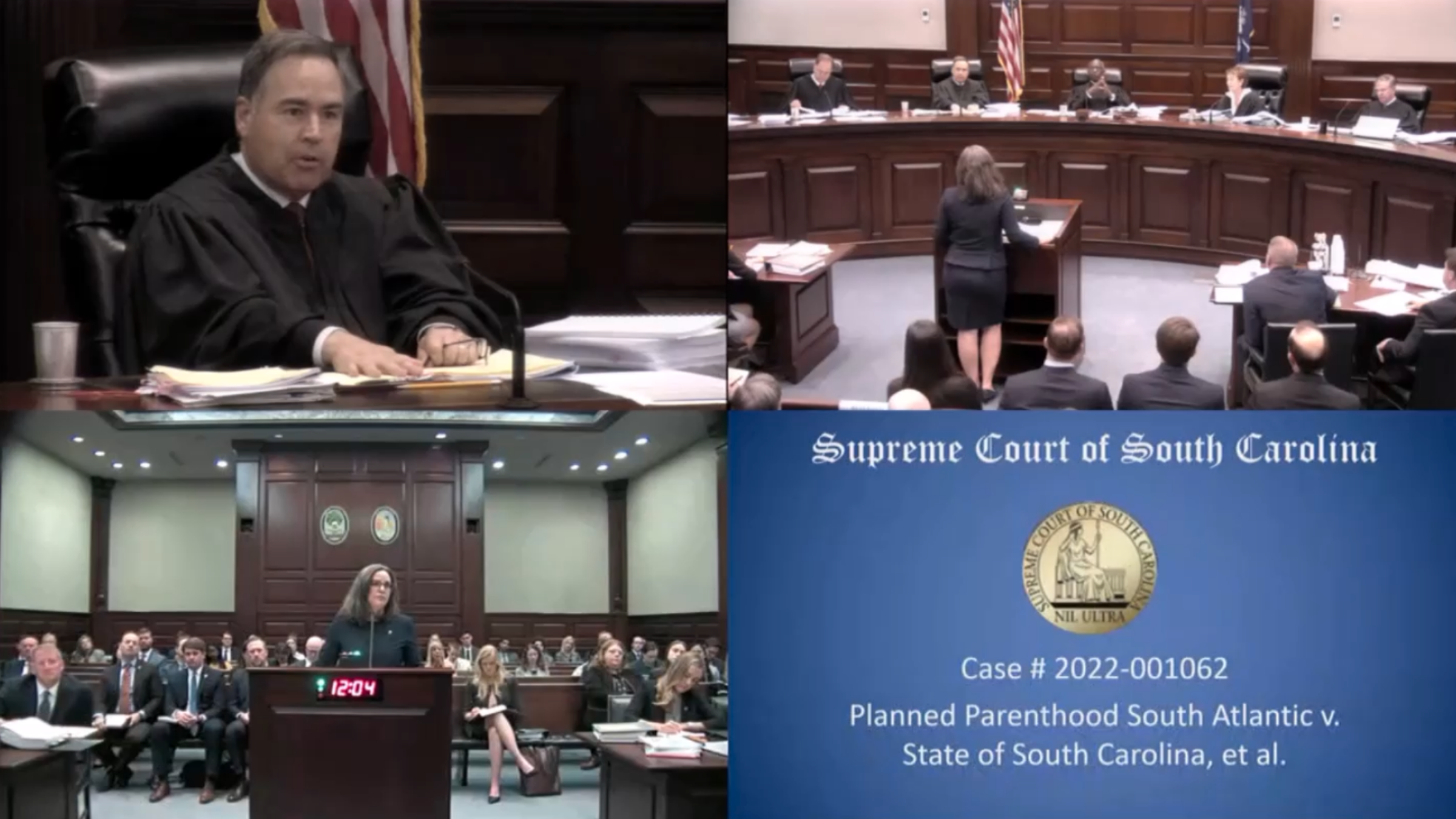

The South Carolina Supreme Court hears oral argument in Planned Parenthood v. State, October 19, 2022 (screencap via sccourts.org)

In the aftermath of Dobbs, some advocates are paying attention to this advice. On January 5, in Planned Parenthood South Atlantic v. State, the South Carolina Supreme Court held that the state constitution’s prohibitions against “unreasonable searches and seizures” and “unreasonable invasions of privacy” protected “a woman’s decision to terminate a pregnancy,” invalidating a state law prohibiting abortion after six weeks of gestation. Earlier this month, the North Dakota Supreme Court put the state’s abortion ban on hold, finding that the state constitution protects the “fundamental right to receive an abortion to preserve the life or health” of the pregnant person. And just last week, the Oklahoma Supreme Court carved out a broader exception to the state’s near-total abortion ban than the state’s Republican lawmakers hoped for.

Obviously, not every bid to protect fundamental rights at the state level will succeed. On the same day, a divided Idaho Supreme Court in Planned Parenthood Great Northwest v. State upheld sweeping restrictions on abortion, ruling that the state constitution’s “inalienable rights clause” did not “protect abortion as a fundamental right.” But together, the two cases show that even in a deep-red states, state courts have the power to issuing groundbreaking pro-civil rights decisions, even when the federal judiciary is hostile to them.

History shows how landmark expansions of individual rights can begin in state courts. In 1999, some 15 years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, the Vermont Supreme Court held that the state constitution’s declaration that government exists for the “common benefit, protection, and security of the people” required that the government extend “the common benefits and protections that flow from marriage” to same-sex domestic partners.

Four years later, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court recognized a right to same-sex marriage under the state constitution, reasoning that “the genius” of federalism is that each state constitution “has vitality specific to its own traditions.” Subject to the Fourteenth Amendment, the court continued, states could “address difficult issues of individual liberty” as their own constitutions might require, and protect “matters of personal liberty against government incursion as zealously” as the U.S. Constitution—if not even more so.

Then, in 2009, the Iowa Supreme Court, too, recognized a right to same-sex marriage, relying on language in the state constitution that prohibits granting “to any citizen, or class of citizens, privileges or immunities, which, upon the same terms shall not equally belong to all citizens.” Varnum summarized a string of Iowa cases that fulfill the “our constitution’s ideals” and affirm “absolute equality for all”: one in 1839 invalidating a contract for slavery 18 years before Dred Scott v. Sandford, and another in 1873 that struck “blows to the concept of segregation” decades before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board. Against this historical backdrop, denying legal protections to same-sex couples, the Varnum Court wrote, would be “an abdication of our constitutional duty.”

This is hardly the only instance of state supreme court rulings foretelling significant legal reforms. The California Supreme Court’s 1948 ruling in Perez v. Sharp declared marriage a “fundamental right,” nullifying the state’s anti-miscegenation statute almost two decades before the U.S. Supreme Court did so in 1967 in Loving v. Virginia. The Indiana Supreme Court’s 1854 decision in Webb v. Baird presaged by a century the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1963 decision in Gideon v. Wainwright, which requires states to appoint lawyers for indigent criminal defendants facing felony charges. The Wisconsin Supreme Court’s 1961 decision in Pines v. Perssion established implied warranties of habitability—critical for impoverished renters—well before federal courts did.

Sometimes, state courts have even extended rights under state constitutions beyond what federal courts have allowed. In State v. Marsala, for example, the Connecticut Supreme Court rejected a federal “good faith” doctrine that allows admission of illegally seized evidence, calling the exception to the exclusionary rule “incompatible with the constitution of Connecticut.”

Denny Schrock (L) and his partner Patrick Phillips celebrate after receiving their marriage license at the Polk County Administration Building, April 27, 2009 in Des Moines, Iowa (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Taking the fight to state courts is not without risks. Unlike Brennan, whose job was guaranteed for life under Article III of the federal Constitution, state court judges face elections, recalls, and uncertain retention or reappointment. In the election after Varnum, for example, Iowa voters ousted three members of the Court that decided the case. State courts can also face legislative attempts to expand or contract their memberships in response to controversial rulings. The same factors that can make state courts promising laboratories of litigation can also make sweeping decisions risky bets for the judges who write them.

Still, litigants and their advocates must recognize that Brennan correctly emphasized the potential of state courts to accomplish what reactionary federal courts cannot. In his law review article, Brennan offered a hardheaded, lawyerly reason for choosing to litigate in state courts: opinions resting “wholly or even partly on state law need not apply federal principles of standing and justiciability that deny litigants access to the courts,” he wrote. And such decisions “not only cannot be overturned by, they indeed are not even reviewable by, the Supreme Court of the United States.” He concluded frankly: “We are utterly without jurisdiction to review such state decisions.”

Sometimes, civil rights lawyers will have no choice but to go to federal court. But under this ultraconservative Supreme Court, when they do have a choice of venue, they should think hard about it.