This article is published as a collaboration between Balls & Strikes and Bolts.

Left-leaning lawyers confront a daunting future in America’s new Gilded Age. Federal courts are firmly under conservative control, allowing the right to entrench existing racial, gender, and economic hierarchies. No left-wing judicial recruiting system exists that can match the reach of the right’s Federalist Society. And the left lacks a succinct progressive legal philosophy that can challenge the dominance of the conservatives’ textualism and originalism.

America faced these problems more than a century ago, too, when legal power was in the hands of reactionary federal courts that proudly championed plutocracy, segregation, and gender discrimination. During this period, known as the Lochner Era after one infamous decision, the Supreme Court invalidated child-labor bans, minimum wage laws, sixty-hour work week caps, and union protections.

Faced with this forbidding reality, legal reformers turned to state courts to fight back. Many of the era’s most prominent reformers—the white, male, upper-middle-class ones—largely ignored segregation and gender discrimination. But by working through state courts, particularly in Washington state, some of these reformers articulated a popular, widely-understood legal philosophy that rejected the dominant conservative philosophy of the day. Reformers then used this philosophy—legal realism—to champion workers’ rights, challenge the pro-corporate bias of federal courts, create a strong progressive legal bench, and lay the legal foundation for the New Deal.

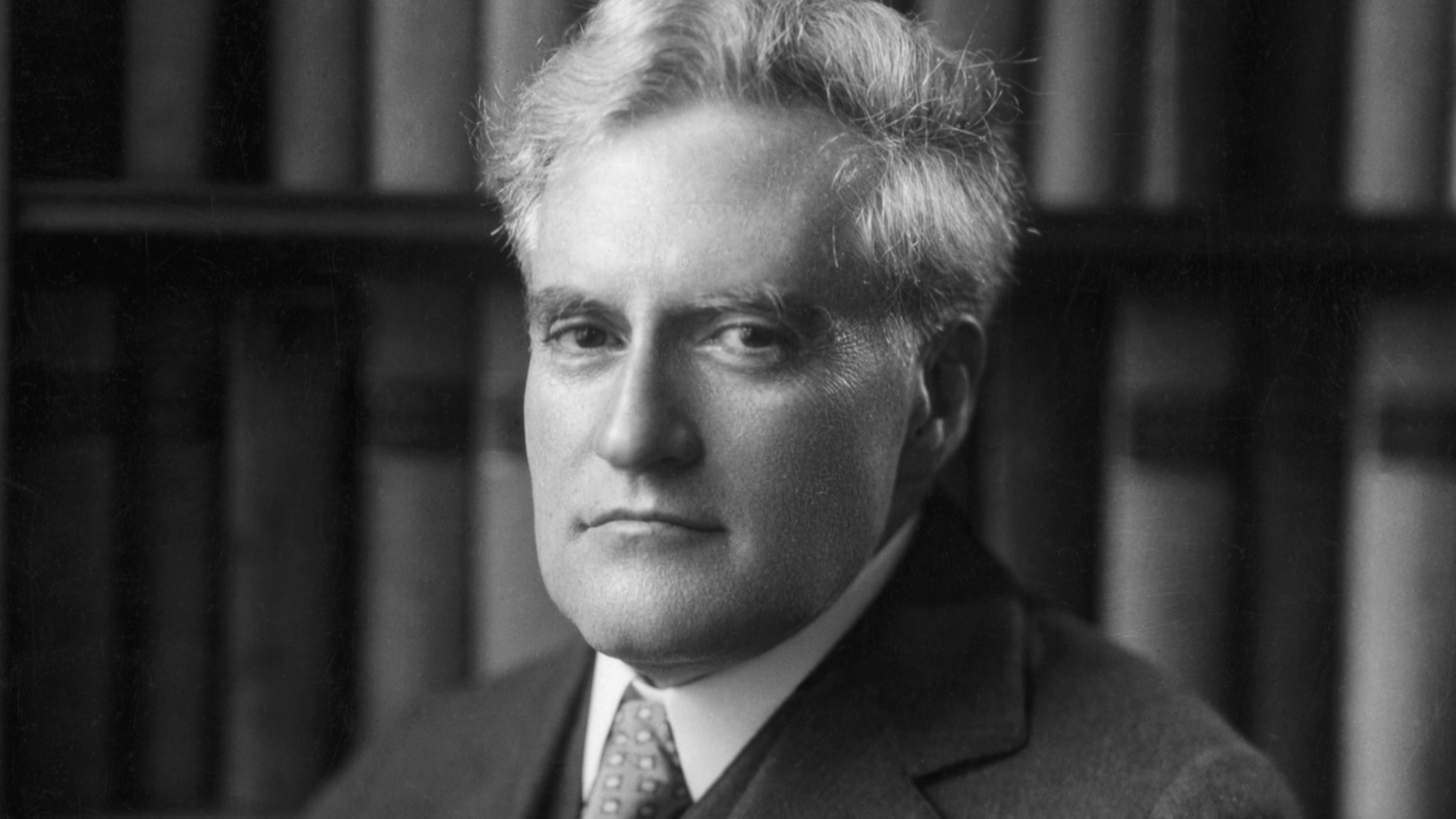

This is a picture of Benjamin Cardozo, NOT Bradley Whitford in a wig (Bettmann / Getty Images)

Today, there are hints that some progressives are turning toward state courts, particularly as the end of Roe v. Wade elevates state constitutions and courts to the forefront of the struggle for abortion access. But even at the state court level, left-leaning lawyers have made few attempts to lay the foundation for a popular alternative to conservative legal philosophy.

During the first Gilded Age, legal reformers developed their big idea to counter the technical, abstract approach used by their conservative contemporaries, the formalists. The two sides had different ideas about the kinds of information judges should consider: Formalists, much like today’s originalists and textualists, claimed that judges should base their decisions on neutral legal principles and on America’s history—or at least a fictional vision of that history. And much like today’s originalists, the Lochner Court repeatedly found that ostensibly neutral principles and traditions—particularly the freedom to contract—prohibited a wide variety of popular legislation intended to protect workers.

Legal realists pushed back. They were led by Oliver Wendell Holmes and Benjamin Cardozo, both of whom sat on state courts before eventually joining the U.S. Supreme Court. As chief justices of the Massachusetts and New York high courts, respectively, Holmes and Cardozo argued that the law was not a set of timeless, neutral principles, but a product of economic, social, and political realities. Joined by like-minded realists, they made the case that American judges needed to adjust to new problems created by staggering change: railroads, urbanization, mass production, mass media, and so on. They wanted courts to permit elected legislators to use broad police powers to mitigate crises created by rapid economic change, from grisly workplace accidents to violent labor conflicts.

Cardozo, in particular, was that rare combination of state court judge and enthusiastic ideological evangelist. While serving on New York’s highest appellate court, he wrote an influential book, The Nature of the Judicial Process, in which he drew on Holmes’s opinions to argue that judges did not—and should not—decide cases by consulting “pre-established truths of universal and inflexible validity.” Doing so, he argued, would cause courts to make serious mistakes “not from misunderstanding of the law, but from misunderstanding of the facts.”

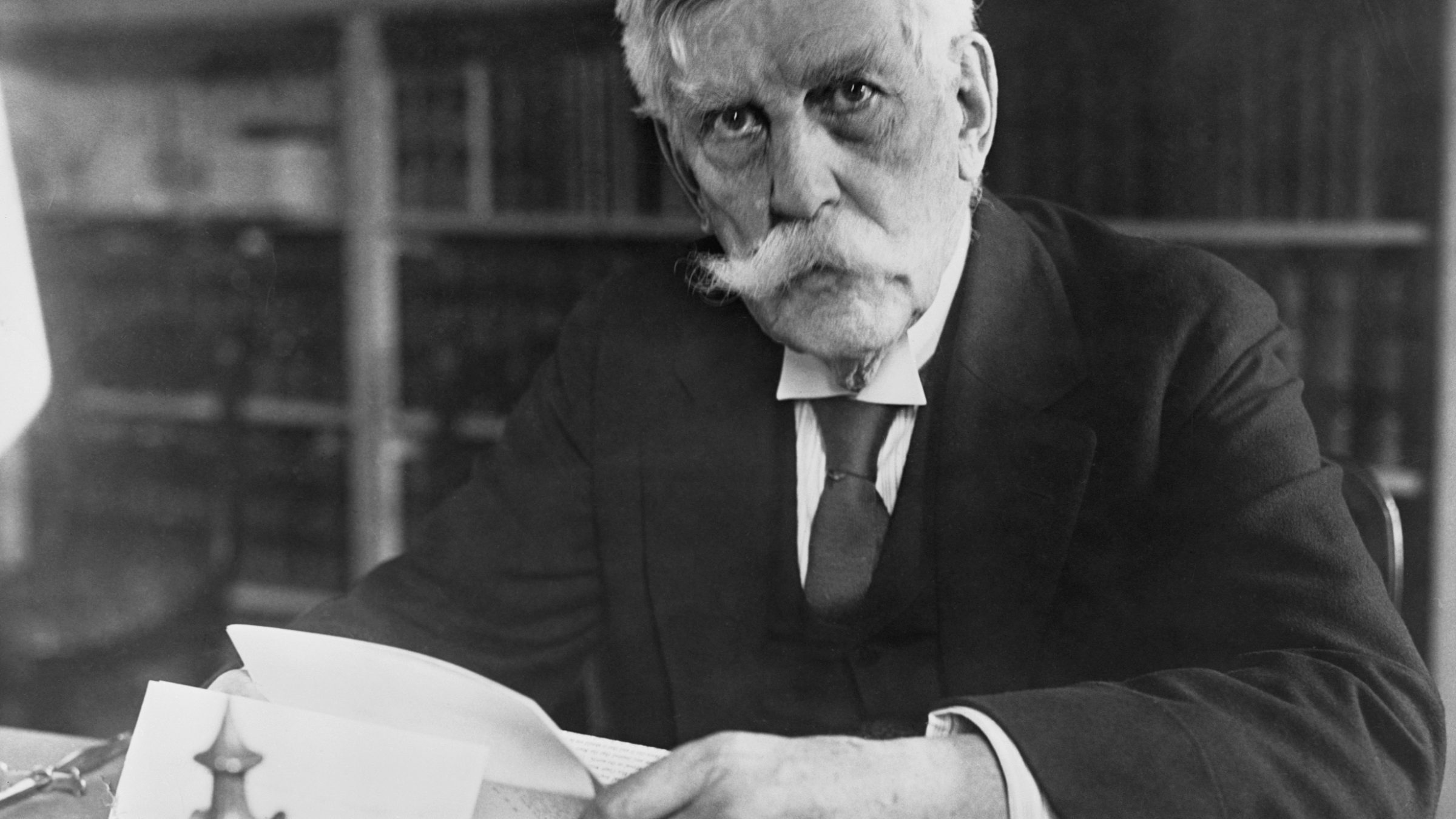

BACK: Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.; FRONT Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.’s mustache (Bettmann / Getty Images)

As an example of these mistakes, Cardozo pointed to a formalist opinion—People v. Williams—issued by New York’s highest court while Cardozo was still serving as a state appeals court judge. In that case, the court had invalidated a statute banning night work by women. According to Cardozo, the court’s mistake was ignoring the obvious social realities that made the law necessary: Judges, he argued, had to decide cases by testing “working hypotheses” and generalizing from hard-won experience. Cardozo later put his philosophy into practice, reversing People v. Williams on the grounds that “fuller knowledge of the investigations of social workers” had illustrated the need to protect women in the workplace.

Cardozo and other East Coast legal realists enjoyed a few victories, but reformers were most successful in Washington state. On its Supreme Court, a rotating cast of elected justices, many of whom had immigrated from more conservative eastern jurisdictions or more cautiously progressive midwestern ones, went on a reform spree. Between 1900 and 1937, the court, which President Theodore Roosevelt once described as the “most progressive court in the United States,” upheld a broad spectrum of state laws that were disfavored under the federal Supreme Court’s Lochner-esque precedents. These included laws reducing hours for women workers, creating an eight-hour day for public works employees, implementing a worker’s compensation program, creating a state commission to regulate railroads, and establishing minimum wages for public-sector employees, women, and children.

The court’s reformist streak began with court packing. In 1901, the legislature expanded the number of justices from five to seven for a two-year period, allowing Washington’s populist governor to nominate a pair of reform-minded judges who formed the backbone of an energetic progressive majority. The next year, in Green v. Western American Company, the court recognized that a miner maimed by his employer needed compensation, not empty platitudes about precedent. And in State v. Buchanan, it unanimously upheld a law limiting women’s workdays to 10 hours.

In Buchanan, Justice Ralph Dunbar explicitly rejected formalist legal principles like the absolute freedom to contract. Instead, he argued that courts had the “duty” in light of society’s “changing conditions” to uphold laws that protected the public from powerful corporations. The logic behind Buchanan proved so powerful that even the conservative U.S. Supreme Court, citing Buchanan, unanimously upheld a similar Oregon law seven years later.

The Buchanan decision and others building on it were so popular that Washington state reformers were able to outlast backlashes from both local conservatives and the federal judiciary. A newly-elected conservative governor’s 1905 attempt to re-pack the court with two pro-corporate judges failed. Conservative federal courts also failed to rein in Washington’s reformers. In a characteristic display of realist stubbornness, state Supreme Court Justice “War Horse Bill” White, responding to a federal judge’s criticism of a 1905 pro-union ruling, admitted that the ruling was probably incorrect under formalist precedents before declaring that Washington state would “stay wrong.”

Federal courts found themselves surprisingly powerless to respond: Limited caseloads ensured that that federal judges could only review a tiny fraction of relevant cases, enabling reformers to overcome the occasional reversal. Even a 1916 U.S. Supreme Court decision reversing a Washington Supreme Court opinion outlawing predatory employment agencies did little to deter Washington state reformers, who ultimately had the last laugh: The Lochner Era ended in 1937 when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a minimum wage law adopted by Washington’s state legislature. Cardozo, the evangelist of legal realism, was in the majority.

The Washington Supreme Court conducts oral argument via Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic, April 2020 (Photo via Washington Courts)

Today, the Washington Supreme Court is again among the more progressive state high courts, buoyed by a far more diverse set of judicial appointments than is common even in blue states. In a pair of landmark rulings in 2020, it issued new protections from extreme sentences and struck down state statutes criminalizing drug possession. (Democratic lawmakers partly walked back the second ruling.)

However, the court has yet to articulate an overarching legal philosophy underpinning these rulings, even though its opinions continually prioritize social, economic, and political realities over abstract legal principles. The justices also often ground their opinions in Washington’s own constitution. This shields these rulings from hostile federal judges; it also sidesteps criticism of federal jurisprudence and inhibits the development of a clear alternative philosophy.

Such caution is understandable. Washington state’s justices may worry that Cardozo-style evangelism would further politicize the legal system and that, as they did in the early 20th century, conservative federal judges may retaliate against any nascent left-wing legal reform movement. Already, the U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear a case next term that will test the independent state legislature doctrine, which would kneecap the authority of state courts over key matters of election law.

Washington’s Lochner Era experience may still provide today’s reformers with a way forward, one in which state courts can expose the public to new legal philosophies that allow judges to take the world as it is. In an era when the U.S. Supreme Court’s “correct” jurisprudence denies basic rights to millions of people, War Horse Bill’s immortal advice for state courts remains largely unheard: “Stay wrong.”