Last year, President Joe Biden announced a plan to forgive up to $20,000 in student debt for some 43 million borrowers whose lives and livelihoods were upended by the COVID-19 pandemic. On Tuesday, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in two cases that will together determine whether he is allowed to go through with it. Nothing encapsulates this country’s fundamental brokenness quite like the obligation to beg nine life-tenured justices who earn quarter-million-plus dollars a year for permission to make the debt burdens of working people marginally less crushing.

For longer than I’ve been alive, the conservative legal movement has coalesced around what I would describe as a jurisprudence of fuck-your-feelings. In this conception of the constitutional order, judges are not to behave as “activists” who concern themselves with fuzzy concepts like “equity” (whatever that means) or doing “justice” (same). Instead, they are to set aside their policy preferences and apply the law as written, no matter where the analysis takes them. To borrow a metaphor with which readers of this site are familiar: Properly understood, a judge’s job is to call balls and strikes, not to pitch or bat.

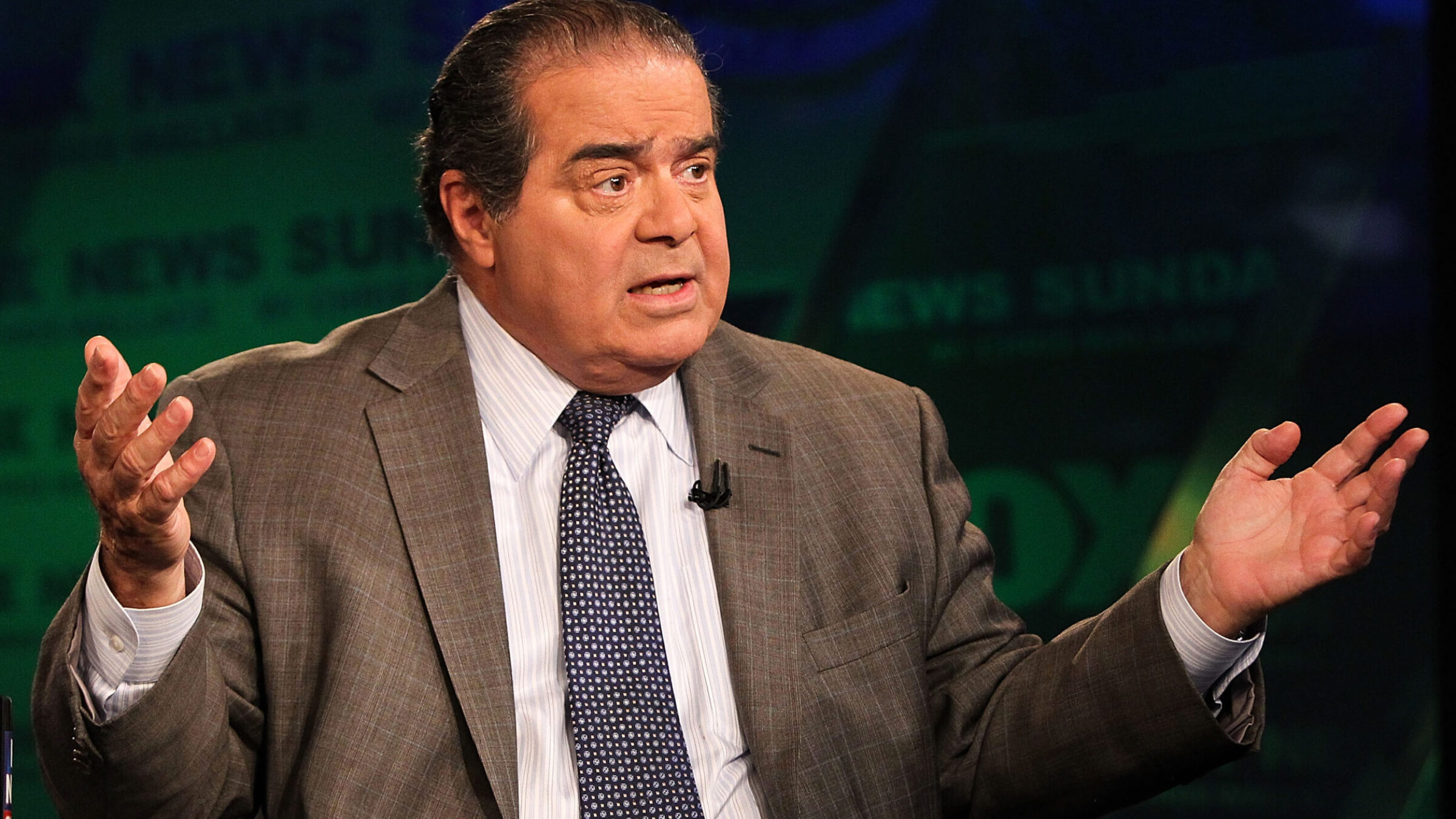

“Textualism means you are governed by the text. That’s the only thing that is relevant to your decision,” the late Justice Antonin Scalia told Fox News’s Chris Wallace in 2012. “Not whether the outcome is desirable, not whether legislative history says this or that. But the text of the statute.”

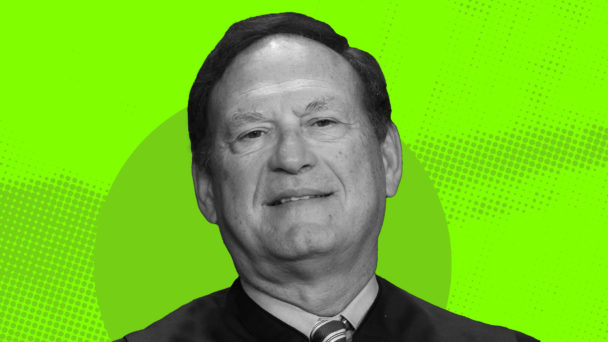

When someone asks you what the legislative history reveals about a statute’s purpose (Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images)

For this reason, it was more than a little startling to hear conservative justices spend their time on Tuesday fixated on a point that will be familiar to anyone with children who are old enough to talk. The legal authority for Biden’s plan is a 20-year-old federal statute that allows the Secretary of Education to “waive or modify” student debt obligations for borrowers affected by a national emergency. The statute’s text is neither complicated nor ambiguous. To anyone without a terminal case of Federalist Society brain, its relevance to an economic crisis stemming from a global health disaster that has dragged on for three years and counting does not require detailed explanation.

And yet, the conservative justices argued, there remains a fundamental problem with Biden’s plan: It just isn’t fair to those who would not benefit from it.

“I think it’s appropriate to consider some of the fairness arguments,” announced Chief Justice John Roberts, who posed an elaborate hypothetical about two high school graduates: one who borrows money to go to college, and the other who borrows money to start a lawn care business. The Biden plan, he argued, provides nothing to the businessman and yet forces him to subsidize the student. “Why isn’t that a factor that should enter into our consideration?” asked Roberts, apparently unable to fathom a more sympathetic debt-saddled person in America in 2023 than a guy who owns a business.

When someone takes your toy at recess (Photo by Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images)

Roberts was not the only conservative justice with a newfound passion for freelance justice-doing. Justice Neil Gorsuch asked Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar whether the government had accounted for “costs to other persons in terms of fairness—for example, people who have paid their loans, or who plan their lives around not seeking loans, or people who are not eligible for loans in the first place?” Benefits programs create “winners and losers,” argued Justice Brett Kavanaugh, which raises “concerns” about “individual rights.” At least three times, Justice Samuel Alito demanded that Prelogar explain why the plan is “fair,” and accused her of dodging the question when she failed to answer to his satisfaction. For a movement that purports to focus on esoteric legal questions, the conservatives sure are quick to get philosophical whenever they feel aggrieved by the result.

Collectively, Prelogar and the liberal justices had a simple answer: An act of Congress need not be “fair,” in the colloquial, kindergartners-at-recess sense, in order to be legal. As Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pointed out, a benefit program, whether occasioned by war or natural disaster or a once-in-a-generation pandemic, cannot be invalid just because the powers that be decided that fewer than literally 100 percent of people can take advantage of it. Targeted financial subsidies and loan forgiveness programs are hardly new. Even in the context of COVID-19, the government has forgiven hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of loans it issued to keep struggling businesses (including landscaping firms) afloat during the pandemic. If Roberts harbors similar concerns about whether this 12-figure handout is fair to students who were ineligible to take part in it, he did not express them on Tuesday.

“There’s inherent unfairness in society, because we’re not a society of unlimited resources,” explained Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in an oblique rebuke of Alito disguised as a rhetorical question for Prelogar. “Every law has people who encompass it or people outside it. That’s not an issue of ‘fairness.’ It’s an issue of what the law protects or doesn’t.” Or, as Justice Elena Kagan put it in a more direct rebuttal to Roberts’s case of the luckless landscaper: “Congress passed a statute that dealt with loan repayment for colleges. It didn’t pass a statute that dealt with loan repayment for lawn businesses.”

Politics involves hard choices, and every choice will feel unjust to those who do not benefit from it. But the myopic obsession with equity here, in this one case, lays bare the intellectual bankruptcy of a conservative legal movement that has spent half a century rhapsodizing about how judges must apply the law, not make it. Just last year, all six conservatives agreed that Congress’s choice to make millions of people in Puerto Rico ineligible for certain federal disability benefits presents no fairness concerns that require judicial intervention. Today, confronted with an application of a statute that leads to a result they don’t like—a Democratic president fulfilling a popular campaign promise—the conservatives are proposing to reserve the option to veto any executive action they deem Too Big A Deal.

(Photo by Sarah Silbiger for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

One conservative legal movement superstar who would have been unimpressed by John Roberts’s histrionics on Tuesday is John Roberts four years ago, who wrote the majority opinion in Rucho v. Common Cause that declared federal judges powerless to stop lawmakers from gerrymandering themselves into power in perpetuity. Rucho, which the Court decided in 2019, dismisses a judge’s obligation to center “fairness” in his or her analysis. Sorting through the term’s competing conceptions, Roberts wrote, “poses basic questions that are political, not legal.” He concluded: “Any judicial decision on what is ‘fair’ in this context would be an ‘unmoored determination’ of the sort characteristic of a political question beyond the competence of the federal courts.”

The point here is not that any given outcome in any given case is objectively right or wrong. The point is that every outcome in every case is a value judgment that reflects the politics, preferences, biases, and beliefs of the black-robed superlegislators who make it. The work of a judge is not to set aside appeals to fairness when answering legal questions. It is to decide whose appeals to fairness matter, and when, and how much.

For all the attention paid to the theoretical plight of hypothetical small business owners on Tuesday, it was easy to forget the real, tangible people whose financial futures actually hang in the balance right now—people who probably have thoughts of their own about what is fair and what is not. “There are 50 million students who will benefit from this,” Sotomayor said. “Many of them don’t have assets sufficient to bail them out after the pandemic. They don’t have friends or families or others who can help them make these payments.” Absent government intervention, she concluded, “they are going to continue to suffer.”

The six members of the Court’s conservative supermajority have spent their careers proudly not giving a shit about fairness for anyone who is not a corporation or a Republican politician charged with a slew of campaign finance violations. If they indeed have the votes to declare Biden’s plan too unfair to be legal, that result will be no less unfair. It will just be a political choice to tolerate unfairness to people the conservative justices don’t think should count.