The worst time of year is almost here. The Supreme Court’s term usually ends by late June or early July, which means that in the next few weeks, the justices will begin handing down their blockbuster bad opinions—which, this year, could include protecting racial gerrymanders, cutting off access to abortion medication, and giving Donald Trump a free pass for crimes.

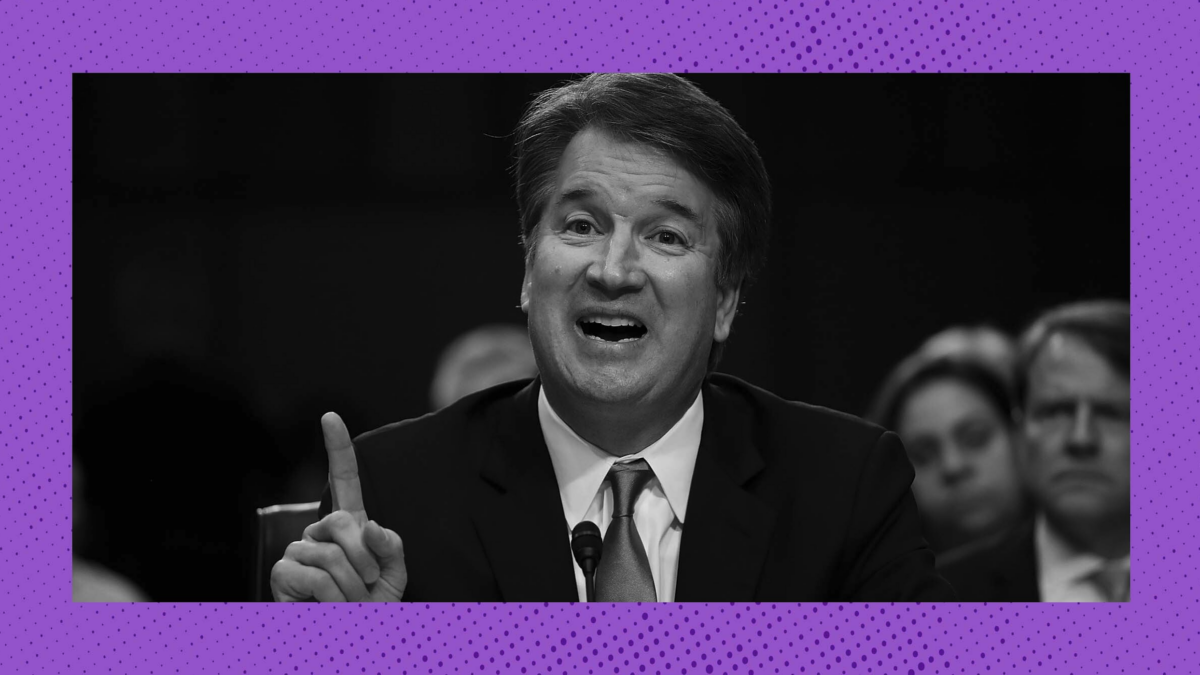

Brett Kavanaugh is trying to get out ahead of the coming public outrage. Last Friday, the justice attended a conference in Austin, Texas, for the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals—the origin point of many of the Court’s bad decisions—where he sat for an interview with the Circuit’s chief judge, Priscilla Richman. In this interview, Kavanaugh argued that unpopular Supreme Court decisions aren’t necessarily bad—and suggested that their unpopularity may be evidence that they are good and correct.

Kavanaugh specifically highlighted some of the landmark Supreme Court cases from Earl Warren’s tenure as chief justice: Brown v. Board of Education, the school desegregation case, which only 53 percent of the public approved of when it was decided in 1954, and Miranda v. Arizona, the 1966 case that obligated police to warn suspects of their constitutional rights, and that Richard Nixon used to fuel his successful presidential campaign two years later. According to Kavanaugh, decisions like these made the Warren Court “unpopular basically from start to finish.” But, he said, many of those “unpopular” decisions are “landmarks now that we accept as parts of the fabric of America, and the fabric of American constitutional law.”

The implication here is that perhaps this Supreme Court, which needed just three years’ worth of a six-justice conservative supermajority to reverse longstanding protections for affirmative action and end the right to abortion care, is not behaving in a way that is so unusual, after all. Perhaps it’s fine that the Court’s approval ratings are embarrassingly low! (Last month, its approval creeped up to its highest level in over a year: all of 47 percent.) After all, what’s right isn’t always popular, and what’s popular isn’t always right.

But Kavanaugh’s statement elides that the Supreme Court is fully capable of being both wrong and unpopular. The conservative legal movement never accepted the rulings of the Warren Court, and conservative justices have spent decades hollowing out many of that era’s landmark decisions, including both Brown and Miranda. Kavanaugh’s invocation of the legacy of those rulings obscures the fact that they have nothing in common with the rulings the Court is making today: Warren Court decisions were unpopular because they reinforced the rights of marginalized people. The Roberts Court’s decisions are unpopular because they reinforce marginalization itself.

To this day, Republican judicial appointees regularly refuse to say Brown was correctly decided. Yet the conservative justices can’t keep Brown out of their mouths when it suits their purposes. Justice Samuel Alito cited Brown in his opinion overturning Roe v. Wade to support the idea that “extraneous influences” like “the public’s reaction” cannot be allowed to affect the Court’s decisions. Kavanaugh cited Brown in his concurrence, too, as evidence that the Court is authorized to overturn “egregiously wrong” precedent. These conservative justices are trying to cloak themselves in the trappings of Brown to hide the fact that their controversial decisions are much more like Dred Scott, and regular people are reacting to the Court’s campaigns of dehumanization and subordination accordingly.

Kavanaugh’s appeal to Warren Court decisions that became part of the “fabric of America” obscures the fact that the Roberts Court has been instrumental in unraveling it. And as much as he might want Dobbs to be on the same plane as cases like Brown, no one outside of his Federalist Society circles is buying it: Since the Court decided Dobbs in 2022, anti-choice activists have taken loss after loss at the polls, as voters make abundantly clear that they do not like or trust the Supreme Court, and want it to stop. Brett Kavanaugh’s mewling false equivalences are not going to change that.