I regret to inform you that Stephen Breyer is at again. Two years after a thunderous cyberbullying campaign ended with his resignation from the Supreme Court, the 85-year-old former justice has released yet another book, Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, Not Textualism, to explain his approach to serving as a justice and judge and interpreting the law.

This is not the first time Breyer has opined on the topic. Nearly twenty years ago he published Active Liberty, which provided an initial exploration of his constitutional philosophy. More recently and notoriously, Breyer released The Authority of the Court and the Peril of Politics while he was still a sitting justice. That book—really a pamphlet—received scathing criticism for its unsophisticated arguments claiming that the Supreme Court does not function as a political institution. Luckily, Breyer announced his resignation shortly thereafter, ensuring that unlike certain other recent justices, he would exercise some control over who followed in his seat.

Why, then, go back to the well? As Breyer put it to The New York Times’s Adam Liptak: “Something important is going on.” Belatedly, tentatively, and long after the horses have left the barn, Breyer warns Liptak’s readers that the Court has taken a proverbial wrong turn. Sir, I regret to inform you that this melodrama started about fifty years ago, and you’ve arrived in time to only catch the tragic ending.

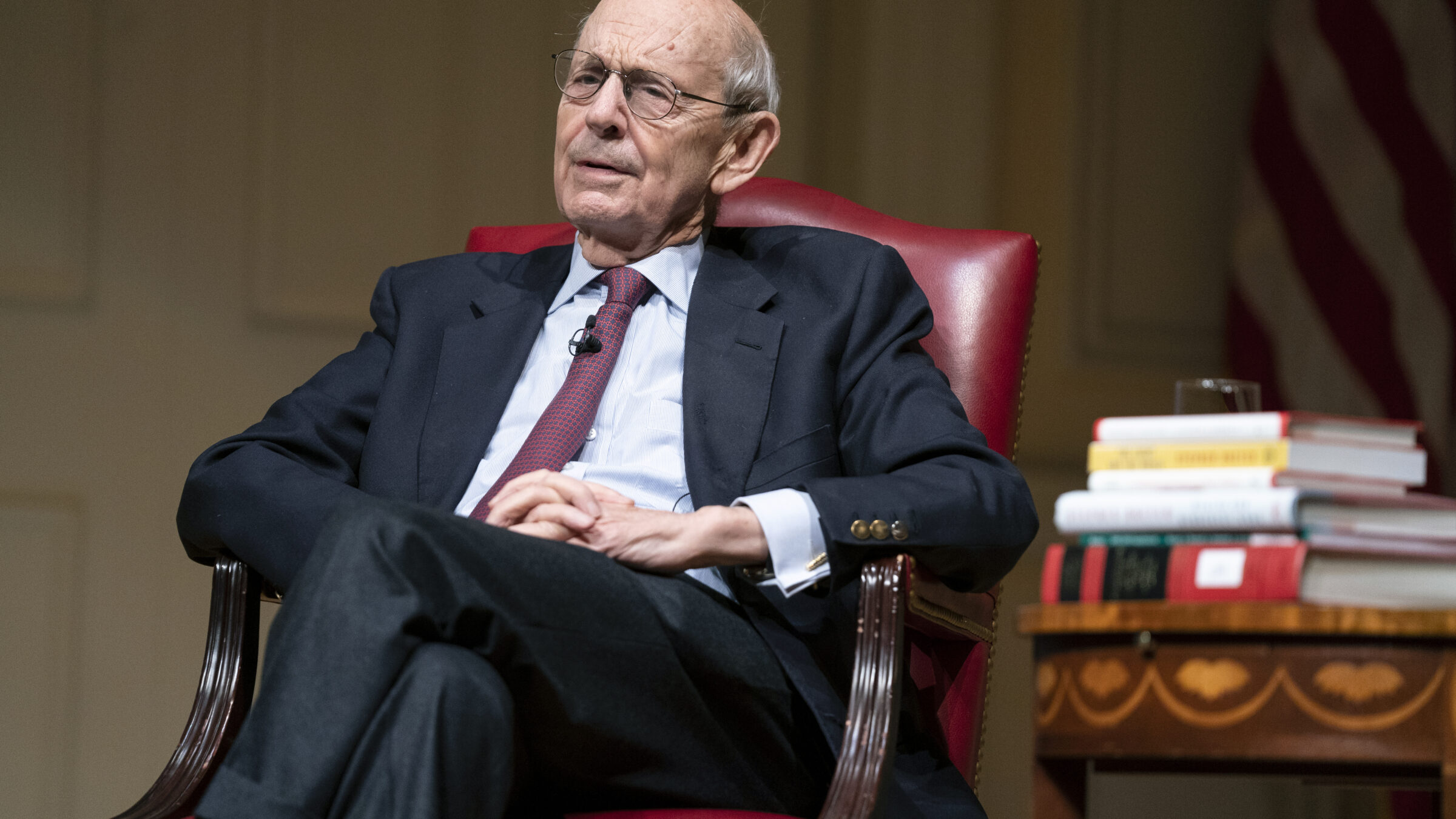

(Photo by Evan Vucci-Pool/Getty Images)

I remain confused that Breyer chose to let loose, relatively speaking, to the Times while maintaining a mannered placidity in his own book. Breyer has nothing to lose—he’s off the bench and back in the academy, teaching debt-ridden law students about something we once had in this country called “administrative agencies.” Early in the book, he argues that “the many promises of textualism and originalism often are not, or cannot be, realized,” and promises an alternative—an affirmative vision of “legal interpretation as an activity that is basically pragmatic, undogmatic, and adaptive.”

So far, so good—we desperately need more high-profile liberal judges, academics, and activists to set forth a vision that refuses to concede to the framing peddled by the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority. After finishing the book, I can attest that anyone who reads more than a few pages will quickly realize that Stephen Breyer cannot inspire.

Reading the Constitution symbolizes so starkly why liberal justices and judges so often fail to meet the moment. With over forty years of judicial service and fifteen years on the Harvard Law faculty, Breyer remains a creature of the legal elite. He cannot bring a lawyer’s tactics, zeal, or passion to his arguments; he instead prefers a bloodless, technocratic, and abstract judicial register that sees principles, not people.

The book’s structure belies this tendency. Breyer claims that Reading the Constitution will justify his anti-textualist approach to judging, which incorporates “purposes, consequences, and values.” But his exploration of his philosophy does not begin with high-profile constitutional or statutory cases from his time on the Court, like Dobbs (the end of the right to abortion care), or Bruen (the expansion of the right to gun possession), or the student loan forgiveness cases (laws don’t mean what they say). Those cases would have provided too interesting or too provocative opening arguments. No, instead Breyer chooses to begin with his 2020 majority opinion in County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund, a case I had never heard of, and bet you hadn’t either. The question, in Breyer’s words: “Does [a] sewage plant need an EPA ‘permit’ in order discharge the sewage into the ocean, a ‘navigable water’”? An important environmental question, yes, but hardly a generational call to arms.

Lawyers know that if you want to convince your audience, you have to rouse them. This book repeatedly refuses to try. Instead, Breyer writes like the former and present Harvard Law professor he is. I am one of those weird people who found administrative law riveting as a student, but even I found the book’s early chapters dull, full of applications of his purposive philosophy to interpreting statutes. Return Mail v. United States Postal Service; Jam v. International Finance Corp.; Wisconsin Central Ltd. v. United States—these are not the Supreme Court cases you lead with to persuade a reader to embrace your approach to judging, let alone generate enthusiasm for it.

(Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

You might think things would pick up when, more than 100 pages in, Breyer finally gets to the “Interpreting the Constitution” section. Sadly, this portion of the book is as compelling as his attempts to persuade his conservative colleagues during his last years on the bench. It’s not that his descriptions of Bruen, the OSHA vaccine mandate case, or Dobbs are wrong or misguided. I generally agree with his positions. But his analysis is bloodless and boring. In his view, for example, the aspect of Dobbs most warranting discussion is the stare decisis question: whether and when the Court should overrule its own precedent. That’s an important part of any critique of Dobbs, but absent from his narrative is a discussion of the inherently political nature of the case and its path to the Court. When Dobbs was argued, Justice Sonia Sotomayor referred to the “stench” that would waft from the Court if and when Roe fell. But Breyer declines, even with the most egregious cases, to similarly move the spirit of the reader.

One expects more of an experienced legal educator. Having taught for nearly a decade, I’ve learned that I succeed when I make my students care. The best way to do that? Emphasize the stakes. But Breyer imparts no sense of the stakes of a world without meaningful reproductive justice, in which pregnant people face the prospects of criminalization, illness, or death for attempting to exercise their rights. No idea of what it means for a society without effective gun safety laws, where elementary school children go through active-shooter lockdown drills and anyone walking into a big box store has to wonder if they’ll walk out of it. No discussion of how the Court’s gutting of the Voting Rights Act and tacit endorsement of partisan gerrymandering has eroded any chance of the United States functioning as a pluralistic democracy. Instead, we get enervating descriptions of stare decisis and academic critiques of the conservative supermajority’s selective invocations of history and tradition. Breyer has literally brought constitutional theory to a gun rights fight.

This propensity for recasting fights over the fate of the nation as esoteric legal debates betrays the fact that Breyer has left the Court only in title. Throughout, he seems incapable of giving up the “we all adore each other” vibe that most Supreme Court justices prefer to peddle. For example, he assures us that he was good friends with Justice Antonin Scalia; did you know they “loved our Court sing-alongs using Chief Justice Rehnquist’s Old Time Songbook”? What a relief that Bush v. Gore didn’t destroy the joys of off-key harmonizing at One First Street.

Even if you think it’s worthwhile to befriend your adversaries, Breyer takes it a step further. He constantly refers to his “textualist colleagues” rather than ever hint at criticism of their reactionary politics, and notes, with a sense of relief, that the public could see his disagreements with Scalia were done in “a civil manner.” He either cannot admit or does not realize that these debates have meaningful consequences for millions of Americans and threaten fundamental aspects of democratic structures.

Breyer must know that alternative strategies exist. Some of his colleagues realize that you prevail over your ideological opponents both at the bench and in the court of public opinion: Perhaps most notably, Scalia persuaded a substantial swath of Americans that originalism made sense not just through his majorities and dissents, but also through a PR tour that lasted decades. It’s bad enough that Breyer, given his academic tendencies, would be probably one of the worst emissaries for his philosophy. What’s worse is that he doesn’t seem to realize that such a push is necessary in the first place.

WATCH: Former Supreme Court Justice Breyer tells #MTP that people in the U.S. have lost the ability to listen.

Pointing to a copy of the Constitution, he says, “This is, in part, the United States of America. … Maybe we’re not listening to as much as we should.” pic.twitter.com/T0tHaE6JFO

— Meet the Press (@MeetThePress) March 24, 2024

Progressives have few vocal allies on the bench who speak out in favor of a legal vision that supports the vulnerable and furthers a pluralistic democracy. Even the sitting liberal justices too frequently resort to delusions of bonhomie that downplay the consequences of their legalistic decisions. We need better, more shrewd justices and judges on our side, not those who think they can win with clever legal arguments alone. Indeed, Reading the Constitution fails because it refuses to meet Breyer’s goal of providing an energizing response to the dominance of the conservative legal movement’s judicial strategy.

In retrospect, the book’s shortcomings are apparent from before it begins. He dedicates Reading the Constitution to each of the justices with whom he served, individually and on a first-name basis, beginning with William Rehnquist, who as a law clerk was famously skeptical of Brown v. Board of Education, and ending with Amy Coney Barrett, whose vote killed Roe once and for all shortly before Breyer left the bench. Even in retirement—when Breyer has no votes to win or lose, and the prominence and freedom to inspire a new generation of justices, judges, and lawyers—he’d still rather have his fifteen friends, the living and the dead.