Editor’s note: This month, we’ll be taking a closer look at some of the most consequential cases the Supreme Court—the most conservative Supreme Court in a century—will decide in its upcoming term. Today: Brackeen v. Haaland, which the conservative lawyers and well-heeled corporations that have been chipping away at Tribal sovereignty hope will just get rid of Tribal sovereignty altogether.

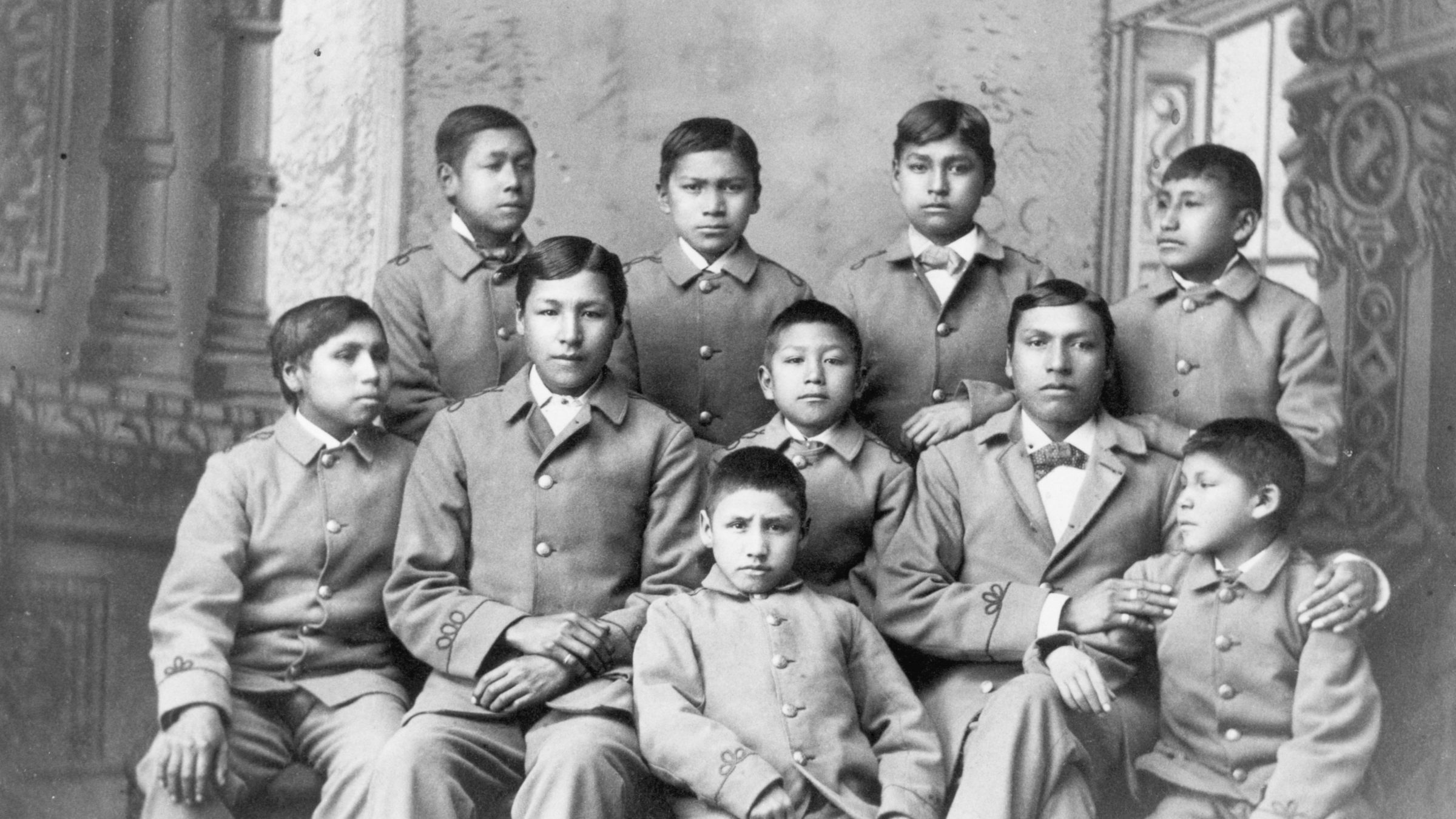

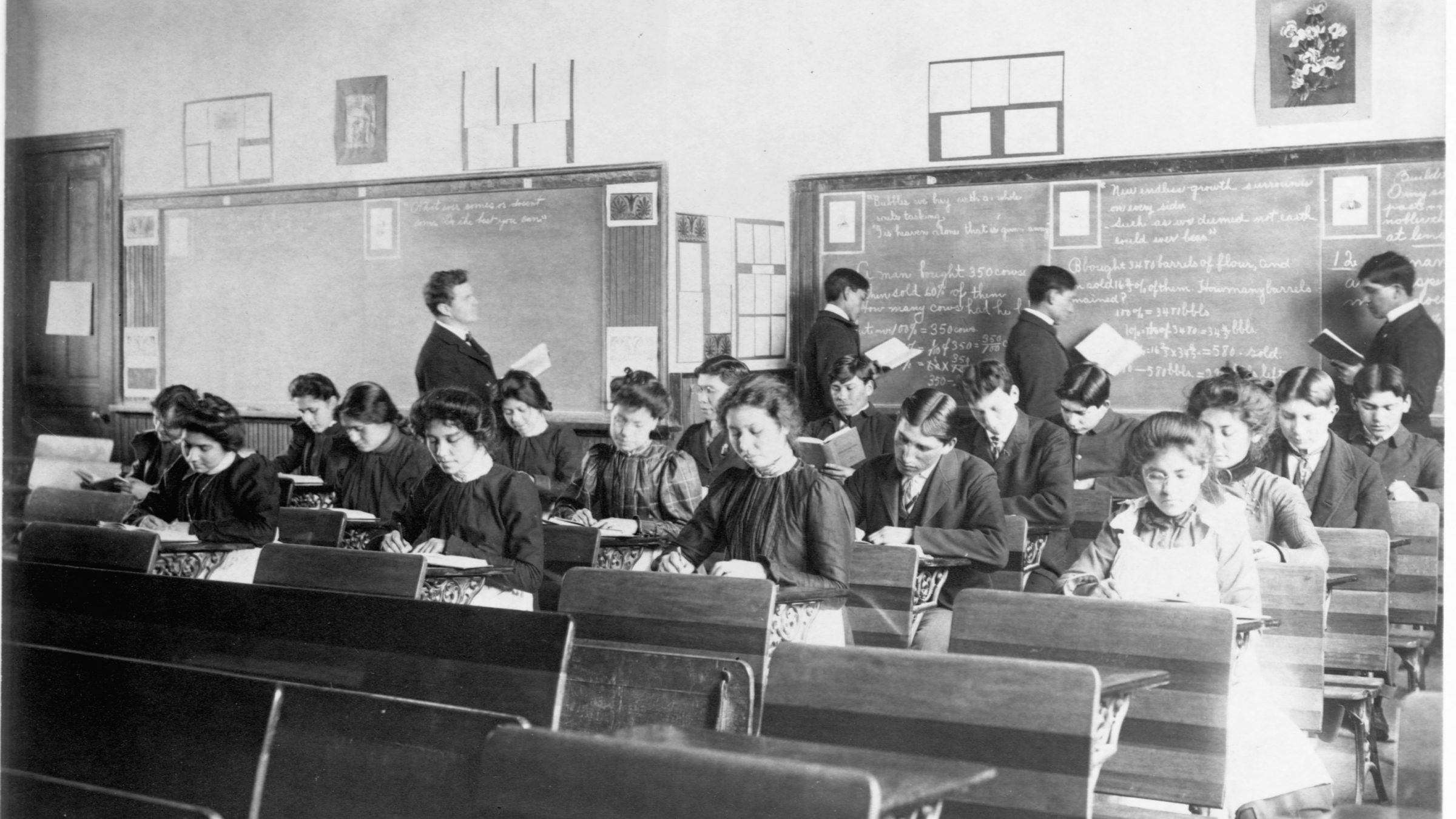

Long before President Donald Trump’s nightmarish immigration policy made the phrase famous, a different family separation epidemic was underway: In the mid-20th century, private adoption organizations and public welfare agencies were removing roughly one-third of Native children from their homes pursuant to a federal initiative known as the Indian Adoption Project, placing children in foster care, with adoptive families, or in institutions instead. Before that, the government sent Native children to special boarding schools formed for the purpose of assimilating Native children—schools that were rife with “rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse.” Hundreds of children died in the custody of a state that claimed to be acting in their best interests.

In 1978, Congress responded by passing the Indian Child Welfare Act with the goal of “promoting the stability and security of Indian tribes.” The ICWA creates procedural safeguards in child welfare proceedings that prioritize kinship placements: When a child will be removed from their home, whether temporarily or permanently, the law gives preference to extended family members, members of the parents’ Tribal nation, or any Native family. Only after examining these placement options can an agency place a Native child with a non-Native family.

Chad and Jennifer Brackeen want to change all this. They are are challenging the ICWA in federal court, arguing (among other things) that it violates the Equal Protection Clause by creating impermissible racial classifications. The Supreme Court’s forthcoming decision in Brackeen v. Haaland, in which the justices will hear oral argument in November, will have profound implications for the future of legislation aimed at preserving Tribal self-governance.

A group of Omaha Indian boys in cadet uniforms, Carlisle Indian School, Pennsylvania (Photograph by J. N. Choate, ca 1880. BPA 2 #3273 / Bettmann / Getty Images)

In 2016, the Brackeens fostered a Native child, A.L.M, for a little over a year. When a Texas state court terminated the parental rights of A.L.M’s biological parents, the Navajo Nation pushed to place him with an unrelated Native family; that arrangement ultimately didn’t pan out, clearing the way for the Brackeens to adopt A.L.M. after all.

Not content simply to win their case and go home, however, the Brackeens—suddenly backed by corporate lawyers whose Big Oil clients perhaps have a vested interest in the status of Tribal sovereignty—launched a legal challenge to the ICWA, claiming that it illegally commandeers states to carry out a federal policy, and that it discriminates against non-Native people during the adoption process. (Or, as Erin Dougherty Lynch, a senior staff attorney of the Native American Rights Fund who co-wrote an amicus brief in this case, puts it: “Their feelings were hurt.”) Now, they are asking the Court to declare ICWA unconstitutional because they want to adopt A.L.M’s younger sister, too, and claim the law will prevent them from doing so.

The intervening decades since the ICWA’s passage have not made it less relevant today. Native children are removed from their homes at 2-3 times the rate of non-Native children, according to the National Indian Child Welfare Organization. And as a coalition of child welfare organizations wrote in a recent amicus brief in a related Supreme Court case, the ICWA’s focus on the fit between family and child make it objectively good policy— the “gold standard for child welfare policies and practices that should be afforded to all children.” To understand more about what’s at stake in Brackeen, we spoke with Lynch and Daniel Lewerenz, a professor at the University of North Dakota School of Law and former staff attorney at NARF.

Balls & Strikes: What prompted Congress to pass the ICWA in the first place?

Daniel Lewerenz: There was a long history of states disregarding Tribes in child welfare proceedings. ICWA is meant to affirm the place of Tribes in decisions concerning their children because Tribes have jurisdiction over their members, including their children, both on- and off-reservation.

ICWA enacts minimum standards for state court proceedings to ensure that Indian children’s best interests are protected—things like notice to parents, so they can participate in child welfare proceedings, and notice to Tribes so that they can participate as well. ICWA contains evidentiary standards that make sure that state courts aren’t making decisions based on an insufficient understanding of Tribal families and Tribal communities, which include placement preferences for foster care and adoption. Indian children are first placed with family. When that’s not possible, they are placed within their Tribal community. And when that’s not possible, they are placed with other Indian families.

B&S: What parts of ICWA are being challenged in Brackeen?

Lewerenz: All of it. The plaintiffs argue that the ICWA creates impermissible racial classifications. For example, they point to the part of the law that defines “Indian child,” which includes some children who are not Tribal members, and argue that the definition must be racial because it goes beyond Tribal membership. They also argue that ICWA’s preference for “any Indian family” is a racialized preference because it is not limited to the child’s Tribe.

What they’re really doing is making a much broader challenge to all of Indian law by saying, “This is racial,” as opposed to the political understanding that Congress and the courts have shared for the last 200-plus years.

The definitive case on this question is Morton v. Mancari. In it, the Supreme Court says that if an act of Congress is directed at fulfilling Congress’s unique obligation to Indians, then that is a political distinction, not a racial one, and the Court shouldn’t disturb that law. The Court also says that when the law at issue is directed at advancing tribal self-governance, that threshold is easily met. But if you read Texas’s brief, they actually stitch together sentences from Mancari like Dr. Frankenstein to say that because ICWA is not about tribal self-governance, it does not meet the Mancari standard.

The Brackeens argue that the placement preference for “any Indian family” moves beyond Tribal self-governance. In doing so, they artificially narrow Tribal nations’ relationship to the federal government in a way that Congress never intended. There are Tribes, for example, that were split for purposes of federal recognition. One easy example is that there are three federally-recognized Cherokee Tribes: the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, and the United Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma. A child who is a member of one of those Tribes, presumably, is not a member of either of the other two. Technically, a placement of a Cherokee Nation child with an Eastern Band family is not a placement within that child’s Tribe, but that doesn’t mean that it’s a placement with a family that is different culturally.

B&S: What are the possible outcomes here?

Lewerenz: If the Court were to narrow the field of Indian commerce so that it is coterminous with our understanding of interstate commerce, a lot of Indian law flies out the window. Congress has been legislating Indian affairs for more than 200 years, and that is never how Congress or the Court have understood congressional powers over Tribes.

If the Court were to broadly rule that ICWA is unconstitutional on Equal Protection grounds, almost 200 years of legislative history becomes really hard to justify. A variety of states have implemented all or parts of ICWA into their own state law. So if the Court holds that ICWA is unconstitutional because it’s based on race, those state law provisions will probably fail as well.

If the Court rules on anti-commandeering grounds, states that voluntarily enacted parts of ICWA into state law would not have an issue because they did so independently. But it would still be a terrible blow to Tribes and families, because a lot of states have not implemented all of ICWA. This would create a patchwork of rights in different states for Native children in welfare proceedings.

The Brackeens sit down with an interview with Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, seen here taking a rare break from his usual work of trying to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election (Clip via YouTube)

B&S: How are the Brackeens’ lawyers using the nondelegation doctrine in their argument?

Lewerenz: Nondelegation has gotten a lot of attention as a conservative theory for limiting executive power. It is almost always about legislation that one faction believes gives too much discretion to the executive branch and, as such, effectively cedes congressional power.

That is not at all what’s going on here. Section 1915(C) of ICWA says that if a Tribe has enacted its own placement preferences, state courts should follow them. The petitioners characterize this as a delegation to Tribes to rewrite federal law, which it absolutely is not. The only way I can rationalize them making this argument is that they believe they have a Court that is generally predisposed to nondelegation. They are hoping that if they put that buzzword out there, the justices will be too distracted, or too in favor of non-delegation generally, to actually think about the argument.

B&S: How does this challenge to the ICWA fit into the history of ICWA challenges?

Lewerenz: Until very recently, prior challenges arose somewhat organically. If someone was not happy with the way ICWA affected their case, they appealed through the state court system. Some of those cases were actually brought by non-Indian parents who thought that ICWA should apply to them because they saw that it afforded greater protections to parents. We often say that ICWA is the gold standard not just for Indian children, but for all children. We’d love it if states and Congress enacted it more broadly.

That was the case right up until Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, which came up through South Carolina state courts. Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote the opinion [in 2013], begins, “This case is about a little girl (Baby Girl) who is classified as an Indian because she is 1.2% (3/256) Cherokee.” That’s a strange way to start when that fact has nothing to do with the legal questions. Alito returns to that presentation of the facts later on, saying that if ICWA were to apply as a “racial statute,” he would have real Equal Protection concerns.

That is why we are here now, in Brackeen. Justice Clarence Thomas concurred in Adoptive Couple by raising concerns about the scope of congressional power in Indian affairs, and suggesting that ICWA may exceed that scope. Both of them were saying, “Here’s the case we want.”

Shortly after Adoptive Couple, we had the first challenge to ICWA brought by the same attorneys representing the National Council for Adoption in an amicus brief. The adoption industry—the people who make tens of thousands of dollars on each transaction—were trying to get the ICWA thrown out by making the arguments that Alito and Thomas were signaling their openness to. A second lawsuit was brought by the Goldwater Institute, also an amicus here.

The challengers lost both of those lawsuits. But this suit is a little bit different: There is a forum-shopping element to it. The Brackeens’ attorneys filed this case in front of a judge who has a history of invalidating federal statutes and embracing conservative causes. They also signed up Texas as a party to the lawsuit. That made a big difference, because it allowed them to make anti-commandeering arguments, which otherwise are pretty hard for a non-state party to assert. This is the first time that a state has brought not only an Equal Protection challenge to the ICWA, but has also embraced this federalism-oriented argument that states are uniquely suited to make.

B&S: How do the Brackeens have standing to challenge ICWA in the first place?

Lewerenz: You should ask them. The adoption at the heart of this case was resolved before it got to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Brackeens claim they still have standing because they are trying to adopt the younger sister of the boy they already adopted—they’re making a “capable of repetition” exception to mootness arguments. I don’t think this case really fits in that framework, because they’ve never amended their complaint to add that second adoption as an issue. Technically, that adoption falls outside of the claims in this case.

The other thing that the Brackeens have argued is that there is another set of plaintiffs in Minnesota who are presenting the same issue, and who are still trying to adopt the child they fostered. However, that case also got resolved in Minnesota state courts in 2021, and the plaintiffs did not appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the Brackeens never notified the Fifth Circuit. When you have multiple individual plaintiffs, a court can find that one plaintiff has standing and allow the whole case to go ahead. But if standing is based on the Minnesota case, there’s a real question as to whether the Brackeens have standing at all.

Carlisle Indian School c. 1903 (Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston/Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

B&S: That the justices are seriously considering the Brackeens’ Equal Protection argument feels like a product of how Equal Protection doctrine has evolved. It seems like the conservative justices are moving towards a jurisprudence where, as Roberts has already said, “The way to stop discriminating on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race”—as if everyone walks into the courtroom with the same blank slate.

Lewerenz: I think that’s where the plaintiffs want to go. That’s where the trial court judge wound up, and I think that there was a lot of sympathy for that argument on the Fifth Circuit as well.

We want to remain confident that the Court is not going to go there, because there is such a long history of express delegations of power concerning Indians. Even if we assume that Indian is indeed a racial category, the Constitution gave Congress the power to act on that particular racialized basis.

Erin Dougherty Lynch: The ICWA is still relevant today. There are states and jurisdictions where it has been inconsistently implemented, where there are disproportionate rates of Native children being removed from their homes, similar to what Congress saw when it was considering ICWA in the late 1970s. Alaska Native children are 20 percent of the state’s population of children, yet they are 60 percent of those involved in the child welfare system.

I would also point to both the Casey Family Programs brief, which talks about the benefits of ICWA not just for Native children, but for all children—how it’s considered best practice in child welfare proceedings.These are not just things that people are saying, like, “Oh, anecdotally, this is what I find to be the best.” These are research-based opinions.

Kinship care is the heart and the very center of ICWA. When you look at the briefs supporting the Brackeens, there is a telling lack of serious discussion about what results in the best outcomes for children. Our opponents are trying to tear down these protections for Native children, when anyone who is engaged in child welfare work agrees that the answer is to build up the child welfare system so that it better mirrors the provisions of ICWA.

Lewerenz: The medical and scientific communities are all on our side. If you’re looking for child welfare organizations, they’re all on our side. If you’re looking at Indian country, it is entirely on our side. If you’re looking at the states, 23 states joined the amicus brief on the pro-ICWA side. There’s a clear distinction in this case: On the pro-ICWA side, you have people who actually understand and study and care about children. On the other side, you have the attorney general of Texas, conservative think tanks, and people who make money marketing children.

I’m sure that the Brackeens love the child they have adopted, and love the child they are still trying to adopt. But they have chosen a path led by lawyers who are trying to burn down the whole system.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.