As Indian Law scholars and practitioners awaited the opinion in Castro-Huerta v. Oklahoma, the Supreme Court’s latest landmark case about Tribal sovereignty in the United States, the only real question was what Justice Amy Coney Barrett would do.

All the other justices’ positions were known: Justice Neil Gorsuch, a longtime Tribal sovereignty supporter who joined the liberals to form a five-justice majority in 2020’s McGirt v. Oklahoma, was likely to side with Castro-Huerta and the Cherokee Nation here. Chief Justice John Roberts dissented in McGirt, as did Justice Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh. Justice Clarence Thomas, in true Thomas fashion, largely agreed with Roberts and company, but wrote separately to argue that the Court lacked jurisdiction to review the case in the first place. So Barrett, the junior-most justice who replaced the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, would cast the deciding vote.

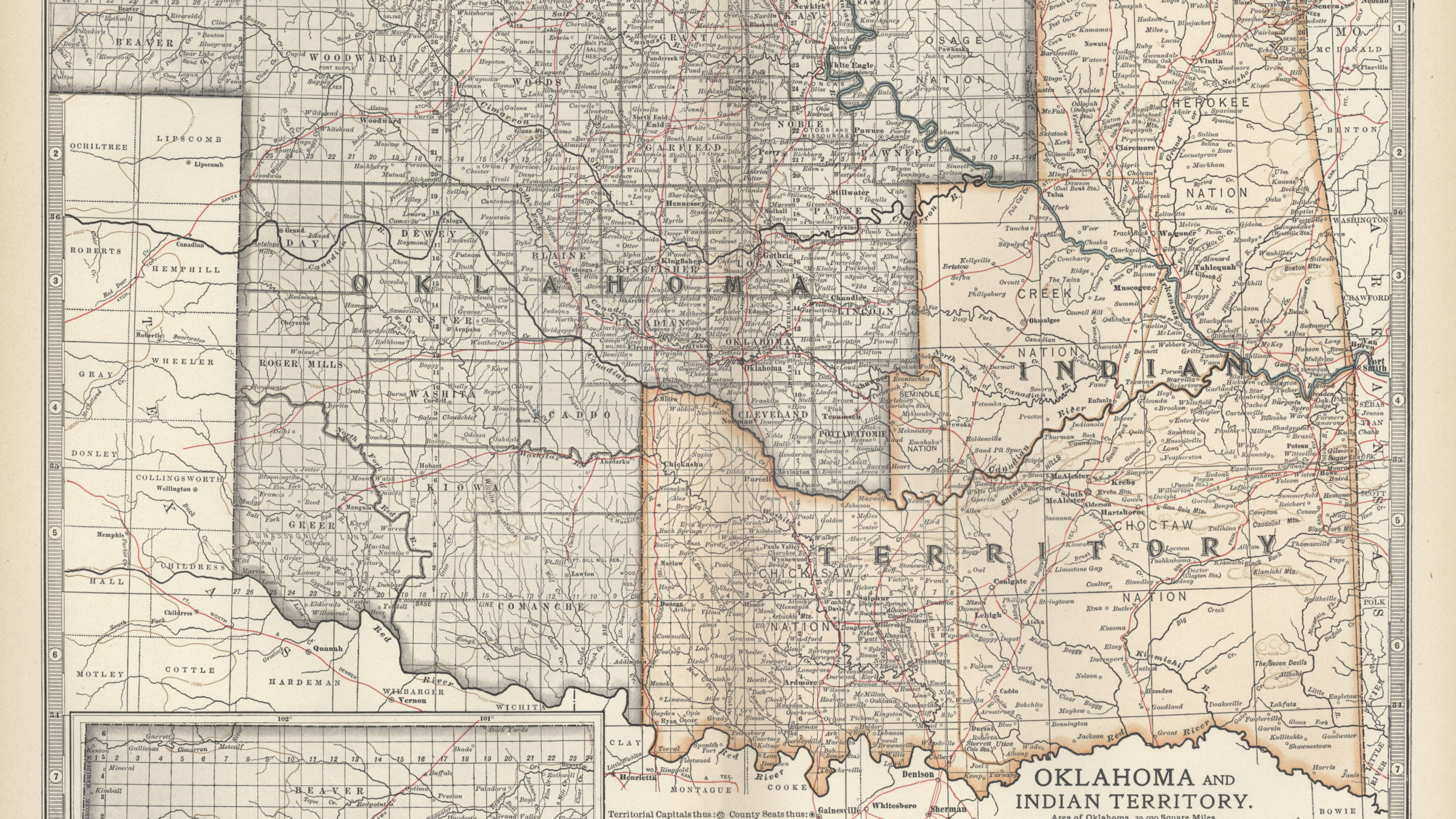

Castro-Huerta is about Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta’s appeal from a conviction for child neglect in Oklahoma state court. After McGirt, he appealed his conviction to the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals on the grounds that the state lacked jurisdiction, because the crime occurred in Indian Country and was committed by a non-Indian against an Indian. (In McGirt, the Court had held that for purposes of federal law, eastern Oklahoma is—and always has been—Indian Country, where states have limited power to prosecute.) The OCCA agreed and vacated Castro-Huerta’s state conviction. He was immediately charged in federal court, where he pleaded guilty to a charge of child neglect in Indian Country and consented to deportation by the Department of Homeland Security.

Governor Kevin Stitt and other carcerally-minded, anti-immigrant Republican politicians should have been satisfied with this outcome. Although his state conviction had been vacated, Castro-Huerta was set to be removed from the United States entirely. Yet, Stitt and his Attorney General John O’Connor were not satisfied and appealed the OCCA’s decision to the Supreme Court.

The intrigue over Barrett’s Tribal law jurisprudence peaked when she wrote the majority opinion in a different Tribal sovereignty case, Denezpi v. United States, in June. In Denezpi, Barrett invoked the dual-sovereignty doctrine to allow the federal government to prosecute a Navajo citizen who had been convicted in what are known as “CFR courts”—courts that enforce Tribal law and are administered by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. The majority held that the Double Jeopardy Clause did not apply to Denezpi because the laws under which charges were brought emanated from separate sovereigns. The outcome in Denezpi led some to believe that Barrett would follow the logic of McGirt and side with Gorsuch and the liberals in Castro-Huerta.

These hopes were dashed, however, when Barrett instead broke from Gorsuch to give the conservative bloc a decisive fifth vote, signaling a return to an era in which the Court subjugates Tribal sovereignty to state control. Kavanaugh, writing for the majority, explains that states and the federal government have concurrent jurisdiction over crimes committed by non-Indians against Indians in Indian Country, and that Worcester v. Georgia—the 1832 case that declared Indian Country to be separate from the states—was “abandoned” by the Court long ago.

Kavanaugh’s argument relies heavily on United States v. McBratney and Draper v. United States, two century-plus-old cases that extended state jurisdiction to crimes committed by non-Indians against non-Indians in Indian Country. Kavanaugh’s extension of these cases to a crime against Indians in Indian Country demonstrates a significant departure from traditional Indian law jurisdictional analysis. Although Castro-Huerta did not overrule McGirt, it enables states to further encroach on tribal sovereignty, and could allow the Court to hollow out Tribes’ post-McGirt gains by stripping them of civil and regulatory jurisdiction over Indian Country, too.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

The majority in Castro-Huerta twists itself into knots to create a solution in search of a problem. First, Kavanaugh demonstrates his deep misunderstanding of Indian law when he describes the case as “a crime committed in what is now recognized as Indian country (Tulsa) by a non-Indian (Castro-Huerta) against an Indian (his stepdaughter).” (The statute at issue uses the term “Indian Country,” as does every other relevant Indian law case; it is unclear why a textualist as diligent as Kavanaugh would pay so little attention to the language.) This ignores the opinion in McGirt, which explained that Oklahoma was wrong to have ever asserted jurisdiction over Indian Country. Instead of looking to where the crime occurred and to the tribal status of the victim and perpetrator, Kavanaugh focused on the nature and severity of the crime, Oklahoma’s putative reliance interests, and misleading statistics about criminal law in Oklahoma. He then attached all that to two factually inapplicable cases (McBratney and Draper) to reach his different, preferred conclusion.

Kavanaugh’s opinion also ignores the Indian Canons of Construction, which are supposed to help courts determine how statutes and treaties interact. The first canon states that treaty language must be construed how the Indians would have understood it at the time of its writing. (During the colonization of the Western United States, many Indians were not able to read and write English. Colonizers would take advantage of this by telling Tribal leaders one thing and then writing another in the treaty.) The second and third canons instruct courts to construe treaty language liberally in favor of Indians, and to resolve ambiguities in favor of the Tribe. These canons have formed the basis for nearly every Indian law case since their inception, but Kavanaugh mentions nary a word about them.

Had he considered the Indian Canons, his analysis would have come out much differently. The Treaty of New Echota, the treaty between the U.S. Government and the Cherokee Nation, is the founding document upon which any jurisdictional claim by the Tribe or the state of Oklahoma is based. In dissent, Gorsuch explains that New Echota, adopted in 1835—71 years before Oklahoma became a state—recognized that the Cherokee Nation “would enjoy the right to govern itself and remain forever free from ‘State sovereignties’ and ‘the jurisdiction of any State.’” Any honest analysis of New Echota would make clear that the Cherokee Nation and all parties to the treaty understood it to mean that the Tribe would be free of intrusions of state authority into its criminal jurisdiction. To suggest otherwise would be foolish and facially dishonest, which is perhaps why Kavanaugh decided not to mention it at all.

A map of Oklahoma and Indian Territory c. 1902 (Photo By Encyclopaedia Britannica/UIG Via Getty Images)

The outcome in Castro-Huerta signals that this Court does not understand how to protect Tribal sovereignty and/or does not care to learn to do so. As a result, it is likely to dismantle the Indian Child Welfare Act in Brackeen v. Bernhardt next term. Congress passed the ICWA in 1978 as a response to the tragedy of the “Termination Era,” during which the federal government attempted to “civilize” Indians by, among other things, forcibly taking Indian children from their families and relocating them to Westernized boarding schools. These facilities, known as “residential schools,” were often violent and dangerous. Congress passed the ICWA to prevent Indian children from being adopted out of Tribal communities unless absolutely necessary.

Brackeen involves the adoption of an Indian child to a white family against the wishes of the child’s Indian father. The adoptive family, backed on a pro bono basis by lawyers for some of the world’s largest oil companies, has challenged the ICWA on equal protection grounds, asserting that because the law gives adoption priority to members of a child’s Tribe, it uses an unconstitutional race-based classification. Under Morton v. Mancari, in which the Supreme Court held that Tribal citizenship is a political classification instead of a racial one, this argument is absurd. But this Court’s conservatives have already shown that they do not care about precedent so long as they have the votes to defeat it. With Barrett and Kavanaugh’s positions on Tribal sovereignty now clear, ICWA’s days may be numbered.

Castro-Huerta also throws cold water on the conservative conspiracy theory that Tribes can and will set up “on-demand abortion clinics” on Tribal land in the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. This was and is ridiculous; most Tribes have no interest in providing abortions outside of those allowed under federal law, which prevents Indian Health Service facilities from performing abortions except when necessary to save the life of the patient, or when the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest. Now, under Castro-Huerta, even a Tribe that wanted to provide abortion care to non-citizens is likely precluded from doing so, since any non-Indian practitioner could be charged and prosecuted under Oklahoma’s abortion ban. (Native Americans make up only 0.4% of the physician workforce in the United States, so finding a Native practitioner willing to provide abortions in Indian Country in the current political climate is exceedingly unlikely.)

Over the last decade, the Supreme Court had begun to lean towards protecting Tribes’ right to self-determination and self-governance. Castro-Huerta signals the end of that era, and the arrival of a Court primed to favor state interests over those of the Tribes. Expect to see more Indian law decisions that misapply the Court’s precedent in search of a preferred outcome, with Gorsuch and the liberals languishing in dissent for years to come.