The first bad doctor I encountered was a gynecologist who barged into the exam room without knocking, greeting me, or introducing himself. He fired off the obligatory questions, glancing up periodically, not so much to make eye contact as to glare in my general direction. When it was time to perform my pap smear, he inserted the speculum without warning and cranked it open, ignoring my winces. I told him the exam hurt; he said it was supposed to. He then jabbed my cervix with a swab, shoved the swab in a tube, and muttered something about when to expect the lab results as he degloved. He walked out the door the same way he’d entered it 10 minutes earlier—without a word.

As I left the office, my abdomen cramped intensely. Pap smears are never fun, but the discomfort usually ends when the exam ends. This visit wasn’t normal. The doctor seemed inexplicably scornful of me, and the exam bordered on violent. I felt violated.

My results came back normal, so a year later, when I received a reminder to schedule my next check-up, I kept putting it off—I was in no hurry to be poked and prodded like an animal again. Years later, when I finally brought myself to make an appointment, I learned that I had developed uterine abnormalities that could’ve been treated with medication if caught earlier. Now, I needed a surgery that cost me nearly $30,000 and left me bedridden for weeks. It was months before I could do basic things like carry my own groceries again.

This wasn’t the only time a bad doctor jeopardized my well-being. A general practitioner who spent under four minutes in the room with me failed to treat a topical allergic reaction; it became infected and inflamed, leaving me barely able to move my arms for a month. A gastroenterologist provided first-grade level anatomy lessons (“You know how people have six-packs?”) before blaming an asymmetrical nodule on a surgery that occurred after the nodule appeared. A dentist insisted that she’d sealed an onlay that I told her felt jagged and fragile; when it popped off a few months later, I had to foot the bill for a root canal.

Experiences like these have eroded my trust in the medical system. And although each offending doctor was different, they have one thing in common: None of them were Black.

Sometime this summer, the Supreme Court will decide two cases that could end affirmative action in colleges and universities. In the short term, this result would make elite institutions less accessible to people of color. But its impact would extend far beyond education policy: By changing the composition of medical school student bodies, it would entail devastating health consequences for Black people, who are less likely to seek preventive care and more likely to die from chronic conditions under the care of non-Black doctors.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Stories like mine are not uncommon among Black people. A 2017 study found that Black men live an average of 4.5 fewer years fewer than non-Hispanic white men, a difference that the authors attribute in large part to preventable chronic diseases. A 2018 study that randomly assigned Black men to a Black or non-Black doctor found that Black patients paired with Black doctors were 26 percent likelier to request a cholesterol screening and 20 percent likelier to request a diabetes screening—diseases that are potentially deadly, but also easily preventable.

The study’s authors attribute these results to Black doctors’ ability to establish better rapport with Black patients, who can then more readily recall and divulge details crucial to diagnosis and treatment. They conclude that Black patients under the care of Black doctors experience a 19 percent reduction in cardiovascular mortality. Other research shows that living in the same county as a Black doctor correlates with increased lifespans for Black people, regardless of whether that person is under the care of a Black doctor.

Medical schools have understood this for years. The Supreme Court’s first major affirmative action case, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, was about a policy at the UC Davis School of Medicine in the mid-1970s that “set aside” 16 seats in each class for qualified Asian, Hispanic, Black, and Native applicants. The other 84 seats were open to anyone.

One purpose of this program was to account for the history of racial discrimination against communities of color. But this was not the program’s only justification: As the Court put it in its eventual opinion, the program was also designed to improve the “delivery of health-care services to communities currently underserved.” In the case below, a California Supreme Court justice wrote that it was reasonable for Davis to attribute “the deplorable lack of effective medical services in minority communities” to a shortage of minority doctors—and to decide that an increase in the number of “disadvantaged minority doctors” might help.

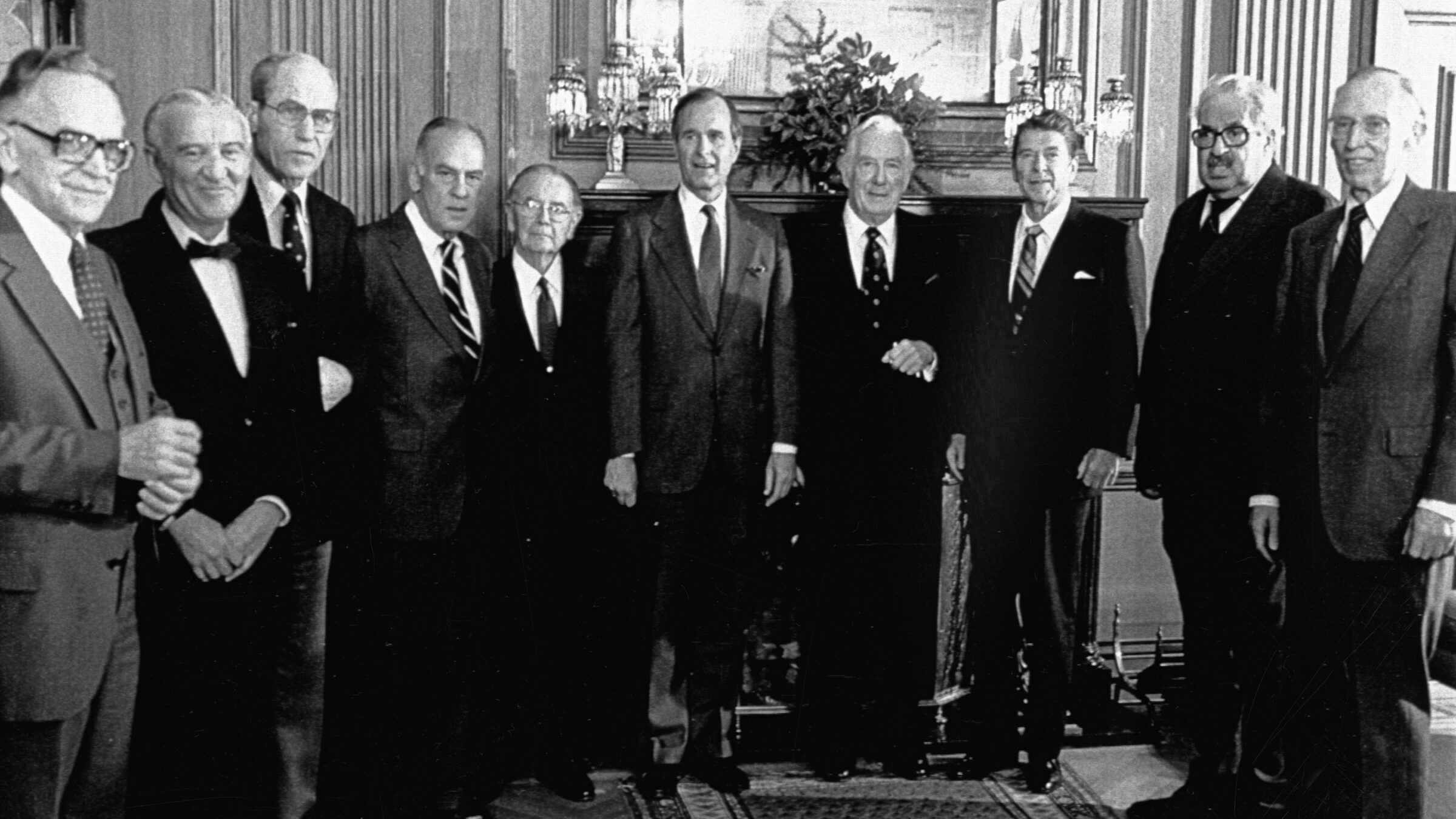

The Bakke Court with President-elect Ronald Reagan, November 1980 Bettmann / Contributor (Getty Images / Bettmann)

The Court’s opinion in Bakke split the difference: It decided that schools could consider the race of applicants when making admissions decisions, but could not impose numerical quotas. As for the school’s concerns about the provision of care to underserved communities, the Court agreed that this was an acceptable reason to consider race, but doubted that the special admissions program was “needed or geared to promote that goal.” (Writing for the Court, Justice Lewis Powell dismissed this rationale for the school’s policy as impractical, since it could not “assure that minority doctors who…expressed an ‘interest’ in practicing in a disadvantaged community” would actually do so.)

Much of the debate over Bakke and its progeny has centered on the legal question of whether the Fourteenth Amendment allows the government to take remedial action on behalf of victims of systemic racism. Lost in this debate is the ongoing real-world harm that non-diverse medical school cohorts have on Black patients. Although Black people comprise about 13.6 percent of the U.S. population, only 5.7 percent of doctors are Black. Many Black women, who are three times more likely to die following childbirth, literally cannot find Black obstetricians to provide the care they desperately need. The end of affirmative action would only make it more difficult for Black patients to find Black doctors going forward.

More Black doctors translates to Black people leading healthier, longer lives. By narrowing the permissible scope of race-conscious admissions practices in Bakke and subsequent cases, the Court has already diluted schools’ ability to address this reality. If the Court does away with affirmative action altogether, more Black people will suffer unnecessarily because of it.