It’s fair to say that very few people, myself included, saw what happened on Thursday coming. In a surprising 7-to-2 decision authored by Amy Coney Barrett, the Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. Haaland v. Brackeen, as this set of consolidated cases is known, had a lot riding on it for Indian Country. As Justice Barrett so succinctly put it, the legal issues in the years-long campaign against this landmark federal law were “complicated.” “But,” as she put it, “the bottom line is that we reject all of petitioners’ challenges to the statute, some on the merits and others for lack of standing.” In other words, this was as close to a blowout for tribal sovereignty as it gets.

One way to understand why the ruling in Haaland matters so much is to take it from Deb Haaland herself. A citizen of the Laguna Pueblo and the Biden administration’s interior secretary, she is the chief enforcer of the ICWA at the federal level, inheriting the litigation from the prior administration. “For nearly two centuries, federal policies promoted the forced removal of Indian children from their families and communities through boarding schools, foster care, and adoption,” she said in a statement in response to the ruling. “Those policies were a targeted attack on the existence of Tribes, and they inflicted trauma on children, families and communities that people continue to feel today.” As Haaland explains, Congress passed the ICWA more than 40 years ago to put an end to this history of abuse. “The Act ensured that the United States’ new policy would be to meet its legal and moral obligation to protect Indian children and families, and safeguard the future of Indian Tribes,” she added.

The challenge to the ICWA in Haaland was brought by three non-Indian adoptive families and a coalition of Republican-led states headed by Texas. Barrett doesn’t get into the gritty details of these adoptions, but we know that of the three families, only one was unsuccessful in adopting an Indian child, and that child was placed with her maternal grandmother who is a citizen of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe Tribe. Perhaps, as Barrett strongly implied in her opening, the who in this case is not so important in a case where all the legal claims lack merit. But the reality is that these families were merely a vehicle for a much more insidious group of monied interests operating behind the scenes that for years sought to destroy tribal sovereignty for their own personal and corporate gain.

The petitioners in Haaland mounted this multipronged challenge to the ICWA, throwing everything they could at it: They argued that Congress exceeded its authority under the Indian Commerce Clause and the Treaty Clause when it passed the ICWA; that the ICWA violates the Tenth Amendment’s anti-commandeering principle; and that the ICWA’s placement preference system, which gives primacy to Indian tribes, is a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. They brought all of these claims in front of the friendliest Republican-appointed federal judge they could find in Texas at the time, and that judge, Reed O’Connor, gave them everything they wanted.

The Supreme Court on Thursday put O’Connor in his place, making it clear that states have no authority when it comes to tribal relations. The Court has held nearly without fail over the last 200 years that Congress has practically absolute authority to legislate in Indian Country. This authority includes power to legislate over the Tribes and the individuals who make up the Tribes. The petitioners had argued that the ICWA exceeds Congress’ authority under the Indian Commerce Clause because “children are not commerce”—a bold position to take considering that the private adoption industry has surfaced as one of the leading groups attempting to overturn the ICWA. But as Barrett notes, such an argument flies in the face of the Court’s lengthy jurisprudence on Indian law. A state’s interest in the adoption of an Indian child simply does not displace Congress’ authority over tribal relations.

More importantly, Barrett’s opinion denied standing—or the right to sue—to every single plaintiff in these cases on their claims that the ICWA violates the Equal Protection Clause. TheICWA permits the child’s Tribe to intervene in adoption proceeding and invoke placement preferences, where non-Indian families are effectively put at the bottom of the list. Under these preferences, the Tribe can require that the child be placed with any individual Indian or Indian institution, regardless of tribal affiliation. The petitioners argued that this scheme racially discriminates against non-Indians in adoption proceedings involving Indian children. Barrett denied these claims without considering their merits because none of the individual petitioners had shown that they were actually harmed by the ICWA’s supposed racial preference system. (I say “supposed” because there’s nothing racial about giving Tribes preferential treatment in adoption proceedings; as Justice Neil Gorsuch put it in concurrence, “Indian Tribes remain independent sovereigns with the exclusive power to manage their own internal matters. As a corollary of that sovereignty, States have virtually no role to play when it comes to Indian affairs.”) Texas, for its part, also challenged the ICWA on equal protection grounds under a loosely crafted parens patriae argument on behalf of its citizens; the state had claimed that enforcing the ICWA would require the state to “break its promise to its citizens that it will be colorblind in child-custody proceedings.” Barrett again rejected this argument because it fails to demonstrate a real-life injury to the state’s interests.

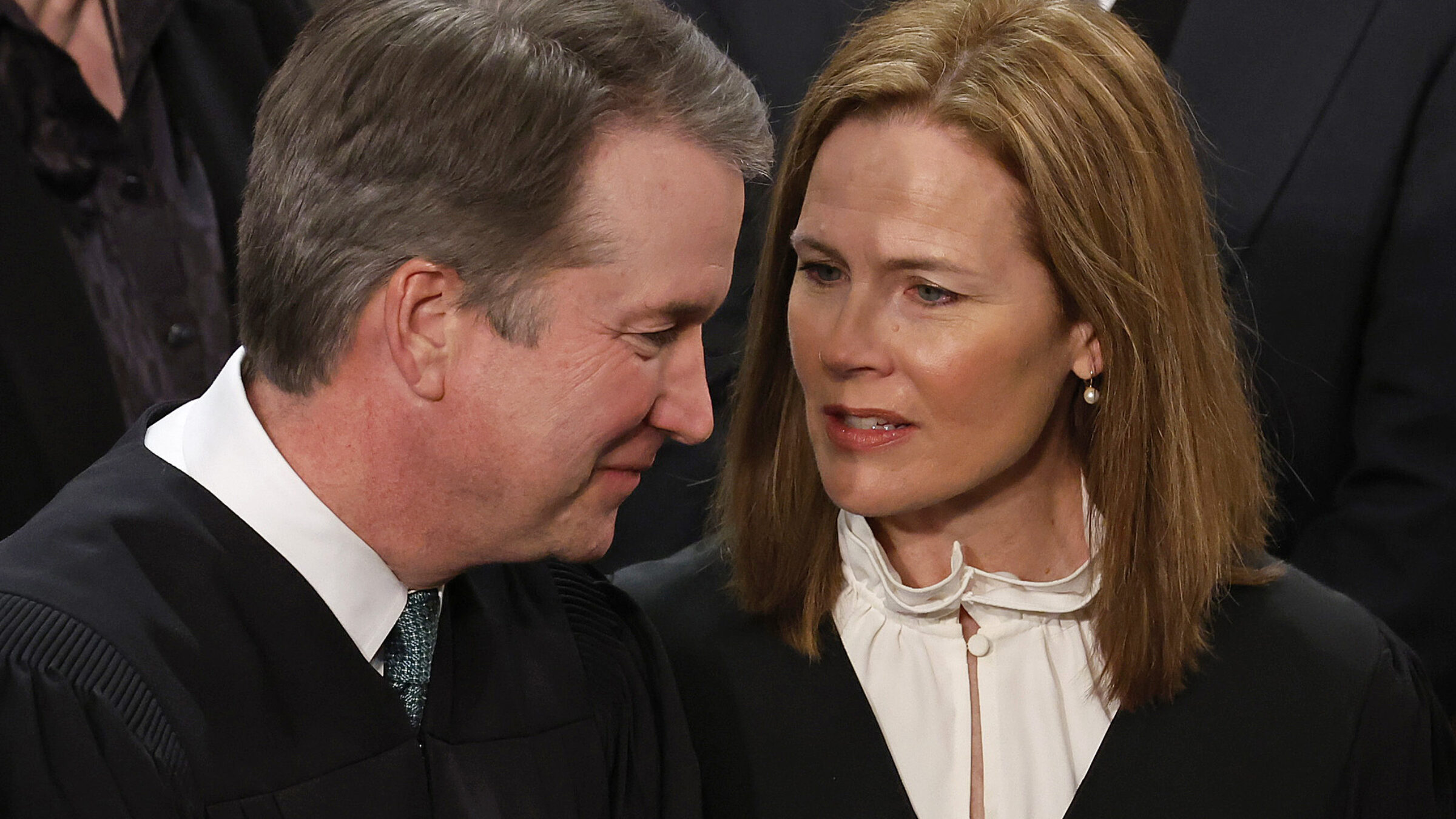

The equal protection victory may prove to be short-lived, however, as Justice Brett Kavanaugh offered a two-paragraph concurrence where he left the door open to a challenge based on the ICWA’s tribal preferences scheme. For all his brevity, Kavanaugh once again demonstrated his total ignorance about Indian law. Decades ago, the Court ruled in Morton v. Mancari that tribal citizenship is a political, not a racial, classification. The Court has held firm on this issue, so it is disappointing yet clarifying to see that Kavanaugh—and arguably Barrett, who doesn’t attempt to rebut him—appears to have neglected such a basic principle of Indian law.

Even with that potential mischief looming, it appears that Gorsuch, a known supporter of tribal sovereignty, has made some headway with his fellow Trump justices on the Court with respect to Indian law. Last year, he dissented furiously from Kavanaugh’s opinion in Castro-Huerta v. Oklahoma, joined by Barrett, that all but stripped Tribal Nations of civil and regulatory authority over their own affairs, leaving them at the mercy of state encroachment. In light of that ruling, which was widely condemned in Indian Country, Haaland is a pleasant reprieve from where things appeared to be headed just a year ago. (Gorsuch, for good measure, dissented alone and offered an impassioned defense of tribal sovereignty in a separate case decided Thursday where the Supreme Court held that the federal bankruptcy code displaced the sovereign immunity of Indian tribes.)

Other than the fierce political blowback from the end of Roe v. Wade last summer and the arrival of Ketanji Brown Jackson, it’s unclear what’s changed at the Supreme Court since Castro-Huerta. When the Court took up this case in February of last year, months before all this turmoil and the justices’ cratering approval ratings, many—including yours truly—believed that the end was near not only for the ICWA, but for tribal sovereignty itself. But those who have stood up for the ICWA were able to breathe a sigh of relief on Thursday. The ICWA has been the battleground over tribal sovereignty for the last decade; the private adoption and oil and gas industries have worked tirelessly to destroy tribal sovereignty in the name of commodifying our people and our land. But at least for now, Native peoples’ ability to maintain their traditions will live on.