The conservative wing of the Supreme Court got to spend three-plus hours yesterday waxing philosophical about one of its favorite topics: giving itself more power. On Wednesday, the justices heard oral argument in Relentless v. Department of Commerce and Loper Bright v. Raimondo, two highly-anticipated cases about federal regulations that require commercial fishing companies to help pay for third-party monitors of fishing practices on their boats.

That might not seem like much on the surface, I know—Justice Neil Gorsuch described the subject matter as “prosaic.” But dig a little deeper (er, swim a little deeper?) and it becomes clear that conservative interest groups manufactured these cases in order to dismantle the administrative state. And at oral argument, the Republican appointees signaled that they’ll accomplish this task by undermining how government works altogether.

Both cases ask the Court to overturn Chevron v. NRDC, a landmark Supreme Court case that has facilitated the work of federal agencies for forty years. When Congress tasks a federal agency with enforcing an ambiguous federal law, Chevron requires courts to assess the agency’s exercise of its own discretion for reasonableness. If the agency is acting reasonably, the court stays out of the agency’s way. This concept, known as Chevron deference, basically lets agencies do the jobs they’re tasked with doing so long as they use their brains as they do so. The legislature establishes a lane, the executive does its thing in that lane, and the judiciary merely makes sure the executive stays within it.

Without Chevron, that policymaking authority—the doing of things in the lane—shifts away from the elected branches of government to unelected, unaccountable courts. This is a thrilling possibility for conservative activists both on and off the bench—who, as Mark Joseph Stern notes at Slate, were pretty much fine with Chevron until courts started using it to uphold regulations promulgated under Democratic presidents. The workings of hundreds of agencies regulating everything from agriculture to hazardous materials would no longer be determined by experts, but instead by the likes of Justices Sam Alito, Clarence Thomas, and active texters in the Federalist Society groupchat.

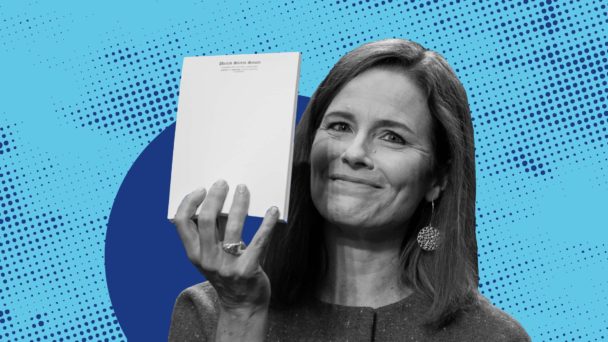

Trying to explain to someone at happy hour just how small you want the government to be (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

It’s hard to overstate how disruptive this would be; as Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar told the Court, overruling Chevron would create an “unwarranted shock to the legal system” and “introduce instability” across many areas of law. The liberal justices repeatedly asked the lawyers whether agencies or courts are better positioned to decide agency policy; Justice Elena Kagan invoked real examples of agency deliberations to highlight how ill-equipped courts would be for the job. “Does the term ‘power production capacity’ refer to AC power that is sent out to the electric grid, or DC power that’s produced by a solar panel?” she asked Roman Martinez, counsel for one of the fishing companies. “Is a new product designed to promote healthy cholesterol levels a ‘dietary supplement’ or a ‘drug’?” As Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pointed out, these hypotheticals are difficult “because, at bottom, they’re not asking legal questions; they’re asking policy questions.”

When implementing broad or ambiguous statutes, hard decisions like these are inevitable. The key question, Justice Sonia Sotomayor emphasized, is “who makes the choice or helps you make the choice” between reasonable policy options. Chevron answers that question by telling judges to defer to the agency. Absent Chevron, each judge could answer as they, personally, see fit—which can, as Kagan observed, yield answers that are “awfully ideological in nature, awfully partisan in nature.”

The conservative justices seemed far less troubled by the implications of such a result. Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote the opinion overturning Roe v. Wade less than two years ago, asked Martinez to explain why the liberals’ fears that judges would end up “allowing their policy views, consciously or unconsciously, to influence their interpretation of the statutes” are “unfounded,” which is about as loaded as a loaded question can get. (Martinez’s response: congratulating the Court for moving away from “free-form analysis” and adopting a “text-focused” approach.) Alito, Gorsuch, and the lawyers for the fisheries, both of whom are conservative legal movement stars with lovely bios on the Federalist Society website, seemed to coalesce around the answer that there’s nothing to worry about with them in charge. Judges make the right decisions now; it just so happens that those judges are all on the right, too.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh kind of gave the game away when he criticized Chevron for allowing agencies to change their minds, as he put it, “every four or eight years when a new administration comes in.” This is literally how elections are supposed to work: The executive branch is supposed to respond to the will of the voters by governing differently than the previous one. Kavanaugh and company are effectively advocating for Republican-captured courts to have the authority to lock in federal policy in perpetuity.

With Relentless and Loper Bright, the conservative legal movement is poised to wreak havoc throughout the federal government and curb its ability to actually serve the public. The Court’s conservatives have proven that they will continue arrogating power from the other branches until the other branches make them stop.