Zackey Rahimi, a 23-year-old Texas man involved in at least six shootings between November 2020 and January 2021, would be the first to tell you that Zackey Rahimi should not have access to a gun. In April 2021, he was charged with and later convicted of possessing a firearm while under a domestic violence restraining order—a federal crime. And about a year ago, in a handwritten letter to the judge and prosecutor in his case, Rahimi promised to “make sure for sure this time” to “stay away from all firearms & weapons.”

At the same time, Rahimi was mounting a constitutional challenge to the federal statute that formed the basis of his conviction, arguing that the government cannot legally make that choice for him. Today, the Supreme Court disagreed, ruling 8-1 in United States v. Rahimi that a federal law prohibiting people subject to domestic violence orders from possessing guns does not violate the Second Amendment. Justice Clarence Thomas was the lone dissenter.

This case was the first big test for the rule the Court established two summers ago in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, in which Thomas, writing for the six-justice conservative supermajority, declared that laws regulating guns are presumptively unconstitutional unless they are “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” Because of Bruen, the legality of virtually every gun regulation was suddenly called into question, and overworked and understaffed lower courts embarked on frantic historical safaris to find Founding-era matches to today’s gun laws.

In Rahimi, the Court backed away somewhat from Bruen’s sweeping changes to constitutional law, emphasizing that a modern regulation need not have a historical twin; perhaps it can have a historical sibling or cousin. “Some courts have misunderstood the methodology of our recent Second Amendment cases,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority. He blamed the chaos on lower courts’ interpretation of Bruen rather than Bruen itself, which, he said, was “not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber.” Rahimi shows that a majority of the Supreme Court realized that it could apply Bruen as written, or it could not embarrass itself by having to stand by Bruen’s batshit consequences, but it could not do both.

In Rahimi, Roberts explained that a law disarming people subject to protective orders “fits comfortably,” actually, within a longstanding historical tradition: “Since the founding, our Nation’s firearm laws have included provisions preventing individuals who threaten physical harm to others from misusing firearms,” he wrote. The opinion discussed Founding-era surety laws, which required potentially violent people to post bonds guaranteeing their good behavior, and affray laws, which barred people from fighting in public, and essentially concluded that they were close enough to the law at issue here. Not an exact match, but not a mismatch either.

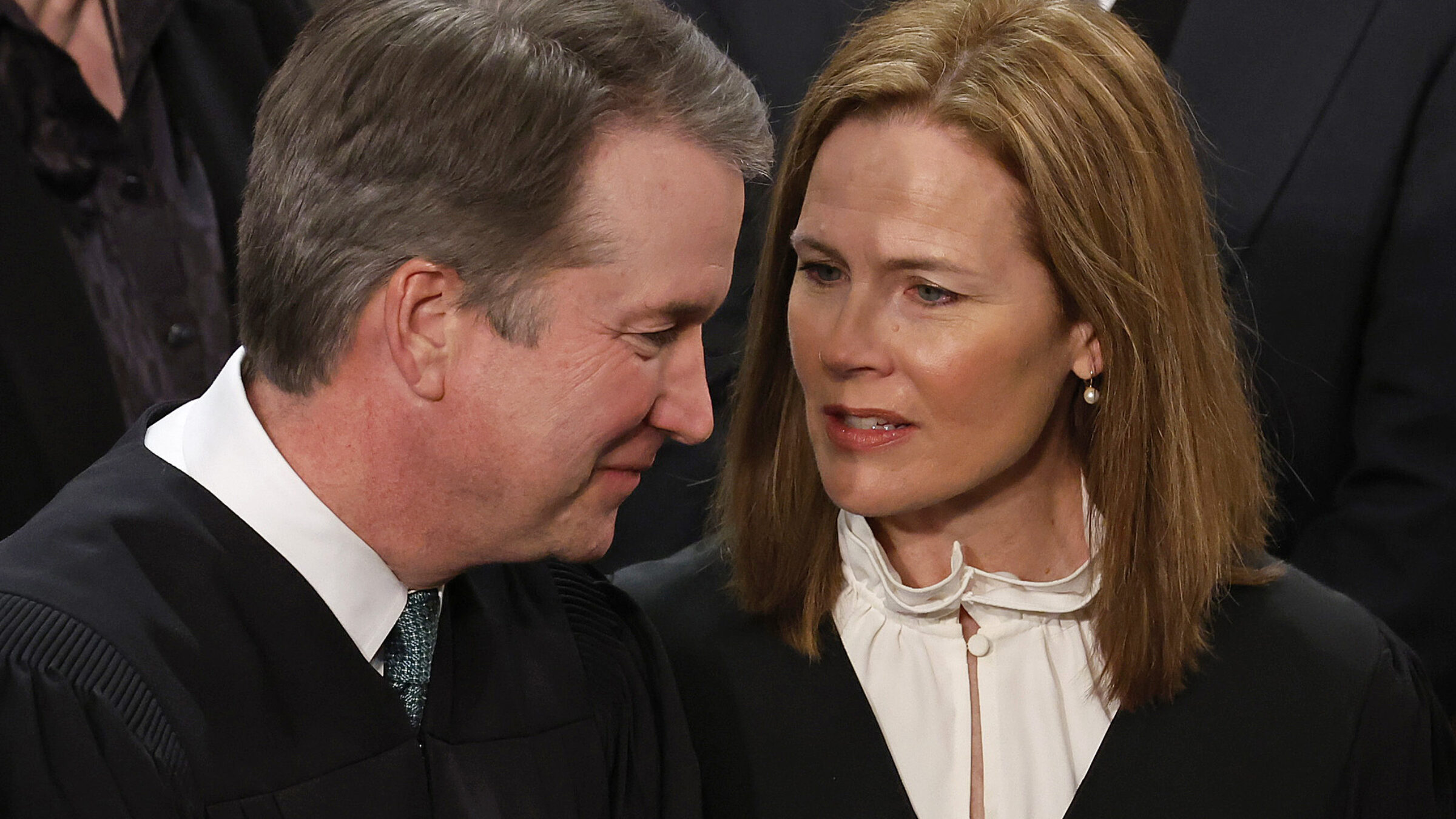

Multiple conservative justices authored concurring opinions trying to simultaneously clean up the Court’s history-and-tradition-fueled mess, and deny that they made a mess to begin with. They insisted that originalism is still the correct method of constitutional interpretation, and that despite their deviation from Bruen’s full-throated embrace of originalism, they are still good originalists. Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that although it “may sometimes be difficult” to discern “what the original meaning of the Constitution requires,” that question “is the only proper question a court may ask.” Likewise, Justice Brett Kavanaugh insisted that history is the “proper guide” for judges, since judges who don’t stick to history will stick to their individual policy preferences instead. (Apparently, the only two options for constitutional interpretation are YOLO and WWJD, where the J stands for Jefferson.)

Justice Amy Coney Barrett declared that “original history” is “generally dispositive,” but acknowledged that at least some subjectivity is inherent in this process—judges who look towards history must still decide what history it is they’re looking for, after all. That said, she concluded that the Court got the analysis right here; these “harder level-of-generality problems,” Barrett concluded, “can await another day.”

When you fucked up, and have some intellectual backfilling to do (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Justice Sonia Sotomayor authored a concurrence, joined by Justice Elena Kagan, that highlights the trap of originalism’s obsession with history: It allows conservative justices to cherry-pick facts that yield conservative results. History can play a role in constitutional interpretation, sure, “but a rigid adherence to history, particularly history predating the inclusion of women and people of color as full members of the polity, impoverishes constitutional interpretation and hamstrings our democracy,” she wrote. Sotomayor and Kagan, and, in a separate concurrence, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, all agree that Bruen was wrongly decided, and that neither courts nor lawmakers should be bound by selective history at the expense of all other considerations. In light of lower courts’ struggles to apply Bruen, Jackson urged the Court to “be mindful of how its legal standards are actually playing out in real life.”

The real lives of real people alive today are absent from Thomas’s analysis. In dissent, he remains adamant that history is the determinative factor of a gun law’s constitutionality, and that the “central considerations” when comparing modern and historical regulations are whether they “impose a comparable burden” that is “comparably justified.” In his mind, the only question is whether there were similar laws at the Founding, and whether those laws served similar purposes. Thomas asks if nonconvicted domestic violence offenders were ever categorically disarmed, answers that they were not, and concludes they cannot be now or ever.

In Rahimi, Thomas is ride-or-die for the standard he created in Bruen. But no other justice is comfortable with the rule or its consequences. The liberal justices are upfront that the Court got the Constitution wrong, and the conservative justices—both those in the majority and those writing separate, flailing concurrences—pick laws with varying degrees of generality out of a historical grab-bag to support the conclusion they want to reach. All Republicans except for Thomas were forced to confront the reality that, if the rule in Bruen prevents the government from disarming domestic abusers, perhaps they’re not as committed to the rule in Bruen as they thought. As it turns out, the conservative justices prioritize fealty to history and tradition over everything—until this approach leads to policy outcomes they don’t like.

Bruen, which prevented legislators from addressing the modern gun violence crisis unless they could convince the Court that long-dead lawmakers had a sufficiently similar idea about muskets, was always absurd. Rahimi exposes that Bruen was built on a lie: It demanded that judges rely only on a certain history, and that they ignore any other bits of evidence, context, or history that they find inconvenient. At oral argument, Justice Elena Kagan accused Rahimi’s attorney of “running away from your argument because the implications of your argument are just so untenable.” Today, the Court essentially did the same thing.