In November 2020, Zackey Rahimi messaged a young woman on Snapchat that he “had something for her.” The woman agreed to meet Rahimi in a parking lot, but discovered that the thing he had was a gun. As she got back into her car and drove off, Rahimi shot the car “multiple times,” per a police report.

What makes this story national news rather than crime blotter fodder is that this guy, of all people, will soon appear before the Supreme Court and argue that the U.S. Constitution entitles him to carry a gun. In United States v. Rahimi, which is set for oral argument in November, the Court will decide whether the government can legally take guns from people it knows are threats to their partners and lower the odds they make good on those threats, or if the government will let abusers keep their guns and let the cards (women’s bodies) fall where they may.

Zackey Rahimi is not what one might call a “responsible gun owner.” He shot his AR-15 rifle into the house of a guy he sold drugs to for “talking trash” about him online. He shot at a guy he got into a car accident with, left the scene of the accident, and then returned to shoot at the guy again. He shot into the air in a residential neighborhood in front of kids. He shot at another car on the highway when a truck flashed its headlights at him. He shot into the air at a Whataburger when his friend’s credit card was declined. All five of these shootings took place between December 2020 and January 2021; they are also just the ones police know about.

Earlier this week, HuffPost reported on police reports that reveal that Rahimi’s winter shooting spree actually began even earlier, in November 2020. The briefing in Rahimi does mention that Rahimi had “threatened another woman with a gun” in that month, but elides the facts that, per HuffPost’s reporting, he lured the woman to a parking lot, waited for her wearing all black and a ski mask, and repeatedly fired his gun at her as she drove away.

Gun reform advocates and anti-domestic violence organizations have argued for years that private violence is a bellwether for public violence. Rahimi makes their point for them: In December 2019, he shot at a bystander who saw him pushing and shoving his then-girlfriend into a car where she hit her head on the dashboard. He later called his ex and threatened to shoot her, too, if she told anyone what happened. In February 2020, a Texas state court entered a restraining order to protect Rahimi’s ex-girlfriend and child after the court found that his violence was “likely to occur again in the future.”

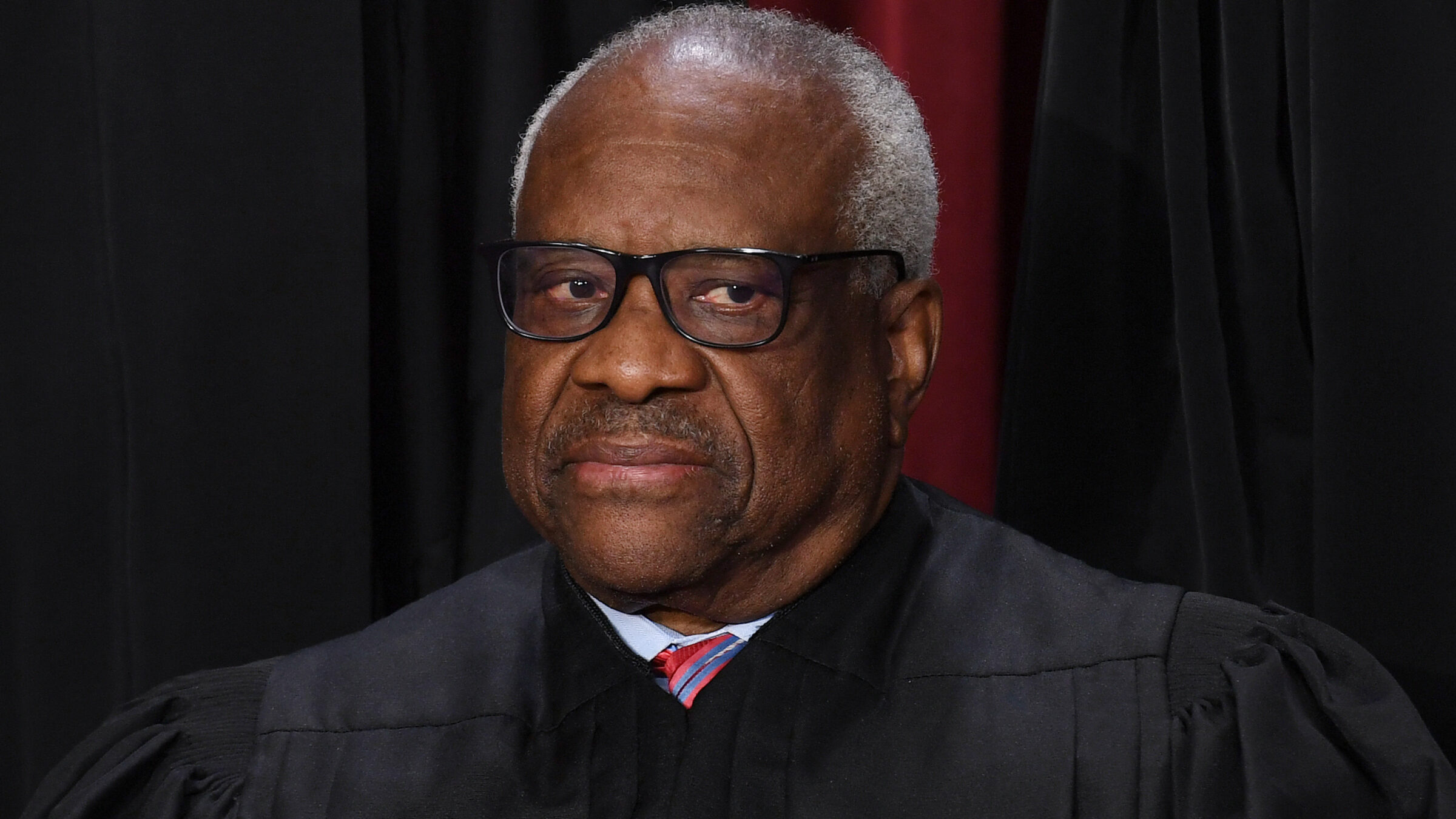

When someone suggests the government do something about gun violence (Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP via Getty Images)

Rahimi pleaded guilty in 2021 to unlawfully possessing a gun while subject to a restraining order. But after the Supreme Court handed down its decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen in 2022, ruling that any modern gun regulation must have a “well-established and representative historical analogue,” Rahimi realized he might still have a shot (sorry). He persuaded a federal appeals court that it must now follow the standard set out in Bruen by Justice Clarence Thomas, which means that a federal law blocking domestic abusers from possessing guns violates his Second Amendment rights.

“The Government cannot say that the founding generation was unaware of domestic violence as a social problem,” Rahimi’s attorneys wrote in a brief to the Supreme Court. “The Founders could have adopted a complete ban on firearms to combat intimate-partner violence. They didn’t.”

Rahimi will be the Supreme Court’s first gun case since it leaned all the way into originalism’s “being better than your forebears is illegal, actually” standard in Bruen. That standard may prove helpful to men who hurt women and never met a problem a gun couldn’t fix. Already, an American woman is shot and killed by her partner every 16 hours. Men who abuse women are five times more likely to kill their partner when they have access to a gun. An expansion of the Second Amendment in Rahimi will put more women in more danger of getting hurt or killed. The Supreme Court will be responsible for it.