Last week, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Shinn v. Ramirez, a case about whether federal judges can consider evidence of bad lawyering by state-appointed lawyers before states are allowed to execute those lawyers’ clients. David Ramirez and Barry Jones, two men on Arizona’s death row, want to argue that their state-appointed attorneys represented them so badly that they are entitled to new trials, at the very least.

But Arizona, ever the vanguard in executing people with as little due process as possible, argues that federal law bars the men from doing so—regardless of their potential innocence.

Jones was convicted of murder in 1995. But he has always maintained his innocence, and says his state-appointed trial lawyers did a terrible job of investigating, well, anything that might turn up evidence of his innocence: For example, they did not investigate alternative suspects, or call expert witnesses to rebut some of the state’s more dubious theories that relied heavily on junk science and shoddy police work. Similarly, Ramirez’s state-appointed lawyers didn’t present mitigating evidence of his intellectual disability and severe childhood trauma. His was their first-ever defense of a death penalty case.

Usually, people like Ramirez and Jones can contest their sentences in federal court through the law of habeas corpus, which allows people to challenge whether their punishments are constitutional. In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled in Martinez v. Ryan that people sentenced in state courts due in part to ineffective lawyering can later present their claims in federal habeas courts, even if state law tries to limit that right. In 2018, a federal judge sided with Jones under Martinez and ordered his release, noting that the failures of his lawyers “pervaded the entire evidentiary picture presented at trial.” Ramirez earned a hearing, too, in light of what the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals called the “substantial” evidence of his trial lawyer’s incompetence.

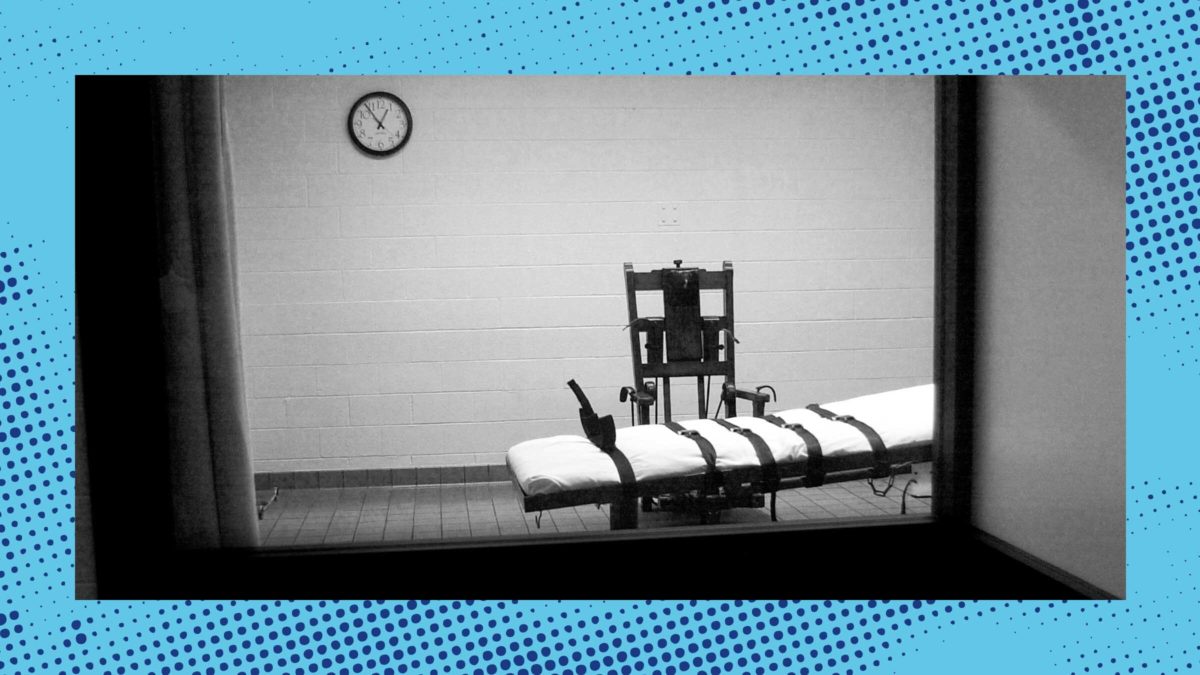

Here’s where things get complicated, though. In 1996, Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, a key provision of which bars people sentenced in state court from presenting new evidence in federal habeas proceedings—no matter how exculpatory—if the defendant didn’t “develop” that evidence in state court first. The Congress that passed AEDPA found a willing partner in Arizona, which has long distinguished itself in its appetite for putting people to death. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, of the 186 death row exonerees since 1976, ten were sentenced in Arizona. In the three decades since Jones and Ramirez were sentenced, Arizona has executed over three dozen people. Earlier this year, the state refurbished its gas chamber.

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images

Prosecutors could have responded to the courts’ findings in Jones’s and Ramirez’s cases by retrying the two men. Instead, Arizona is pushing the Court to render its decision in Martinez meaningless, asking for permission to kill both men without further delay, like a two-for-one execution deal. Under Martinez, Arizona argues, federal judges might be allowed to hear claims of inadequate representation, but under AEDPA, they can’t consider any new supporting evidence for these claims. This result would create an obvious Catch-22 for defendants: It is really, really hard to have “developed” evidence in state court if the whole problem is that your lawyer didn’t bother to find it.

The justices, in a decision likely to be issued next year, will have the final say in Shinn on how to reconcile AEDPA and Martinez. The draconian structure of Arizona’s criminal legal system, which allows defendants to raise ineffective lawyering claims only during post-conviction review, introduces another wrinkle to this question: Without the protections of Martinez, a defendant with evidence that both their trial and post-conviction attorneys botched his case would have no forum in which to present it. As Innocence Project executive director Christina Swarns put it in a New York Times op-ed, Jones “lost the lawyer lottery twice.”

If you’re wondering why Arizona wants the Court to rule against defendants this time when it seemingly came down the other way less than a decade ago, you’re not alone. “To what end,” asked Justice Clarence Thomas during oral argument, would the Court have decided Martinez as it did if defendants couldn’t present new evidence of inadequate representation? Making arguments about past bad lawyering, after all, almost always requires an investigation to uncover new facts that the allegedly bad lawyer should have found out.

Incredibly, the state Solicitor General admitted that for someone like Ramirez or Jones, trying to make the case based on the state court record alone would be a “fruitless exercise,” but that the text of AEDPA leaves no other option. In Arizona’s warped view, only a person whose lawyers botch a death penalty trial while having the presence of mind to document helpful evidence of their own bad lawyering has any hope of success. Otherwise, not even the defendant’s innocence, the state argued, would be enough to warrant review.

The justices seemed skeptical of Arizona’s position at oral argument. But the mere fact that the state has adopted this stance as part of its crusade to kill Jones and Ramirez should scare anyone who believes “innocent until proven guilty” means anything anymore. Ensuring the availability of procedural mechanisms that allow as much review as necessary is the bare minimum for a system that allegedly abhors the punishment of innocent people. An appeal of a death sentence is never a frivolous request.