On Monday, the Supreme Court published its opinion in Federal Election Commission v. Ted Cruz for Senate, a challenge to a 20-year-old anti-bribery law brought by a Republican lawmaker who is likely to mount a very expensive bid for higher office in the not-so-distant future. Before a six-justice conservative supermajority that believes the First Amendment functions as a near-absolute bar to meaningful campaign finance regulation in America, I will give you one guess as to how this case turned out.

The rule at issue in Ted Cruz for Senate is simple. If you, a candidate for office, lend your own money to your campaign, federal law allows you to use money you raise before the election to pay back those loans, since those donations fund a bid for office that may or may not pan out. But for donations you receive after voters decide the election—donations that, by reducing your debt, functionally go into your pocket—the rules are a little different: You can use these donations to pay yourself back only up to $250,000. Anything beyond that, and you’re out of luck.

This case made it before the Supreme Court thanks to—you guessed it—Texas Senator Ted Cruz, who structured the financing of his 2018 Senate campaign for the specific purpose of picking the fight he won this week. The day before the election, Cruz loaned his campaign $260,000, which astute readers will note is $10,000 above the statutory limit. After time ran out to pay off the difference using donations he received before the election, he sued for the right to use donations he received afterwards instead.

The rationale for this quarter-million-dollar threshold is obvious to anyone whose preferred political party does not depend heavily on the largesse of ancient reactionary kajillionaires: Post-election donations provide a convenient mechanism for donors seeking to buy access, favors, or votes, or otherwise ingratiate themselves with an officeholder-to-be. As the government put it in a brief, donations to victorious candidates are different because they are no longer bets; they are bets on a sure thing.

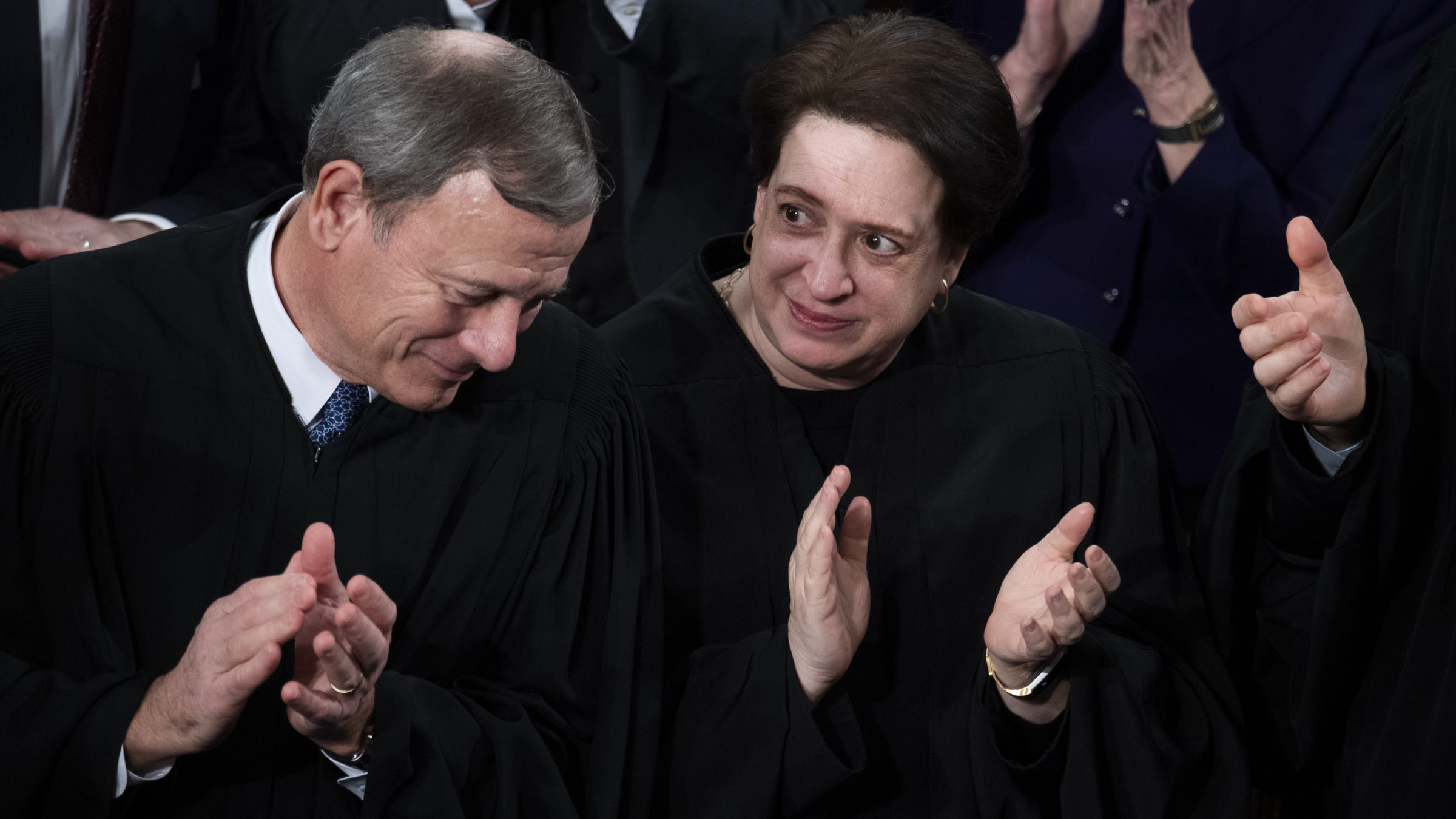

When your Supreme Court favs put a lil money in your pocket (Photo by Samuel Corum/Getty Images)

Chief Justice John Roberts, who wrote for the six conservatives in Ted Cruz for Senate, sees no problem with this arrangement—which, he says, preserves the “influence and access” that “embody a central feature of democracy.” In a key passage, Roberts explains that post-election donations used to repay candidate loans are not “gifts” of an ethically troubling nature, since they merely restore the candidate to their financial position before they volunteered to write their campaign a six-figure check. “If the candidate did not have the money to buy a car before he made a loan to his campaign, repayment of the loan would not change that in any way,” Roberts writes.

This purported distinction is as dumb as it is morally bankrupt, because you do not need to be a fancy lawyer to understand that this is simply not how money works. Imagine I, a fourth-grader, spend months saving my allowance to buy an iPod. But at the last minute, I decide to take my iPod fund and spent that money on an Xbox instead. Although I enjoy my newfound gamer lifestyle, I realize how much more fun I would be having if I could listen to hours of skip-free music at the same time. I thus ask my parents to cover my iPod-related expenses; since I had the money in the past, I explain, it is only fair for them to reimburse it.

My parents, of course, would have laughed in my face. But if for some reason they did decide to replenish my voluntarily-depleted savings, I would have received money I did not have, that I could then use however I please. Anyone who has attended a birthday party before recognizes this as what it is: a gift. The fact that I had more money before I spent it on something else makes me like every single person who has ever purchased anything. The difference between this scenario and the law Roberts and company struck down is that one is a dumb hypothetical about my childhood spending priorities, and the other involves the honest-to-God Supreme Court deciding that maybe facilitating legal bribes is its solemn responsibility.

Justice Elena Kagan, joined in an incredulous dissent by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer, sounds like an exasperated teacher ready to send Roberts to the principal’s office because she can no longer tell if he’s being purposefully obtuse as a bit. “However much money the candidate had before he makes a loan to his campaign, he has less after it,” she writes. “So whatever he could buy with, say, $250,000—surely a car, but that’s beside the point—he cannot buy any longer.”

When your boss is being a real weirdo (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

The more basic problem here is that Kagan probably lost this case the moment the Court decided to hear it. Conservatives have long pushed for expansive readings of the First Amendment that bless political spending as protected speech, quietly greasing the electoral skids for candidates who share their policy agenda. Under Roberts’s leadership, the Court has so tightly constrained the grounds for permissible government restrictions on political spending-as-speech that basically none remain: A legislature’s or electorate’s desire to limit money in politics, for example, is insufficient; so, too, are desires to level the playing field among candidates, or to curtail the influence of donors over elected officials.

Previously, the Court had left open the possibility that laws designed to combat quid pro quo corruption—smoking-gun exchanges of money for favors—might pass constitutional muster. But as Ted Cruz for Senate makes clear, Roberts and company are no longer pretending to care about cartoon-villain wrongdoing like this. As Kagan pointedly notes, the potential for quid pro quo corruption here is “self-evident” to everyone except, apparently, to six of America’s fanciest lawyers who are not accountable to anyone.

Roberts goes on to assert that no well-documented evidence of quid pro quo corruption exists that would justify the law’s continued enforcement. This claim is, at best, dubious. In dissent, Kagan notes several elections that were not subject to this rule in which savvy post-election donations—surprise!—paid off handsomely for people who invested in their new elected official’s future decisionmaking processes.

Setting aside that factual dispute, though, Roberts’s analysis has the Court’s role backwards. A functioning legal system would protect the public’s interest in the integrity of the democratic process. Roberts’s position is that there is no need for laws that prevent illegal corruption without proof that illegal corruption has already compromised the democratic process. This basic absence-of-evidence-as-evidence-of-absence mistake echoes Robert’s 2013 assertion in Shelby County v. Holder that legal protections for Black voters in states in the Jim Crow South were not necessary because more Black people than ever were voting in states in the Jim Crow South. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s retort—that gutting federal laws that block state-level voter suppression efforts “is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet”—is as apt today as it was nearly a decade ago.

The upshot of Ted Cruz for Senate is that winning candidates can wind up their campaigns’ outstanding financial obligations subject to vanishingly little oversight. Wealthy candidates who are able to finance their own campaigns will have an easier time buying elections, since they can be more confident in their ability to recover as much as they’re willing to lend.

At this point, it is hard to imagine this Supreme Court upholding any anticorruption law that Congress does not enact in response to a series of cash-stuffed briefcase swaps conducted in broad daylight and documented with receipts. Even then, at least three conservatives would write separately in defense of constitutional protections for the time-honored American tradition of rich people getting whatever they want.