The foreman of the jury that sentenced Wesley Ruiz to death called him “an animal,” a “mad dog,” a “thug,” and a “punk.” He was afraid of the Latinx people who came to Ruiz’s trial, he wrote in a sworn affidavit, because, given their tattoos, it was “obvious” that they were “gang members.” When one juror expressed tearful reservations about sentencing Ruiz to death, the foreman convinced her to change her mind, because Ruiz “could be dangerous.” Another juror who signed an affidavit attributed “demographic” changes in her Dallas neighborhood to “integration” and “bussing”—dog whistles for recent increases in Latinx residents. (Ruiz was from West Dallas, which she said was “even worse.”)

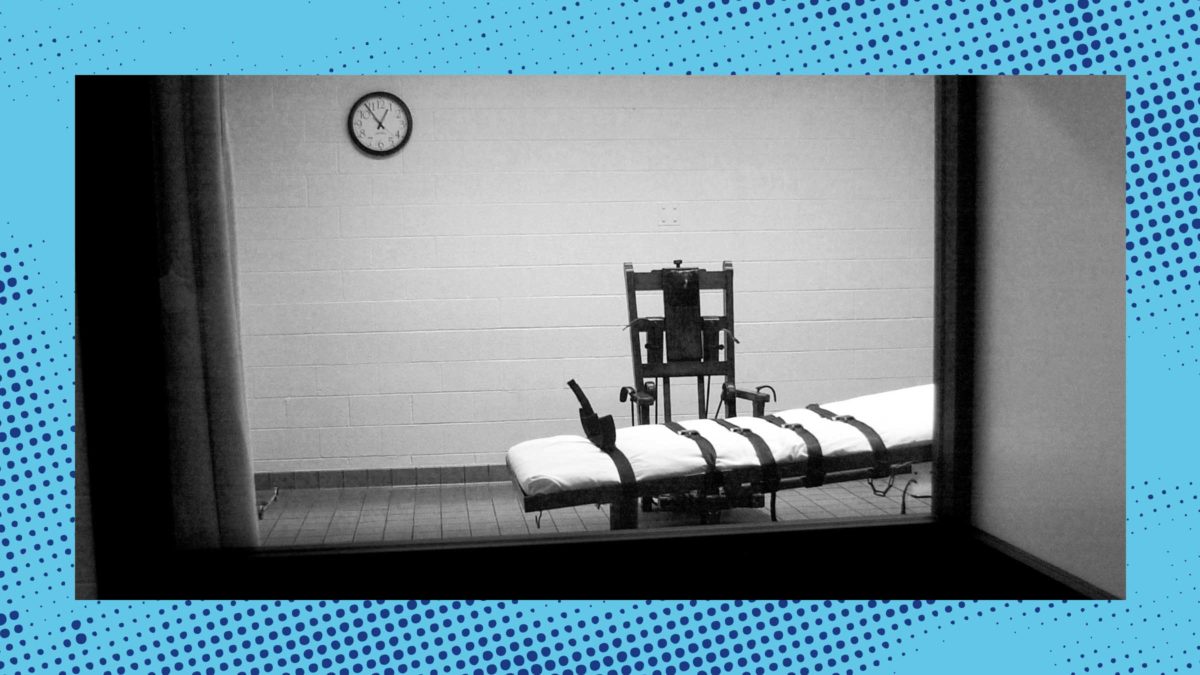

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that this kind of racial bias violates the Sixth Amendment right to an impartial jury. But on February 1, the justices refused to stop Ruiz’s execution in a brief unsigned order. The state of Texas executed Ruiz later that night.

NEW: The Supreme Court declines to block the execution of Wesley Ruiz, scheduled to take place this evening in Texas. Ruiz argued that jurors relied on anti-Hispanic stereotypes in deciding to sentence him to death. With no recorded dissents, SCOTUS denies his request for a stay. pic.twitter.com/TSchL2BsI8

— SCOTUSblog (@SCOTUSblog) February 1, 2023

On March 21, 2007, Dallas police were on the lookout for a 1996 Chevy Caprice linked to a murder suspect. It was Ruiz’s bad luck that he was driving a (different) 1996 Chevy Caprice when Officer Mark Nix tried to get him to pull over. Instead, Ruiz accelerated—he later testified that he fled because he had drugs in the car—which began a car chase between him and Nix. Ruiz made a turn too fast, hit a curb, and lost control of the Caprice, crashing. Nix and another officer’s car blocked Ruiz in. Nix ran to the front passenger window and began smashing it with his baton; according to Ruiz, Nix threatened to kill him. Ruiz, fearing for his life, shot a single bullet through the rear passenger window, killing Nix.

Ruiz was charged with and convicted of murder. At his sentencing, the jury had to decide between life in prison without the possibility of parole or the death penalty based on how they perceived his propensity for “future dangerousness.” They opted for the death penalty. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed his sentence in 2011.

In 2017, however, the Supreme Court issued an opinion that should have been helpful for Ruiz: Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado, in which the justices held that when a jury relies on “racial stereotypes or animus to convict a criminal defendant,” the Sixth Amendment requires that courts “consider the evidence of the juror’s statement and any resulting denial of the jury trial guarantee.” Historically, jurors have been prohibited from testifying about jury room deliberations to encourage jurors to speak candidly behind closed doors. But the Court held in Peña-Rodriguez that courts should disregard that rule when it comes to evidence of racial bias.

In August 2022, Ruiz’s legal team tracked down the jury foreman and convinced him to sign an affidavit about his experience. (Ruiz’s previous lawyers were apparently less diligent; the foreman noted that they did not ask him “nearly as much” as the new lawyers did.) In January 2023, Ruiz appealed his death sentence in Texas state court on this basis. After the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied his request as an “abuse” of the appeals system, Ruiz appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. A linguistic anthropologist who analyzed the jurors’ affidavits on Ruiz’s behalf concluded that “there is no question that any decision by the jury that required an appraisal of this Hispanic defendant’s likelihood to commit acts of violence in the future was tainted by racism.”

In opposing Ruiz’s request, Texas claimed it had an “adequate and independent state procedural ground” to deny his claim, irrespective of Peña-Rodriguez: a state rule of evidence that restricts the number of appeals available to defendants. By prioritizing state evidence rules over the rights guaranteed by the Constitution, it’s almost as if Texas is declaring itself its own country again. And by allowing Texas to do so, the Supreme Court is tacitly endorsing this result.

Ruiz’s case is very similar to Cruz v. Arizona, in which the Court heard oral argument in November. In Cruz, Arizona state courts used the same “adequate and independent state procedural ground” argument to circumvent a Supreme Court ruling granting procedural protections to criminal defendants. Under a 1993 case, Simmons v. South Carolina, courts must inform juries considering the death penalty of any state laws that would affect the parole eligibility of a person sentenced to life in prison. But Arizona courts have refused to follow Simmons, citing a state law that only allows for new sentencing hearings if a substantial intervening change in the law took place. Both states are treating key Supreme Court cases as if they never happened.

Yesterday, the state of TX killed Wesley Ruiz despite new evidence jurors used overtly racist stereotypes while sentencing him to death, and amid ongoing controversy about the use of expired execution drugs. The death penalty is never justice. #NotInMyName https://t.co/Rl2jZ7pNry pic.twitter.com/mXasDq1cOS

— Southern Center for Human Rights (@southerncenter) February 2, 2023

In Cruz, LatinoJustice filed a friend-of-the-Court brief explaining how anti-Latinx bias pervades the “future dangerousness” analysis that juries undertake when deciding whether to impose the death penalty. The brief also pointed to studies that show that white people are more likely to associate Latinxs with criminality, particularly among white people who live near large populations of Latinxs. Another study of jury-eligible participants found that people surveyed strongly associated Latinxs with “danger” and white men with “safety.”

Cruz and Ruiz’s case aren’t one-off examples of Latinx bias. They are symptomatic of the difficulty Latinxs face in getting fair trials. The Supreme Court, in theory, has taken steps to address this. But as Wesley Ruiz’s case shows, when states are more dedicated to killing people than applying precedent, the Court is uninterested in doing much about it.