After the 2020 Census, South Carolina’s Republican-led legislature drew new electoral maps that excised over 30,000 Black voters from a Charleston-area district. The state’s chapter of the NAACP filed a lawsuit that prompted an eight-day trial with several expert witnesses and hundreds of exhibits entered into evidence. And last year, the trial court found that this “effective bleaching” of the Black voter population produced the precise demographic breakdown predicted to maintain Republican control over the district. The court further concluded that such a result would be “impossible” without racial gerrymandering.

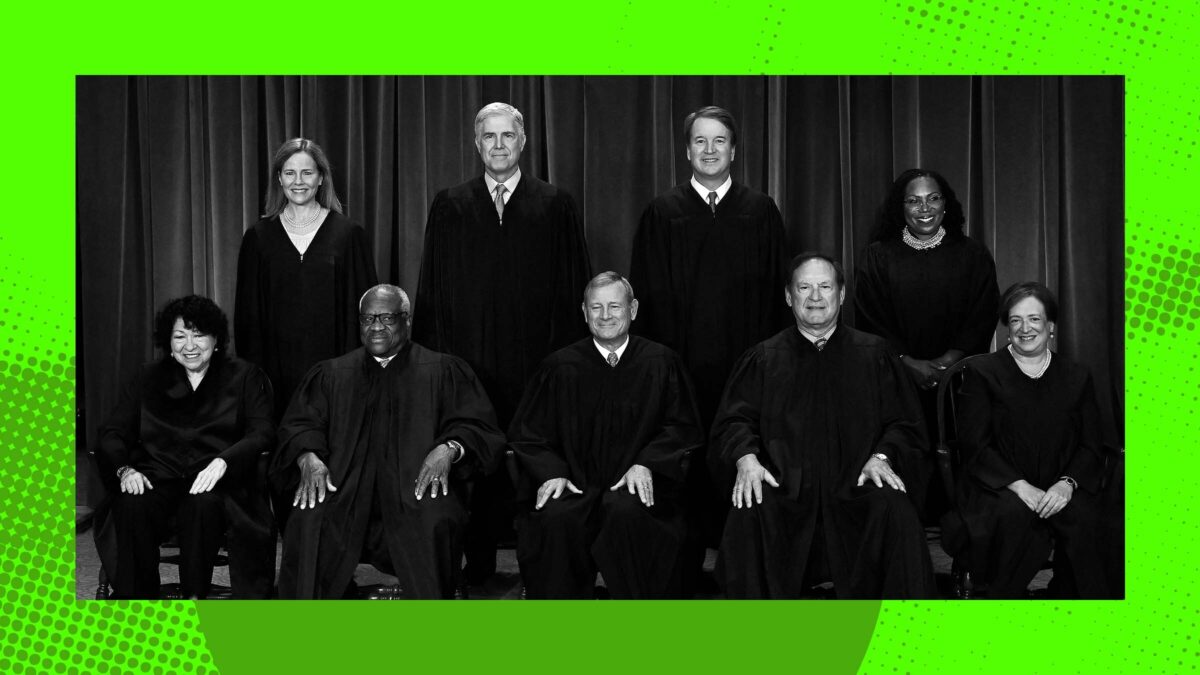

But none of that mattered to the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority, which overturned these findings about a week ago in Alexander v. South Carolina NAACP. Justice Samuel Alito, who authored the majority opinion in Alexander, explained that the maps did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s prohibition on racial discrimination because the maps were drawn for partisan reasons, not for racist reasons. He also insisted that legislatures are entitled to a “presumption of good faith,” and took great offense at the idea of besmirching the good name of states with spurious allegations of racism. Legislators are “bound by an oath to follow the Constitution,” Alito wrote, and courts must afford their judgments “due respect.”

Alito’s priorities are clear: He frames the possible injury to (white) legislators’ feelings as a grave harm, and is not at all concerned with the actual injury to Black people’s ability to freely and fairly participate in the political process. For him, it is also easier to believe that someone is lying about whether they experienced racism than to believe someone is lying about whether they did something racist. Alexander is the latest example of the Supreme Court’s perversion of the Fourteenth Amendment’s commitment to racial justice. In its place, the Court has constructed a jurisprudence of white fragility.

In Alexander, Alito further explained that striking down an electoral map as a racial gerrymander meant declaring that legislatures engaged in “offensive and demeaning conduct,” and he warned courts not to be “quick to hurl such accusations.” But the Reconstruction Amendments exist precisely because states regularly engaged (and engage) in such discriminatory conduct. The Amendments reflect the federal government’s conclusion that states could not be left to their own devices. Yet in Alito’s worldview, the Fourteenth Amendment’s history is irrelevant to understanding and enforcing it today.

Finally, wrote Alito, courts must presume legislators’ good faith because litigants might otherwise attempt to use gerrymandering lawsuits to secure “political” advantages. This completely discounted the trial court’s finding that the legislature used a racial target when drawing the district. It also ignores that voter suppression remains a problem, especially at the state level: More than 100 restrictive voting laws have been enacted across the country in the past decade, and the burdens of such laws fall disproportionately on people of color.

Alito’s analysis—that states should be trusted and people of color should not—is the exact inverse of what the Constitution commands. His presumption of good faith cannot be squared with the Reconstruction Amendments’ specific prohibition of discriminatory state action and grant of enforcement authority to the federal government. Nor can it be reconciled with the present realities of racism, which persist today in large part because the Court has spent most of its existence allowing the Reconstruction Amendments’ promises to lapse.

Revealingly, the Court’s reluctance to characterize an action as racial discrimination evaporates when white feelings are at issue. For example, in the Students for Fair Admissions cases, in which the Supreme Court outlawed affirmative action in colleges and universities, the majority frames efforts to provide students of color with long-denied educational opportunities as a penalty for being white. It warns that schools awarding a “plus” factor to applicants of color may “discriminate against those racial groups that were not the beneficiaries of the race-based preference,” and says the dissent’s suggestion that white and Asian students could also receive a diversity plus “blinks reality.” As Professor Khiara Bridges has observed, “the Court finds and remedies an alleged racial injury when white claimants feel like they have been injured on account of their race.”

The Court has gutted the Voting Rights Act using a similar rationale. In Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, the Court functionally struck down a provision of the law that required local governments with histories of voting discrimination to “pre-clear” changes to their voting policies with the federal government, in order to be sure that those changes did not discriminate. The Court explained its decision in Shelby County by claiming that preclearance violated the principle of “equal sovereignty” among the states, presenting it as an insult to states that were treated differently. Here, too, the insult to people of color is an afterthought at most.

Today’s conservative justices are so horrified by accusations of racism that they let actual racism slide. The Reconstruction Amendments were crafted to be powerful tools to counter societal injustice. But they are useless in the hands of a reactionary Supreme Court that is more interested in protecting white feelings than protecting all Americans’ rights.