Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in a pair of lawsuits concerning Texas’s most recent effort to ban abortion. The question was ostensibly a narrow one: Can Texas outlaw abortion by inventing a convoluted enforcement scheme that robs courts of their ability to do anything about it?

The cases deal with a Texas abortion law known as SB8, which prohibits most abortions after six weeks. The hijinks are baked into the law’s sinister enforcement scheme: Usually, lawsuits seeking to block an unconstitutional law are brought against the public official charged with enforcing it. But SB8 deputizes private citizens, not public officials, to do so, allowing them to sue anyone who “aids or abets” an illegal abortion and collect a cash prize for their troubles. This was not, as Justice Brett Kavanaugh pointed out at oral argument, an attempt to render the law constitutional, but an effort to exploit a “loophole” that would immunize it from challenge. No official, Texas argued, no lawsuit.

In the months since SB8’s passage, this bounty system has been characterized as a first-of-its-kind effort to evade judicial scrutiny; the three liberal justices referred to it as “wholly unprecedented.” But the law’s structure is a familiar one, torn from the playbook of Texas’s strenuous efforts to deprive citizens it disfavors of another foundational right: the right to vote. Even if the Court decides that Texas went too far this time, experience in the voting rights sphere suggests that lawmakers will find subtler ways to hollow out constitutional rights very soon.

Notorious among Texas’s early efforts to limit the franchise were so-called “white primaries.” In the early 20th century, Democratic candidates were virtually guaranteed to win general elections in Texas and throughout the South, meaning that the Democratic primary effectively determined the general election winner. In 1932, Texas Democrats repealed the state’s laws governing party membership. Weeks later, the Democratic Party adopted a resolution limiting its membership to “white citizens.” Suddenly, lawmakers had functionally barred Black voters from participating in democracy without ever having to say so.

Texas’s history suggests that lawmakers will keep trying to find new ways to make the state a Constitution-free zone. It may take another Roosevelt-style remake of the Supreme Court to stop it.

Like SB8, this Texas two-step was a cynical effort to short-circuit the usual legal process. The Constitution, remember, limits only government actions. By delegating the authority to set voting qualifications to parties, which are private entities, the state believed it could disqualify Black voters without facing constitutional consequences. In theory, the resulting disenfranchisement would be a product of the Democratic Party’s choices, not the state’s. Sound familiar?

At first, Texas’s scheme held: In 1935, a unanimous Supreme Court held in Grovey v. Townsend that white primaries did not violate the Constitution because they were not the product of state action. They primaries continued for nearly a decade until the NAACP, in a lawsuit brought by Thurgood Marshall, challenged the law again in Smith v. Allwright. This time, an overhauled Court that included seven new justices appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt overruled Grovey, recognizing that a state could not wash its hands of responsibility for enforcing the Fifteenth Amendment by simply outsourcing that task to political parties.

The decision in Allwright may have ended the most blatant of Texas’s attempts to outsource voter suppression, but these efforts persist in other, subtler forms. Today, for example, Texas maintains the strictest voter registration laws in the country, passed under the guise of preventing nonexistent voter fraud. These laws impose draconian rules on the voter registration drives that are so critical to boosting democratic participation, especially in minority communities: Black and Latino voters are twice as likely as white voters to register during voter registration drives than through other means.

At the center of Texas’s voter registration scheme is a program known as “Volunteer Deputy Registrars” (“VDRs”). Under state law, VDRs are the only private parties who can accept and deliver completed applications for processing, which means that registration drives are largely dependent upon their availability. But Texas heavily regulates who can be a VDR and who cannot: VDRs must be Texas citizens, complete certain training requirements, and obtain the approval of the county registrar in each county where they plan to work. VDRs are also subject to strict criminal penalties, including mandatory minimum jail sentences, if they make mistakes—a strong disincentive for would-be volunteers considering signing up for a weekend shift. This gatekeeping system has all but driven outside voter registration groups from Texas.

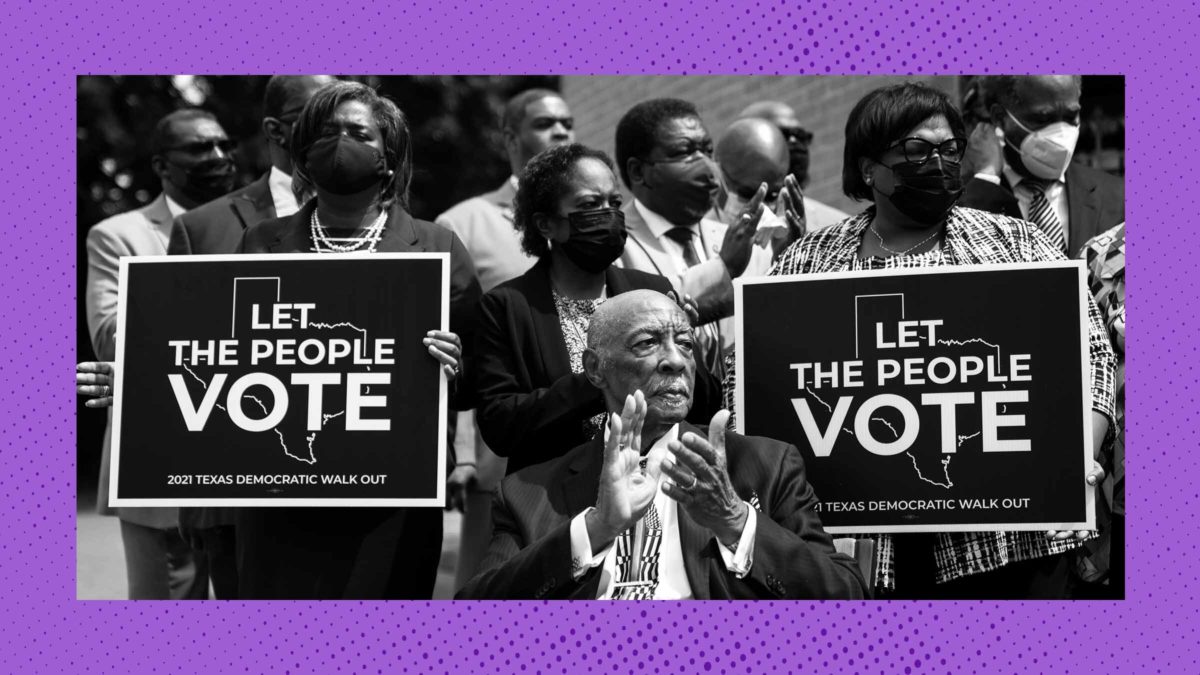

(Photo By Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call)

A decade ago, voting rights groups challenged the scheme as a violation of the National Voter Registration Act, which, as the name suggests, establishes federal standards for voter registration. Texas law prohibits photocopying of applications in the possession of VDRs, but as the groups pointed out, the NVRA requires states to permit photocopying of applications “‘maintained’ by the State.” (Photocopying is a standard practice that allows interest groups to get in touch with new voters and encourage them to turn out.) But the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals—the same ultraconservative court that embraced SB8—refused to apply the NVRA to VDRs, reasoning that the NVRA governs “states,” not private parties.

Similarly, although federal law requires states to accept mailed-in registration forms—another hallmark of successful registration drives—Texas prohibits VDRs from doing so. According to the Fifth Circuit, this is no problem, either: Although VDRs could be criminally punished for mailing completed registration forms, the court reasoned that the state could still accept them if any VDRs decided to risk jail time by sending them in. Once again, voting rights groups—and voters—were out of luck.

These efforts, spearheaded by Texas lawmakers and rubber-stamped by the Fifth Circuit, have had their desired effect. Texas’s voter registration rate ranked 44th in the nation in 2016, and the state came in 47th in turnout. The state’s registration rate had improved somewhat by 2020, but turnout did not. The burdens of this system fall disproportionately on voters of color. In the 2016 election, turnout among white voters exceeded Hispanic turnout by more than 20 percent, and Black turnout by more five percent.

For Texas, SB8 is a new move in an old game, chipping away at the rights of members of marginalized communities by attempting to disclaim responsibility for enforcing those rights. Whatever the Court decides about SB8’s fate, Texas’s history suggests that lawmakers will keep trying to find new ways to make the state a Constitution-free zone. It may take another Roosevelt-style remake of the Supreme Court to stop it.