In December 2024, when the Supreme Court heard oral argument in United States v. Skrmetti, Justice Amy Coney Barrett claimed to have no knowledge about how the government treats trans people. “At least as far as I can think of, we don’t have a history of de jure discrimination against transgender people, right?” she asked. “Is there a history that I don’t know about?”

Her skepticism had legal significance. Skrmetti was a constitutional challenge to a Tennessee law that denies gender-affirming care to trans children, and the Fourteenth Amendment commands that states shall not deny any person “equal protection of the laws.” If a state’s law targets a particular group, courts are generally supposed to ask why—and if there’s a history of discrimination against that group, courts may take a harder look at the state’s answers.

In June 2025, the Supreme Court upheld the Tennessee ban on a party-line vote. The majority opinion, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, skirted the question as to whether transgender people warrant heightened scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause by concluding that the law didn’t turn on transgender status at all, but on age and medical use of the treatment.

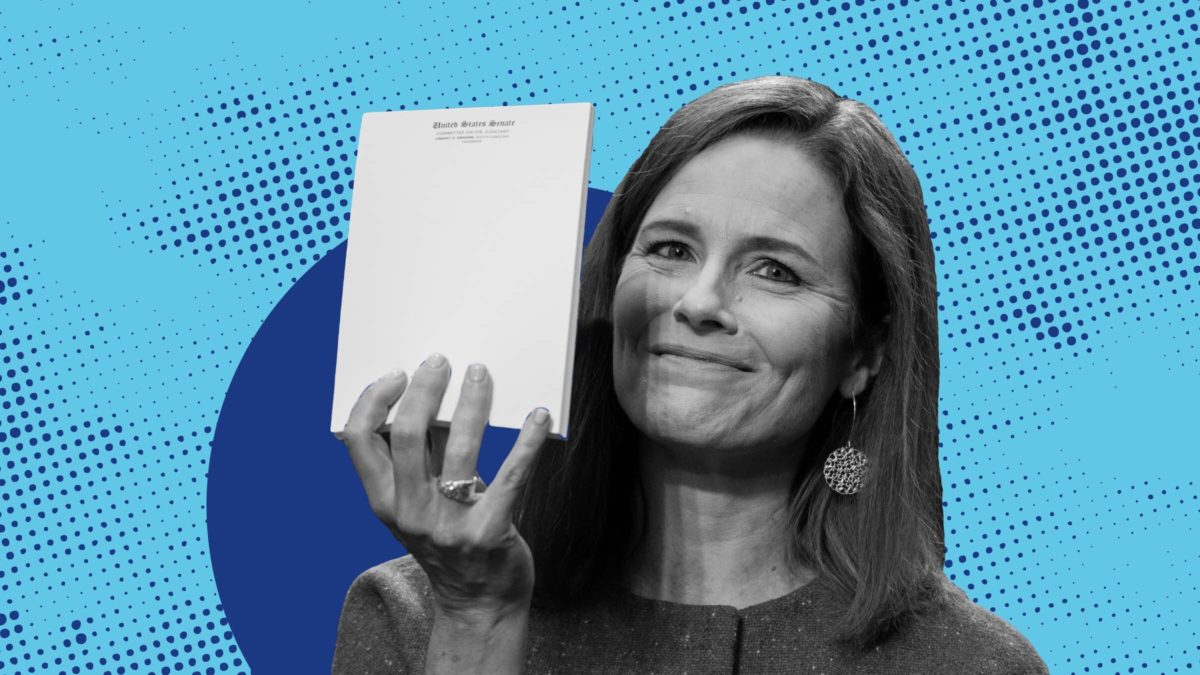

Yet in a concurrence, Barrett provided her answer anyway, sidestepping the Fourteenth Amendment’s requirements by embracing ignorance about the history of government-approved discrimination against transgender people. “The evidence that is before this Court is sparse but suggestive of relatively little de jure discrimination,” she said in an opinion joined by Justice Clarence Thomas. “Absent a demonstrated history of de jure discrimination,” she said, she “would not recognize a new suspect class” in future cases.

A group of experts on the history of LGBTQ rights are now trying to take that excuse away. On Tuesday, the Court will hear oral argument in West Virginia v. BPJ and Little v. Hecox, two cases challenging state laws that ban trans women and girls from playing school sports on teams that match their gender identity. Ten scholars filed an amicus brief in the cases that reveals the bans as a new chapter in an old story of government attacks on the rights of trans people.

“Transgender people have been subject to criminal prosecutions, forced institutionalization, and high-risk incarceration for nearly two centuries,” they write. For example, beginning in the 1800s, laws across the country made it a crime to wear gender non-conforming clothes. Oftentimes, law enforcement made trans people strip and subjected them to physical examinations to “prove” they were “cross-dressing.” Prosecutions under such laws continued well into the 20th century.

States also targeted trans people under “public decency” laws, which provided police with broad discretion to arrest “people who violated gender norms.” And routinely, police profiled and arrested trans people under suspicion of prostitution. One woman quoted in the brief recounted that, in 2008, police officers grabbed and handcuffed her while she was buying tacos. “They found condoms in my bra and said I was doing sex work,” she said. The brief notes that “the frequency of such police encounters has led to the transgender community naming the phenomenon ‘walking while trans.’”

People who exist while trans in America have risked detention not only in correctional institutions, but in mental institutions to which courts often confined them on a mandatory basis. Between 1937 and 1967, 26 states and Washington, D.C. passed laws that permitted indefinite detention of trans people. In 1955, under one of these statutes, Perfecto Martinez was deemed a “sexual psychopath” and “indefinitely committed to a psychiatric institution until cured for wearing women’s clothing and engaging in homosexual acts.”

The scholars further argue that trans people have faced historical exclusion and discrimination across many legal and societal institutions. Beginning in the late 1800s, for instance, the federal government had a policy of deporting transgender migrants, or blocking them from entering the country in the first place. A manual for immigration officials in 1918 warned that if “characteristics of one sex approach[ed] those of the other,” it was a potential sign of “degeneration.”

In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower issued an executive order barring trans people from federal employment on the grounds of “sexual perversion.” In 2025, President Donald Trump issued a similar executive order banning trans people from military service, declaring that “adoption of a gender identity inconsistent with an individual’s sex conflicts with a soldier’s commitment to an honorable, truthful, and disciplined lifestyle.”

The history of anti-trans discrimination in this country is not just history. It is present. And it is on the rise. In 2021, state legislatures considered 153 anti-trans bills, and passed 18 of them into law. In 2025, state legislatures considered 1,020 anti-trans bills, and passed 125. The scholars’ brief shows the link between a dark past that Barrett can no longer plausibly deny, and a darkening future that she and her conservative colleagues are helping to create.