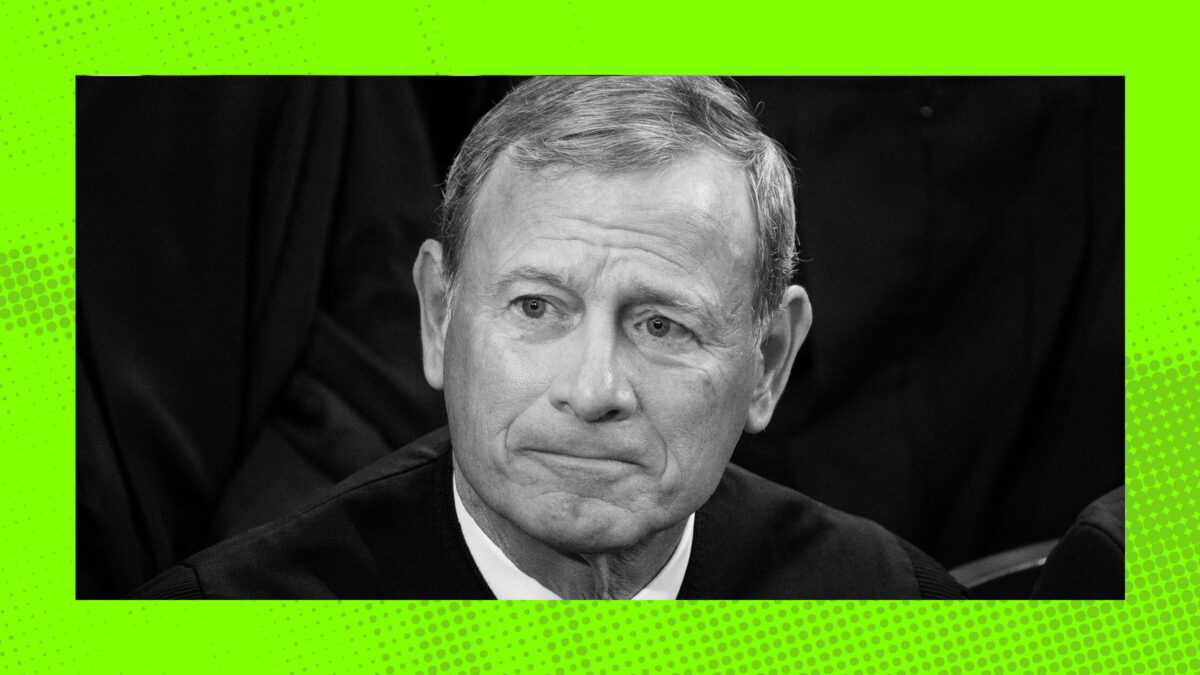

Last spring, after Politico published a draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that previewed the end of the right to abortion care, a wounded Chief Justice John Roberts excoriated the leak as a “betrayal” of the Supreme Court’s confidence. Praising the Court’s “intensely loyal” staff of career employees and law clerks, he promised a thorough investigation to identify (and presumably punish) the anonymous dissident.

“Court employees have an exemplary and important tradition of respecting the confidentiality of the judicial process and upholding the trust of the Court,” Roberts said in a statement. “This was a singular and egregious breach of that trust that is an affront to the Court and the community of public servants who work here.”

A handful of recent news stories, however, suggest that the Court’s workplace culture is perhaps not quite as tight-knit as Roberts imagines. On January 19, two days after the Court announced that it had been “unable to identify a person responsible” for the leak, The New York Times’s Jodi Kantor published a lengthy behind-the-scenes report on how the investigation had “further tainted the atmosphere inside a court that had already grown tense with disagreement.” Kantor described her sources as “almost two dozen current and former employees, former law clerks, advisers to last year’s clerkship class, and others close to them.” In the aftermath of a fruitless inquiry that closely scrutinized Court employees while all but ignoring the justices, it seems that a good number of people who work in the building had something to say about it.

The Supreme Court Marshal is getting a ton of shit and lots of it is deserved, but also, her office just isn’t qualified to do an investigation like this. The actual embarrassment here is, as usual, John Roberts. Layers of pathetic all the way down. https://t.co/UhcWi2stHr pic.twitter.com/neLUrPYfkb

— Jay Willis (@jaywillis) January 21, 2023

Subsequent stories about the Court’s internal goings-on were similarly unflattering. On January 27, CNN’s Joan Biskupic reported that the Court had not disclosed its history of engagements with former Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, a security consultant whom the Court touted as an “independent” reviewer of its leak investigation. (Chertoff, per “sources familiar with the arrangements,” had previously been paid upwards of $1 million to conduct risk assessments for the Court.) On February 9, there was yet another leak in The Washington Post, which reported that the justices had engaged in a years-long “internal discussion” about adopting a code of ethics, but had yet to come to a consensus behind closed doors. This story is particularly intriguing, because the topic suggests that the tipster (or tipsters!) sits somewhere near the tippy-top of the Supreme Court’s org chart.

Sourcing from within the Supreme Court isn’t new. Tell-all books about the Court typically rely on background conversations with justices and Court personnel with whom the writers have developed relationships. For The Brethren, their famous exposé of Chief Justice Warren Burger’s cartoonish incompetence, Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong conducted “interviews with more than two hundred people, including several Justices, more than 170 former law clerks, and several dozen former employees of the Court,” and gathered “thousands of pages” of unpublished internal memoranda, diaries, and draft opinions. Next to the years’ worth of documents that Woodward and Armstrong collected, a pair of Politico reporters hitting PUBLISH on a single PDF file seems almost quaint.

What’s different now, though, is that sources are offering specific details about timely news stories that, at a moment when the Court is embroiled in a legitimacy crisis of its own creation, manage to make the Court look even worse than it already does. For the Court to function, the people at the top have to foster a culture of mutual respect—not just among themselves, but among everyone in the building, from clerks to administrative assistants to cafeteria employees to cleaning workers. Staffers know they could lose their jobs for talking to the press, and clerks know that their prize for a year of drafting opinions and staying out of trouble is a partner-track law firm gig and a six-figure bonus. Financially speaking, ignoring reporters’ cold calls and Signal messages is the safest course of action for everyone involved.

These breaches of the Court’s tradition of quasi-omerta suggest that the justices have lost control, to the extent they ever had it in the first place. As high as the stakes are for themselves and their families and their careers, enough People Who Know Things have concluded that in an era of a conservative supermajority willing to do anything for which it has the votes, the cost of obedient silence is even higher. The picture that emerges is not of a Court characterized by thoughtful debate between nonpartisan jurists who, despite their occasional disagreements, nonetheless share a principled commitment to upholding the proverbial rule of law. It is of a Court that is coming apart at the seams.

Predictably, the initial handwringing over the Dobbs leak got the problem exactly backwards: Leaks are symptoms of eroding public trust in the Court, not causes of it. Increases in the number and frequency of leaks suggest that the public has more, not fewer, reasons to worry about whatever nightmarish shit might be coming next. The Court’s non-life-tenured employees can’t literally stop the next Dobbs or Brnovich or Bruen from happening. But they have found small ways to help expose the Court for what it is: a broken institution that is constitutionally incapable of fixing itself, and blithely uninterested in trying.