In the three years since Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s warp-speed confirmation yielded the most conservative Supreme Court majority in a century, the six justices who comprise it have been Federalist Society bulls in a civil rights china shop. They scrapped the right to abortion care after 50 years of trying, supercharged the proliferation of guns in a country racked by gun violence, and repurposed the First Amendment to protect the hurt feelings of rank bigots and/or conservative Christians. They further insulated voter suppression laws from meaningful scrutiny, even as Republican politicians work harder than ever to make it difficult for their constituents to vote. In June, they finally ended affirmative action in colleges and universities, striking a courageous blow on behalf of every mediocre rich white kid whose reach school rejected them even after daddy donated a new library.

To protect these and all future exercises in judicial policymaking from the democratically accountable parts of government, the Court scrambled the balance of power among the three branches, inventing for itself the authority to rewrite acts of Congress and roll back exercises of executive power with which the justices personally disagree. Going forward, anything and everything the government attempts to make the country marginally less worse will have the threat of Sam Alito’s veto looming over it in perpetuity. I could make this recap of Just How Bad Things Have Gotten much longer, but trust that you get the idea.

Conservative activists, on and off the bench, are more emboldened than ever. Some of the highest-profile cases of the Court’s upcoming term, which begins Monday, bubbled up out of the Fifth Circuit, the federal appeals court where judges actually or spiritually appointed by President Donald Trump have also spent the past few years going—sorry for the legal jargon here—absolutely fucking hog wild. How the Court handles these cases could have devastating consequences for millions of Americans: By July, the justices will decide whether the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is indeed unconstitutional, and whether “armed domestic abusers shooting and killing their partners” is a problem that lawmakers are powerless to solve. After solemnly swearing in Dobbs that the Court was merely promoting democracy by returning abortion to the states, they could also rule on whether a single Republican judge in Texas has the authority to ban medication abortion nationwide.

Among Supreme Court observers, the emerging consensus is that this is probably too much crazy, too fast—that the justices will rein in their aspiring colleagues on the Fifth Circuit, in at least some cases and to at least some extent. I think this is right, although I would not bet a single blessed thing on it. At the same time, an ostensibly quieter 2023-24 term would not necessarily be any less awful than the two that preceded it, because the cases the Court decides are only one aspect of how the institution exercises its tremendous power to inflict harm on things you care about. The Court works a little like gravity: It is always pulling the entire legal system in the direction the justices want to go, even if you can’t see it at work.

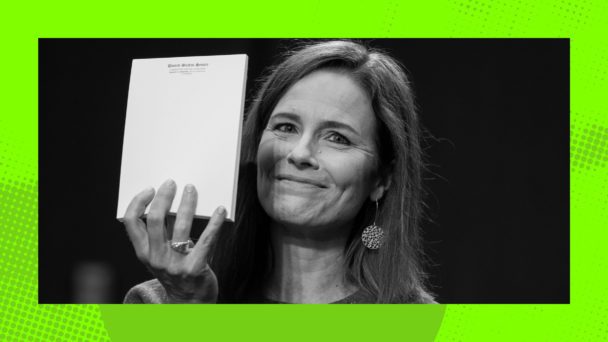

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Earlier this year, Senator Minority Leader Mitch McConnell wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post defending the conservative justices against charges of partisanship, capture, and/or graft, only some of which Mitch McConnell is personally responsible for. The Court, he wrote, is an “ideologically unpredictable body that takes cases as they come.”

Even by McConnell’s standards, this is an ambitious lie. As the law professor Steve Vladeck documents in his book The Shadow Docket, the justices spent decades lobbying for the right to choose how much work they do, and Congress has largely acquiesced, passing a series of laws relieving the Court of its duties to hear certain types of cases. Today’s Court enjoys near-total control over its docket, which is also shrinking at an alarming rate. In the mid-1990s, it wasn’t uncommon for the Court to hear oral argument in 100+ cases in a term. Last term, it heard 58, and as Vladeck observed, it has scheduled seven cases for oral argument over the first twelve slots this fall. The Court does not take cases “as they come”; it takes only the cases it wants to hear, and stuffs the rest in the garbage.

This is not to suggest that justices have an equal say in the process. Five votes are necessary to win a case, but only four are necessary to put it on the calendar. In an era of a conservative supermajority, this difference matters, because that supermajority can endure two defections and still get all the cases it wants. As a result, reactionaries have a near-total monopoly on the Court’s time, and there is basically no room for cases that could push the law to the left, even if a majority for some reason wanted to do so. In almost every opinion the Court hands down, the best-case scenario for conservatives is a grand reimagining of the law in the graven image of John Birch. For liberals, it’s a tepid (and perhaps fragile) affirmation of the status quo, over a furious Clarence Thomas dissent that doubles as a helpful roadmap for how Alliance Defending Freedom lawyers can structure the next vehicle to get a different result.

Finally, the Court’s ideological composition affects not only the cases it chooses, but the menu of cases from which it can choose in the first place. For liberal lawyers, there is precious little incentive to ask this Court to hear your case, since the likeliest outcome is a 6-3 shellacking that will take a generation to overturn if you’re lucky, and several generations if you’re not. For conservative lawyers, there is basically no cost to doing so. This means that every year, the country’s highest court is filling up its tiny calendar with the looniest cases plucked from an array of already-deranged asks. Even if the justices spend this term putting out the Fifth Circuit’s hottest, dumbest fires, this time next year, we could be talking once again about which fundamental rights won’t exist by the time you watch Fourth of July fireworks.

Sometimes, the most impactful entries on the Court’s docket are the least interesting to talk about. For all the attention paid to the Fifth Circuit’s various tire fires, the term’s biggest case is probably Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, in which the justices will consider getting rid of Chevron deference once and for all. Under this principle, named for a 1984 Supreme Court case, courts hearing legal challenges to a federal agency’s interpretations of its authority are supposed to defer to the agency, as long as that interpretation is reasonable. The idea is pretty simple: Agency experts are better equipped to make technical decisions about, say, how to carry out the mandates of the Clean Air Act than septuagenarian lawyers who double-majored in English and Classics during the Johnson administration.

The end of Chevron deference, for which conservative legal movement luminaries have long pushed, is at the center of the Court’s project of siphoning power from the democratically accountable branches. It would make unelected Republican judges even more unhinged than they already are; if you want robed homophobic bloggers instead of actual scientists to determine how much poison industrial chemical manufacturers can dump in your drinking water without facing legal consequences, you may soon get your wish.

When it’s time for a fishing trip (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Because conservatives worship at the altar of originalism only when doing so is politically expedient, I usually don’t care much for appeals to What The Framers Would Have Wanted. That said, it is hard to overstate how alarmed the Framers who’d just escaped a tyrannical, out-of-touch, unaccountable monarchy would be if they’d known that every year, we’d be waiting on pins and needles for nine life-tenured god-emperors to issue the final, unimpeachable word on what the law is. Loper Bright, which disguises the right-wing passion for deregulation as the output of correct legal reasoning, is as much a part of this tradition as any fight about guns or abortion or affirmative action or voting. It might not sound like a culture war case, but it could enable future Supreme Courts to win more culture wars that fewer people even notice.

Not every Supreme Court term will feel as bad as the worst Supreme Court term. But when the conservative justices have this much control over the agenda, for anyone who cares about civil rights or multiracial democracy or a functioning government, there is no such thing as winning a Supreme Court term, either. There is only losing a little more slowly.